The Kashmir conflict is a very complex issue which began around the time of the Partition of India in 1947. Earlier this month, Articles 370 and 35A, which allowed Kashmir a separate Constitution and a special status under the Indian government, were scrapped by way of a Presidential Order, and the statehood of J&K was revoked. Rather, the region is now divided into two Union Territories — J&K and Ladakh. While this move by the BJP-led government has received resounding support from many of the country’s citizens, key members of the political Opposition, as well as the Russian administration, it has also received backlash by many with respect to the heavy militarization, arrests, curfews, and blockades that went into its execution. This has sparked several debates regarding territorialism, nationalism, democracy, identity, law, and religion all over the country, on which you can find multitudes of perspectives and reports in the news right now.

There are two major dimensions that surround the Kashmir conflict: the first is the internal one that deals with the socio-political and economic demands of the people from the Indian state of J&K. The second is the external dimension, which involves Pakistan and China and their claims over certain parts of J&K — Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (or ‘Azad Kashmir’) and Aksai Chin, respectively. Yet, New Delhi’s current stance — a very strong one at that — is that the issue is an ‘internal matter’ and not a bilateral one. Pakistan, who is obviously against India on their decision to revoke the Articles without any warning, tried moving the United Nations Security Council (UNSC, or SC) to discuss the resolution of this issue within a few days after this move was announced by Indian officials. China soon joined them in their appeal, and last week the UNSC held a closed-door special hearing on the subject with the two countries, without their presence in the meeting. In this article, I chart out a detailed history of UN involvement in Kashmir and discuss its dwindling relevance in the region today.

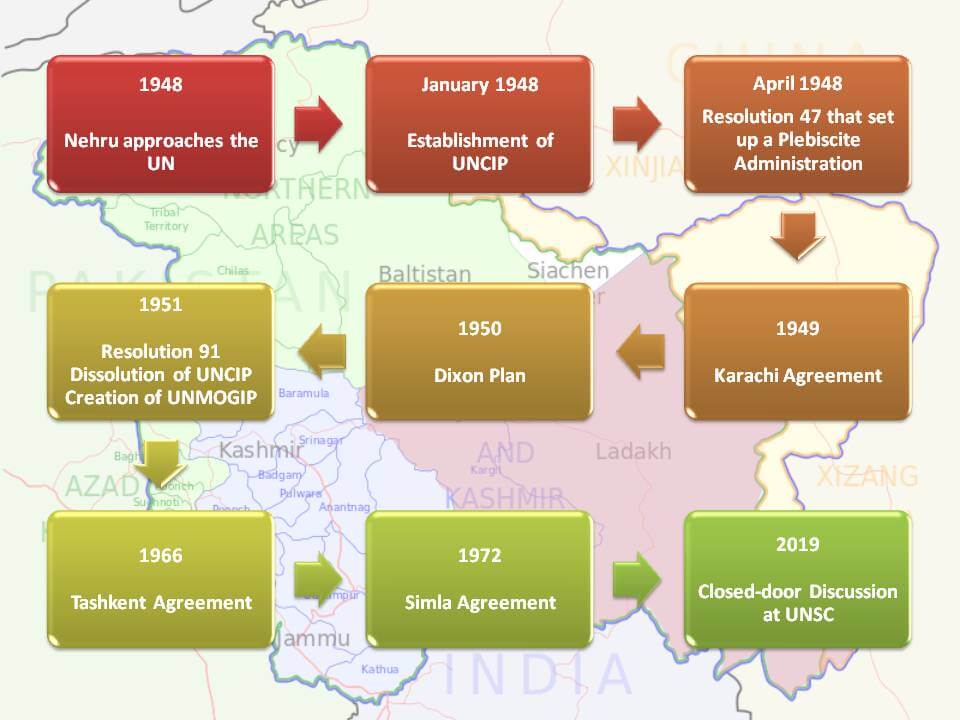

Image 1: A Timeline of Diplomatic Efforts with respect to Kashmir

After several failed attempts at negotiations between British mediators, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan with respect to a ceasefire or plebiscite agreement, a reluctant Nehru approached the UN to help resolve the matter in 1948. Under Article 35 of the UN Charter, any member state is allowed to bring a dispute which is likely to result in international disturbance to the notice of the SC. It is believed that Pakistan initially denied Indian claims that “Pakistani nationals and tribesmen” had caused violence in the state of J&K. Instead, Pakistan alleged that India had plotted a “genocide” of Muslims and had fraudulently engineered the accession of the State through aggression.

