In May 2019, Pragya Thakur, BJP MP in Bhopal, invoked the wrath of the nation when she termed Nathuram Godse, Mahatma Gandhi’s assassin, a ‘patriot’. Undeterred, she repeated herself in November.

Politicians and the public banded together in nationwide protests, calling for Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah to expel her from the party.

In May, Modi condemned her comments as "unacceptable", saying he would never forgive her.

In November, she was removed from a Parliamentary panel on defence, and can no longer attend BJP parliamentary party meetings during the current session; sources claim she will soon be expelled from the party.

While Thakur’s crude, irrational eulogization of a murderer merits criticism and crassly ignores the contributions of one of India’s founding fathers, the ensuing reaction is part of a larger nationwide reluctance to accept even valid criticisms of Gandhi.

He graces each of the country’s bills, is the face of multiple government campaigns and initiatives, and is even worshipped as a god in temples in Telangana and Orissa.

Even ignoring why he continues to be disproportionately glorified compared to others like Subhash Chandra Bose, Chandra Shekhar Azad, and Bhagat Singh, the question remains: why is criticism of Gandhi so off-limits?

Earlier this year, following the vandalization of a Gandhi statue in Jalaun, Uttar Pradesh, protestors and politicians like Priyanka Gandhi indicated that those who don’t agree with Gandhi or his ideology are 'cowards'.

While such public misdemeanours require punishment, the intensity of the reactions threatens to set a legal precedent for disproportionate retribution.

For example, in 2015, the Supreme Court refused to remove criminal proceedings against a publisher for his poem about Gandhi. It warned that “freedom of speech and expression is not absolute” when it comes to ‘iconic’ historical figures. In fact, it said that such actions risk being charged under Section 292 of Indian Penal Code, which carries a jail term of two years.

Yet, this is a man who said that part of India’s struggle was forcing the Europeans to see that Indians were being “degraded” by being treated the same as Black Africans. He argued that Indians were “infinitely superior” to the Africans, who he said were merely hunters whose “sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass [their] life in indolence and nakedness”.

This is a man who forced his 18-year-old grand-niece to sleep beside him in the nude so as to test his chastity and strength of resolve. He told her it was of national importance, as his ability to resist sexual temptations would assure him of his single-mindedness in achieving Indian independence.

India is not alone in its reluctance to accept criticism of revered historical figures, though.

