At the 2021 United Nations (UN) Climate Conference in Glasgow, over 100 parties—including governments, businesses, investors, and non-governmental organisations—signed the ‘Glasgow Declaration on Zero-Emission Cars and Vans’ to end the sale of fossil fuel-based vehicles globally by 2040 and usher in a “zero emissions” future. The declaration aims to achieve this mainly by promoting the widespread use of electric vehicles, especially at a time when the idea of green transport has gained popularity and there is increased competition among automakers to manufacture cost- and user-friendly electric vehicles (EVs). Countries are joining the EV bandwagon in droves and global powers like the United States, United Kingdom, the European Union, China, and India have promoted policies aimed at transitioning their economies toward an electric and environmentally sustainable future.

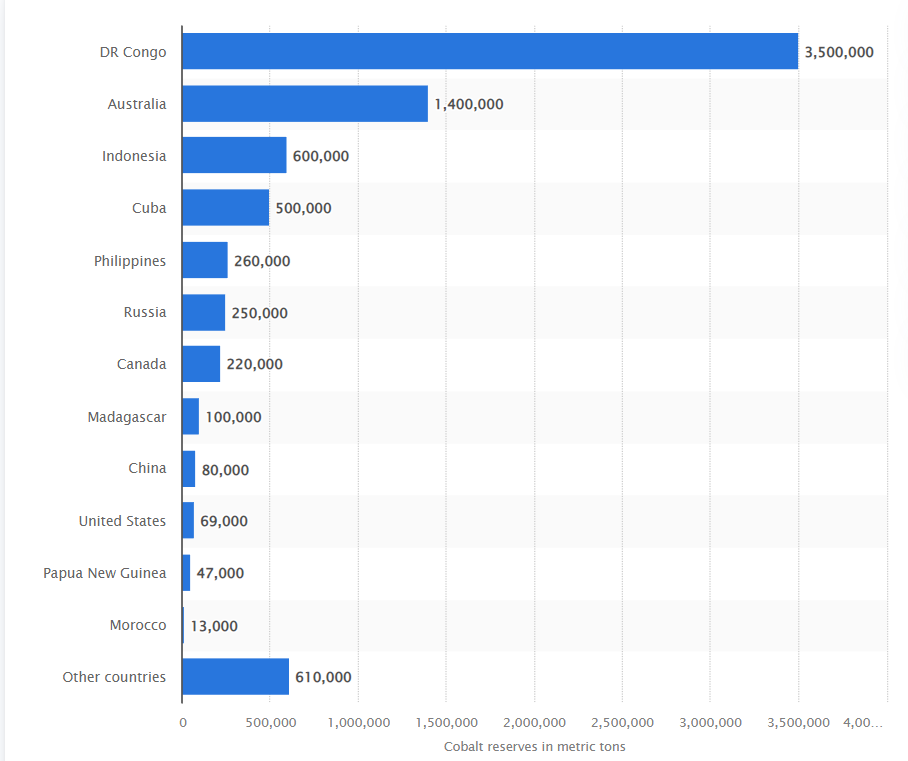

Apart from its apparent benefit to the environment, this global shift towards EVs is said to hold abundant rewards for African countries, since a vast majority of the minerals required for manufacturing EV batteries are found in the continent. For example, it is estimated that the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) alone holds over 50% of the world’s cobalt reserves. Likewise, Zimbabwe and South Africa are respectively among the leading producers of lithium and manganese.

In this context, countries have already invested billions of dollars in mining operations in Africa, creating thousands of jobs, and building infrastructure like railways and power stations. For instance, the Chinese government has outlined elaborate plans to invest in mines in Africa and ensure that a lot of the profits made trickle down to Africans.

With countries setting ambitious goals and companies shifting a major part of their focus to EVs, the demand for battery minerals has skyrocketed, which means an increase in prices. This could mean higher profits for mines, improved wages and working conditions, and more money for governments to undertake human and economic development projects.

However, the reality is much bleaker than what is being painted. In fact, the EV revolution is in many ways a repeat of countries exploiting African resources to the detriment of those countries. International Relations scholar Cobus van Staden argues that an unhealthy competition for minerals could “set off another scramble for African resources with few benefits for most Africans.” He notes that countries have been reckless in their pursuit to capture the EV market and have left a long trail of problems for African countries to pick, including widespread corruption, human rights abuses, and environmental degradation.

China, for instance, which is the world’s largest EV producer and accounts for over 50% of global EV sales, has been accused of fuelling many of these problems. According to reports, Chinese companies linked to Beijing have paid bribes to Congolese politicians to get a monopoly status in the mining industry, which has only further exacerbated Kinshasa’s corruption problem. Many companies are also engaged in illegal and unsustainable mining practices, and Chinese-controlled mines in the DRC are notorious for using child labour. For instance, around 90% of China’s cobalt comes from the DRC and 20% of cobalt from the DRC comes from ‘artisanal mines,’ where child labour is rampant.

The Congolese government has also suspended several Chinese companies for stealing from mines and understating the discovery of minerals. Politicians in the DRC have also admitted that Chinese mining activities were exploiting the country’s wealth and Beijing’s investment has led to nothing but “injustice” for the people. Chinese companies have also been accused of illegal logging and deforestation in pristine lands. Moreover, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has said the “exploitation” of battery raw materials has led to “several environmental challenges,” including the leakage of toxic metals into rivers, streams, and groundwater, and the degradation of ecosystems.

According to Amnesty International, while several companies have adopted cleaner mineral sourcing practices, many businesses still depend on minerals rrom mines where human rights abuses, child labour, and hazardous working conditions are rampant. “As demand for electric cars grows, it is more important than ever that the companies who make them clean up their act,” Amnesty said. “Governments also have a role to play here, and should take meaningful action on ethical supply chains, a priority when implementing green policies.”

However, change will not come easily. Van Staden notes that for countries and companies to adhere to clearer EV mineral sourcing practices, there needs to be “overwhelmingly massive changes in global supply chains and economic relations,” which is highly unlikely to take place any time soon. The sad reality is that whenever a commodity of value, be it diamonds or oil, has been discovered in Africa, it has almost always led to conflict and exploitation. Sierra Leone was plunged into a bloody 11-year-long civil war from 1991 to 2002 over the control of diamonds, foreign oil companies have perpetuated civil wars in Angola and Sudan over trying to control oil reserves, and efforts to control so-called “conflict minerals” like gold and tin have put the DRC in a perpetual state of conflict. The latest rush for African minerals to fuel the EV revolution is no different and, as Van Staden argues, is a replication of “one of the most destructive dynamics in global economic history.”