The UNSC, on 17 January 1948, decided to invite delegations of India and Pakistan to participate in direct talks. Three days later, they set up the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), which set out to investigate and mediate tensions between the two powers in the hotbed zone. According to Raghavan, the SC’s approach towards Kashmir was largely influenced by the British representatives led by Philip Noel-Baker, who believed that because Britain had already angered the Muslim world due to their stance on the Palestine-Israel issue, siding with India on this matter would further fuel the fire and further alienate the Arabs from the Western powers. Apart from this, Noel-Baker explicitly believed that due to the high density of Muslims in Kashmir, it rightfully belonged to Pakistan. As a result, Britain and its allies in the UNSC dismissed India’s complaint and stated that only a fair plebiscite would stop the hostility in the area.

Nehru was upset by this and stated that the US and the UK had “played a dirty role” in the SC. In the following months, Sheikh Abdullah who was then heading the administration of J&K and was against the notion of a two-nation plebiscite, proposed the idea of an independent Kashmir. Canada, a member state at the UN, also suggested that the referendum include a third option, but the proposition was quashed by the British as they were worried that a third option would add a new cause to the existing tensions between the two countries.

On April 21 of the same year, the UNSC passed Resolution 47, “noting with satisfaction that both India and Pakistan desire that the question of the accession of Jammu and Kashmir should be decided through the democratic method of a free and impartial plebiscite.” The Resolution Increased the number of member states in the UNCIP from three to five, and also gave instructions as to how peace can be restored in Kashmir. The Resolution called for the withdrawal of Pakistani nationals and tribesmen from Kashmir, and for India to scale down its military presence to a bare minimum and instruct their troops not to intimidate the local population. It also called for both countries to protect minorities, rehabilitate displaced persons, and release all political prisoners. Lastly and most importantly, the Resolution had provisions for the creation of a Plebiscite Administration that would impartially preside over the promised referendum vote.

It is crucial to note that Resolution 47 was not enforceable or binding on either party, as it was passed under Chapter VI of the UN Charter. Other resolutions that followed in the same year also laid out terms of ceasefire and truce. At this point, it was revealed by the Pakistani foreign minister that their troops were actually combating in Kashmir. By then, the resentful Indian administration decided that it was no longer going to compromise. The resolution then recognized that Pakistan had to be the first party to clear out, and India too would, in phases, scale back its military deployment once notified of Pakistan’s removal. After this truce, the countries were to consult with the UNCIP for a resolution of the issue via a referendum that would reflect the will of the people of Kashmir.

It is believed that this resolution was the first time the UNSC acknowledged Pakistan as an aggressor, which the country’s leaders felt was “tantamount to a rejection”. Yet, two of its recommendations were successfully taken into account — the ceasefire, and the deployment of unarmed military observers.

Ceasefire and the Karachi Agreement

The war finally ended in a ceasefire that came into effect in 1949, but the ceasefire line was drawn up only six months later, by way of the Karachi Agreement. This Agreement divided the area of Kashmir between the two countries, and sanctioned the stationing of military observers at the frontier who would supervise the ceasefire line. It was expected that the next decade would be spent with both countries working out a practical formula for the plebiscite as well as demilitarization. However, none of this happened; instead, both countries strengthened their military presence in their respective areas of control. In 1950, the UNSC appointed an Australian judge, Sir Owen Dixon, as the representative to India and Pakistan. His report, known as the Dixon Plan, assigned PoK and the Northern areas of Kashmir to Pakistan, Ladakh to India, and split Jammu between the two in a bid for a plebiscite recommendation in the Valley. The Plan also noted that neither party was willing to adhere to the preconditions set out for the process of demilitarization or a plebiscite. As war was seeming more and more imminent, diplomatic efforts by the UN grew more intense.