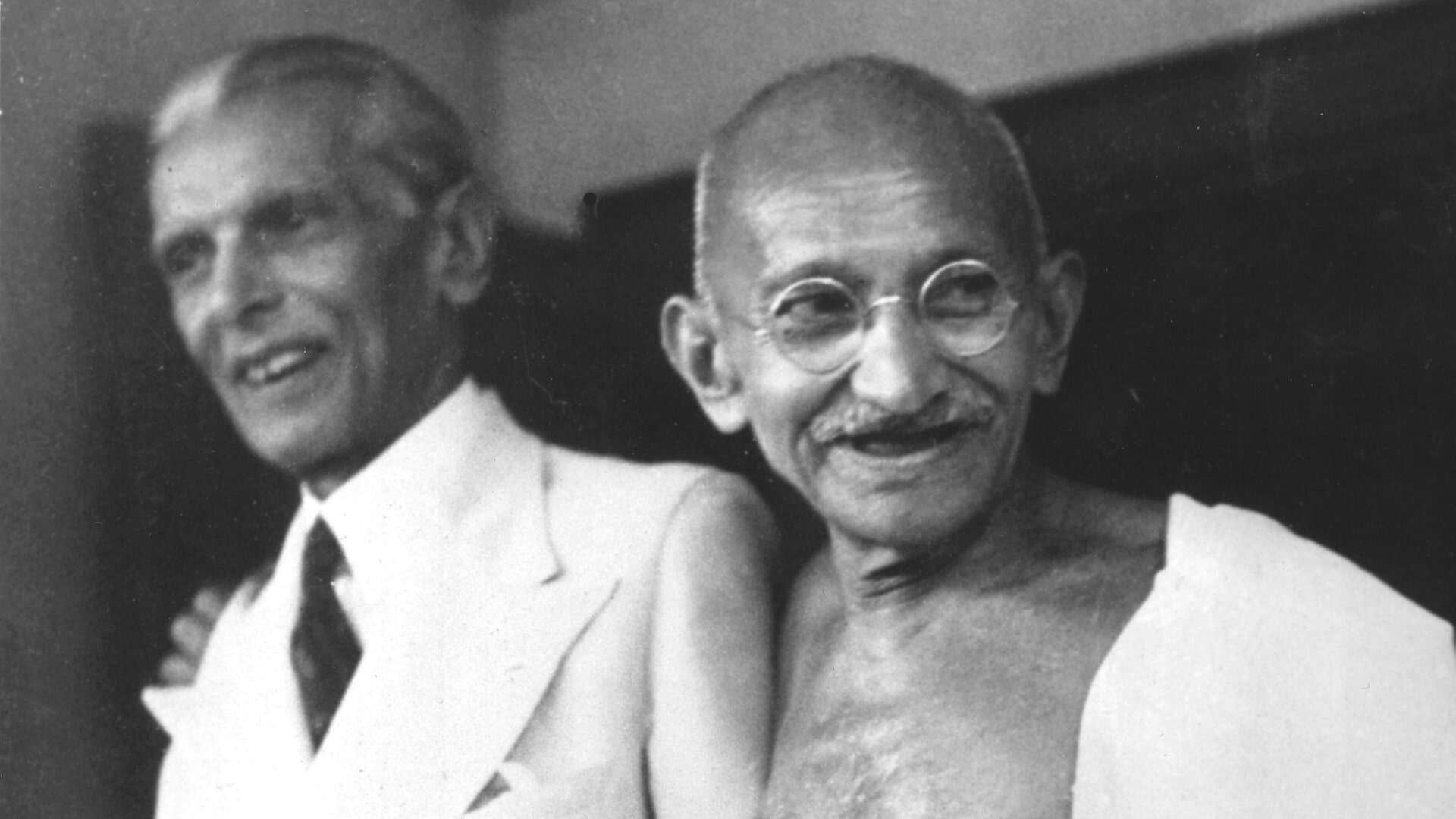

Muhammad Ali Jinnah is celebrated as Pakistan’s Quaid-e-Azam, or great leader, and he is a part of every school's curriculum. Portraits of him hang in every "school, military mess, and office", and towns and streets are named after him. He is portrayed as a strict Muslim who fought tirelessly for the creation of Pakistan.

Criticism of Jinnah is considered blasphemous. For instance, in 1999, protests erupted over the release of a movie showing Jinnah "crying” over those killed in the partition. They argued that this “Hindu and Zionist” plot was an ‘un-Islamic’, ‘un-Pakistani’ portrayal that suggested that Jinnah was by extension crying about the formation of Pakistan.

Yet, according to Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal, Jinnah did not even want a completely independent Pakistan; rather, he wanted one federal polity with two 'autonomous entities’– Hindustan and Pakistan. In fact, he even wanted the accession of some Hindu majority states to Pakistan. Ultimately, though, partition resulted in two separate, centralized countries. Moreover, in stark contrast to his depiction as a staunch Muslim, according to multiple reports, Jinnah was a chain smoker, drank alcohol regularly, and even ate ham sandwiches and pork sausages.

Similarly, Winston Churchill, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, is portrayed as a heroic, inspirational leader. Criticism of Churchill is met with swift and stern reprisal. For example, in February, shadow chancellor John McDonell's description of Churchill as a "villain” drew the ire of both sides of the aisle. Current Prime Minister Boris Johnson demanded that McDonell withdraw his comment, while Labour MP Ian Austin reiterated that Churchill is the “greatest ever Briton”.

