The concept of balance of power in the international system is usually determined by the world’s sense of which states are rising and falling, often according to modern Western standards. However, this balance is frequently merely psychological and far removed from the physical realities of global power.

In a Darwinian manner, the coronavirus pandemic shows that in times of crisis, a state's efficiency is determined by its reactiveness, rather than its ideology. 'Developed' Western countries have implemented delayed, reactive responses to the crisis and have struggled to adequately contain the spread of the virus in spite of their much-lauded governance styles. In contrast, many oft-criticized governments of the Global South have swiftly enforced control measures in line with the urgency of the situation, albeit with a few systematic flaws. While this has sparked a global conversation about the need to re-evaluate existing Western-influenced concepts of state success and stability, the racialization of the pandemic has been undeterred.

Ever since the outbreak of the virus began in China’s Wuhan district, there have been several disturbing reports of racial discrimination and violence against Asians from across the globe. It may sound harsh, but this is nothing new–the vilification of certain kinds of people is a common symptom of viral outbreaks. European immigrants were stigmatized in the US during the 1853 yellow fever epidemic, East Asians during the SARS outbreak, and Africans have long borne the brunt of prejudice for their seemingly backward health systems that were majorly hit by Ebola. Perhaps this is why the World Health Organization was careful in naming the new coronavirus in a manner that does not even nominally refer to a specific country or region.

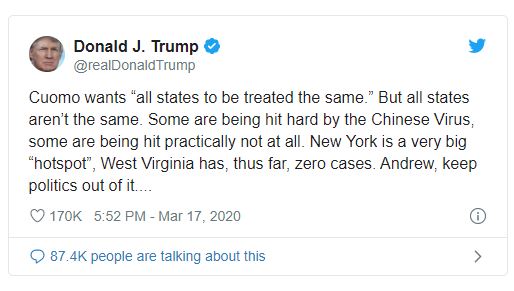

Still, many media outlets and leaders, especially in the United States, continue to refer to the deadly disease as the Chinese or Wuhan virus, even after the WHO officially designated Europe as the epicentre of the pandemic. For US President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the use of these terms is calculated, as they continue to blame the Chinese state for its complicity in spreading the virus and shield similar accusations from Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Such responses make it seem as though it is unfathomable for those in the ‘developed’ world to be equally, if not more, susceptible to a virus compared to those from ‘poorer’ (read: darker) countries. The occurrences of the past few weeks have strongly challenged the international status quo built by over a century of world politics that have relied on and aided the idea of hegemonic global stability.

The fact that Western powers have been so badly hit by the virus and continue to make questionable policy decisions to contain its spread, compared to China, Taiwan, and South Korea, who have acted almost immediately, indicates a shift in world power, and one that is amplified and glaringly visible in the digital age. Gone are the days of the Pax-Britannica, Pax-Americana, and bipolar international systems, where a select few global actors maintained unquestionable superiority over the world’s political, economic, and military capabilities.

It is becoming more evident that the US, once the guarantor of international stability, has systematically and quietly abandoned its global position as a world leader and superpower. Trump has expedited this by weakening the world’s economic governance system and wearing out the country’s capacity to manage international crises. The trade wars, initially against China and then expanded to other states, have eroded the very foundations of the liberal international system of free trade and fair competition that the US was once at the forefront of propagating. In fact, it is difficult to ignore the US’ blatant complicity in countries’ inability to act on the outbreak–crippling aid sanctions on Iran have left the once-powerful Gulf nation in an extreme lurch, with numerous members of parliament and higher officials falling victim to the virus along with thousands of others.

On the other hand, while China dangerously concealed information about the COVID-19 when it first hit, it soon went into a rather aggressive and effective containment mode, placing millions under house arrest and completely sealing its borders. Ironically, the worst-affected country due to Beijing’s decision to limit exports is the US itself–around 80% of its pharmaceuticals are produced in China, along with other essential raw materials used to address non-material national security threats.

The European response has been especially delayed and messy, characterized by an initial denial and encouragement to continue normal life. Countries like France and Germany, where cases are high, have waited until this week to impose strict shutdowns. The EU only managed to reach a consensus on restricting free access in the Schengen area on Tuesday, weeks after the virus had already crossed borders. Italy has imposed the most stringent restrictions than any other country outside of China, but its provisions are ambiguous. For example, it prohibits people from crossing red-zone borders except those with "proven professional needs, exceptional cases, and health issues". But what constitutes these is unclear, and the situation is worsened by the country's mismanagement of its communication strategy. The UK is yet to close schools and put a cap on public gatherings due to its alarming herd immunity approach, but this is not surprising given Boris Johnson’s incompetent leadership.