In March 1951, the UNSC adopted Resolution 91, which called for arbitration if demilitarization efforts were not carried out within three months. It also dissolved the UNCIP to make way for the UN Military Observers Group for India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP), and officially accounted for the new constituent assembly of J&K which was elected earlier in the year. India rejected this resolution, so the UNMOGIP was only able to investigate the allegations of ceasefire violations and submit subsequent reports to the UN Secretary General or to either country.

A. G. Noorani states that the Dixon Plan was the only solution that seemed to meet Delhi’s approval. Dixon’s successors, Frank Graham and Gunnar Jarring, have been criticized for their incompetence and escapism respectively. In 1956, J&K’s assembly voted for accession to India, and as the decade went on, Pakistan took on the role of the chief advocate for plebiscite, while India grew further away from that idea.

From Tashkent to Simla and Beyond

By 1965, fresh battles broke out in the region, and the subsequent UN resolutions on the “India-Pakistan Question” became more plaintive than detailed. That year, the UNSC passed three resolutions that pleaded to the two powers to cooperate with their military observers, and for them to end the conflict. Resolution 211 called for an unconditional ceasefire, which both parties agreed to. The famed Tashkent Agreement was signed in accordance with this in 1966 with joint support from the UN, the USA, and the Soviet Union. The Agreement stated that India and Pakistan would both have to surrender their conquered territories and go back to the ceasefire line established in the Karachi Agreement.

This absence of war only lasted until the 1971 Bangladesh War, when Pakistani and Indian troops were engaged in combat on both, the Eastern and Western fronts. The Pakistani Army had already surrendered in the East, and India declared a unilateral ceasefire on the Western frontier before the UNSC could pass Resolution 307 on 21 December. The resolution repeated again that both armies must retreat to the previously decided ceasefire line.

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Pakistan President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, on 2 July 1972, signed the Simla Agreement as a guiding force to solve the Kashmir issue. The Simla Agreement followed a similar course as the Karachi Agreement, spare for a few changes. It also stated that “the two countries are resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations or by any other peaceful means mutually agreed upon between them”. The most significant contribution of the Simla Agreement was the renaming of the ceasefire line to the Line of Control. Later, it seems that both countries met again to decide that the LoC would be considered an international border between them. India believed that the formation of the LoC rendered the UNMOGIP as insignificant since its primary purpose was to monitor the ceasefire line. Pakistan, however, did not agree, and their military authorities continue to register complaints of ceasefire violations to the UNMOGIP.

The Simla Agreement was extremely significant for the reason that it finally got the countries to agree to solve the issue bilaterally. In the years to follow, Pakistan began establishing its presence in the Islamic world to fulfil its foreign policy goals, and further entrenched the territorial status quo by refusing to give an independent status for Azad Kashmir in 1973. The Northern areas of J&K and Azad Kashmir were waiting for a plebiscite, but the Indian case for “accession” ruined any chances of Pakistan adhering to the conditions of the referendum. In this context, the legal aspect of the Kashmir issue seems a lot more daunting than its political problems.

What Now?

The UN’s existence in Kashmir has moved steadily into the background, as its relevance as an international peacekeeping body fades away. For years, their military observers’ office lay abandoned in Srinagar’s political district. This presence was rekindled on 16 August 2019 for the first time since 1971, when the UNSC held a “closed-door” meeting requested by Pakistan and its ally China, to discuss the developments in Kashmir after the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A by the Indian government.

The UNSC has not yet declared an official statement about the meeting held, but it has been reported that the Council declared the issue to be a bilateral one and "urged" both countries to exercise restraint, similar to India’s position in UN discussions on Kashmir previously. After the meeting, Indian representatives staunchly persisted that issues regarding J&K are internal matters of the State, accusing its neighbours of “misleading the world”. Syed Akbaruddin, India’s Ambassador to the UN, pointed his finger at the leaders of Pakistan and China for imparting too much significance to the meeting and attempting to make the matter an international one. Indian media has reported on the outcome of the meeting as being a public humiliation of Pakistan and China in the international system.