Yet, this great Briton murdered Pashtun tribesmen in Afghanistan to teach them “the superiority of the British race” in 1897; suggested bombing Irish protestors in 1920; proposed using chemical weapons against the Kurds and Indians; forced 150,000 Kenyans into concentration camps to make way for white colonialists; ordered the diversion of food supplies from “beastly” Indians that resulted in the death of 4 million in the 1943 Bengal Famine; described his role in British-run concentration camps during the Boer Wars as “great fun”; referred to Palestinians as "barbaric hordes who ate little but camel dung”; and proudly boasted of killing three “savages” in Sudan. In fact, his own secretary of state for India, Leopold Amery, said that he saw little difference between Churchill and Adolf Hitler.

Likewise, in the United States, while several statues and monuments of Confederate leaders have been taken down for glorifying proponents of slavery, structures like Mount Rushmore–built on stolen Sioux land–and the Washington Monument remain. Although he played a major role in the emancipation of slaves, George Washington purchased “dozens” of slaves, and wanted to “extirpate” any Native Americans who didn’t agree to sell their land to the US government. Thus, erecting monuments in his honour merely honours Washington’s guilty conscience.

The face of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara is printed on political propaganda and t-shirts worldwide. Yet, his firing squads and labour camps indiscriminately killed all those who stood in his way; Guevara said, “if in doubt, kill him”, “judicial proof is unnecessary” and that his revolution was a “cold killing machine motivated by pure hate”.

Albanian nun Mother Teresa was a Nobel Peace Prize-winning laureate, and is honoured in the Catholic Church and worldwide as a Saint for devoting her life to caring for the sick and poor in India. However, her aid was “so dangerously lacking it bordered on negligent”. Patients in her medical centres were treated in “squalid” conditions; workers reused needles; patients were purposely given insufficient doses of medicines to reduce ‘wastage’; nurses administered expired medicines; volunteers with little or no training operated on patients with highly contagious and life-threatening illnesses; and food in her soup kitchens was rarely replenished. All this despite millions of dollars in donations.

Fifteenth-century Italian sailor Christopher Columbus is hailed as the discoverer of the ‘New World’ in the Americas and is celebrated annually across North and South America, and in Spain and Italy. Even ignoring the fact that his arrival precipitated the brutal European colonization of indigenous lands and peoples, how could he have discovered the Americas when it was already populated? It wasn’t even the indigenous peoples’ first contact with Europeans, either. Viking settlements from the 11th century, 500 years before Columbus reached the Americas, have been found on the east coast of Canada.

Women’s suffragists are honoured for achieving women’s right to vote in the US in 1920, following a nearly century-long struggle. However, this right only extended to White women. In fact, the women’s suffragists actively campaigned against giving Black Americans the right to vote. In reality, Chinese women couldn't vote until 1943, Native American women couldn’t vote until 1948, and Black women couldn’t vote until 1965.

Criticism of venerated historical figures does not erase the fact that Gandhi and Jinnah contributed to India and Pakistan’s independence, respectively; that Churchill’s leadership influenced the Allied victory over the Nazis; or that the American women’s suffragists paved the way for universal suffrage in the US.

Noting their transgressions, however big or small, isn’t an erasure of history. It’s contextualization. It isn’t necessary for the records of historical figures to be blemish-free.

It has been suggested that one should not judge historical figures through the lens of today’s politics or moral codes. While people are indeed the products of their time, some ethics are universal and transcend time. For example, the moral reprehensibility of racism, colonialism, and greed are not modern concepts; they have been criticized across eras.

The excuse of ‘vertical relativism’, which states that ethical judgments should be informed by the cultural values and societal norms of their time, is simply a crutch to look at history through rose-tinted glasses.

Thus, to suggest that Gandhi’s racism and sexual depravity or Churchill’s global human rights abuses were because of the geopolitics and sociocultural frameworks of their time is willful ignorance.

Why then are they beyond reproach?