But as the coronavirus spreads, it is quickly intertwining xenophobia with politics and colouring the responses of government officials. For example, right-wing European parties have distastefully used this crisis to reinstate their calls for tougher immigration restrictions. Italian leader Matteo Salvini was one of the first to exploit the situation to spread his own pandemic of populism, wrongly linking the outbreak to African asylum seekers. Closer to home, the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led SAARC video conference was also marred by political motives, with Pakistani leader Imran Khan bringing up the Kashmir issue at the meeting.

At the same time, countries in Asia and Africa are reacting by closing their borders to those with stronger passports, who are ironically the main culprits of the spread of the virus as they freely and recklessly travel around the world. While Trump pointed to the epidemic as an added reason to build his coveted Mexico border wall, Mexico City announced that it was considering restricting border access to avoid North-South transmission of the virus. In places like India and South Korea, a growing hostility towards European travellers is slowly reversing racist attitudes against those otherwise looked at as role models.

Therefore, while the major war being fought right now is against the virus, the other is for the retention of the Eurocentric social-democratic governance model. The paradigmatic assumption is that democracies would excel in crisis control due to the free flow of information and collaborative spirit between political allies and civil society. Yet, in the case of the coronavirus, many of these countries have failed to take advantage of this. While the US and the UK did not act at all despite having over a month to prepare for the arrival of the virus, Taiwan immediately began monitoring its population. In this pandemic, the major success factors have been an early acknowledgement of the disease’s threat, transparency in knowledge and data sharing, and coordinated governmental efforts for social messaging. This has also paved way for pro-authoritarian leaders and scholars to quickly point out the merits of the Chinese system, its ability to clamp down on its population, and the consequently seamless arrangement of emergency hospitals, medical materials, and testing systems to aid its overburdened healthcare sector.

The politicization of the COVID-19 and finger-pointing by leaders like Trump may just be the downfall of Western society and globalization, unless urgent and competent action is taken. The world is already facing an immense economic fallout due to the virus, which is projected to get far worse over the next few months and will take years to recover from. There is, therefore, a dire need for coordinated transnational efforts to combat the spread of the disease, especially for the US and certain European countries that are heavily dependent on Asia for basic materials and products that are essential to their survival.

Today's multipolar world provides the basis for different actors to indulge in harsher confrontational strategies to defend their national security interests. Yet, despite the fact that the virus is no longer affecting China as badly as it is the Western world, East Asian prejudice and anti-Chinese rhetoric still dominate conservative thought, and is gaining traction and support in the public sphere.

Unless such discrimination and prejudice is not dealt with by state leaders, it will be nearly impossible to enter rational discussions with the actors successfully mitigating this disease for possible cooperation in the virus’ containment. It is crucial that the US and the EU recognize the drastic global economic ramifications of their inactions, that prove to be an existential threat for several states in the Global South that are dependent on them for the sustenance of the global economy.

The WHO has differentiated between countries that have been unable to contain the virus due to the lack of political will rather than a shortage of funds and resources, with Western countries and their important political leaders and celebrities coming out as the victims of their own misgivings. For most other countries at any other point in history, the West is the first port of call when dealing with a deadly disease. This time, the tables have turned drastically and require these leaders to shun their superiority complexes and follow the rest of the world before it is too late.

Reference List

Haynes, S. (2020). As Coronavirus Spreads, So Does Xenophobia and Anti-Asian Racism. Time. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://time.com/5797836/coronavirus-racism-stereotypes-attacks/.

Kayyem, J. (2020). Trump Leaves States to Fend for Themselves. The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/america-has-never-had-50-state-disaster-before/608155/.

Kempe, F. (2020). Op-Ed: The coronavirus outbreak is already changing the world. CNBC. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/07/op-ed-the-coronavirus-outbreak-is-already-changing-the-world.html.

Konneh, A. (2020). What the West Can Learn From Africa’s Ebola Response. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/16/coronavirus-ebola-liberia-sirleaf-west-can-learn-from-africa-response/.

McLaughlin, T., & Serhan, Y. (2020). The Other Problematic Outbreak. The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-covid19-xenophobia-racism/607816/.

Meisenheimer, M (2020). Democracy? Autocracy? Coronavirus Doesn’t Care. Thediplomat.com. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/democracy-autocracy-coronavirus-doesnt-care/.

Unay, S. (2020). ANALYSIS - Coronavirus, petrol wars and global crisis. Aa.com.tr. Retrieved 18 March 2020, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/analysis-coronavirus-petrol-wars-and-global-crisis/1764635.

Image Source: Schengenvisainfo.com