As of now, Pakistan has suspended all bilateral relations with India, and the latter has refused to enter discussions until the former end their alleged state-sponsored terrorism in the area. The UN’s reluctance to release a press statement regarding the meeting has been taken as a snub to Pakistan and China, while India maintains its position of the issue being an internal one. Reiterating a resolution from decades ago, referring to the Simla Agreement, and reinforcing the idea in the international system that the issue is a bilateral one seem to be tired efforts by the UNSC to placate Pakistan and China, while not really proposing a practical solution to India’s stubborn recognition of the issue as internal. In that aspect, the UN has failed to properly address the Kashmir issue or urge the international community to take cognizance of the matter.

The looming danger of a nuclear war has also been fueled by recent statements by Pakistani leaders, such as the taunt to “teach Delhi a lesson” by Prime Minister Imran Khan. As a reaction, Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh made a (rather irresponsible) statement that reads like a threat of nuclear war towards Pakistan.

Image 2: Tweet by Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh

India and Pakistan’s unofficial, small-scale proxy wars in Kashmir have kept their internal security constantly on boil. Besides being excluded from the Indian mainstream, J&K has been seen a serious bug in the growth and development story of the country, which seems to be a great concern for the incumbent majority in the government. Kashmir and Kashmiri leadership have been visibly absent from all these discussions mentioned above. Both India and Pakistan have invested and drained a lot of their resources into defence expenditure for the region, and have been building nuclear arsenal as deterrents for one another. While sparring using words and Tweets may not seem like real threats, at a time like this, where terms like ‘nuclear war’ are being normalized and teased by both parties, one would expect for the UN and other powers in the international system to take note and make relevant sanctions to the countries in question.

Keeping this in mind, the UNSC’s maintenance of a respectful distance from the issue has made the situation direr. Its silence has made it clear that Pakistan’s constant cry for help will keep falling on deaf ears, and that India can continue to perceive this as a win on its part, legitimizing its unilateral control on the region more and more. This is bound to rapidly escalate hostility especially from Pakistan, whose leaders have not been shy in reacting emotionally to allegations of deceit and lies by India. While China has publicly sided with Pakistan on the issue and not accepted India’s move, its government has also maintained radio silence with respect to possible moves and discussions for the disputed Aksai Chin region.

That the UNSC took no real collective stance and did not propose any possible sanctions to be placed on either party for non-compliance, has shown its inability to establish its own importance in international decision-making. It further builds the fear among citizens of Kashmir that the issue seems to be too complicated for international bodies to even want to have a stance on it, let alone take strong measures to ensure peace. If anything, this meeting proved that the UN does not really have a place in South Asian politics, and much like the SAARC, it is well on its way to losing importance and respect in the region.

References

Baruah, S. (2019). After 48 years, UN Security Council will talk Kashmir. Retrieved 19 August 2019, from https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/kashmir-india/after-48-years-un-security-council-will-talk-kashmir-4339711.html

Bhattacharjee, K. (2019). What is the UN’s stand on Kashmir?. Retrieved 19 August 2019, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/what-is-the-uns-stand-on-kashmir/article29121025.ece

Chakravarty, I. (2019). The UN in Kashmir: A potted history of resolutions that led nowhere. Retrieved 19 August 2019, from https://scroll.in/article/817144/the-un-in-kashmir-a-potted-history-of-resolutions-that-led-nowhere

Ganguly, S., & Bajpai, K. (1994). India and the Crisis in Kashmir. Asian Survey, 34(5), 401-416.

Khan, A. (2017). Changed Security Situation In Jammu And Kashmir. IDSA Monograph Series, 61.

Noorani, A. (2002). The Dixon Plan. Retrieved 19 August 2019, from https://frontline.thehindu.com/static/html/fl1921/stories/20021025002508200.htm

Raghavan, S. (2010). War and peace in modern India. Ranikhet: Permanent Black.

Ratcliffe, R. (2019). Kashmir: Imran Khan says Pakistan will 'teach India a lesson'. Retrieved 19 August 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/14/kashmir-more-protests-expected-as-india-marks-independence

Shankar, M. (2016). Nehru’s legacy in Kashmir: Why a plebiscite never happened. India Review, 15(1), 1-21. doi: 10.1080/14736489.2016.1129926

UNITED NATIONS INDIA-PAKISTAN OBSERVATION MISSION (UNIPOM) - Background. (2019). Retrieved 19 August 2019, from https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unipombackgr.html