Malaysian lawmakers have introduced an anti-party hopping bill in order to combat a chronic malaise in local politics that has seen three prime ministers in a single parliamentary term and 39 parliamentarians switching political allegiances since the 2018 general election. Yet, while the law is intended to bring a semblance of stability to the volatile cauldron of Malaysian politics, many worry that it could create more problems than its solves.

Party hopping in Malaysia is common, as no single party is able to form government without gathering the support of several coalition members. Such coalitions are usually formed on the basis of fragile trust and promises. This is also how the Malaysian political crisis peaked in 2020. The crisis began after then-Prime Minister (PM) Mahathir Mohamad refused to initiate the process of handing over power to his designated successor Anwar Ibrahim, as he had promised ahead of his 2018 general election victory. Mahathir’s decision to renege on a promise caused a division in the ruling Pakatan Harapan coalition, with many lawmakers switching allegiances.

Courts have historically upheld the democratic and constitutionally-enshrined principle of freedom of association. However, frequent defections have forced the government to consider amending Article 10. One of the chief reasons is to protect parliamentary majorities so that prime ministers are not repeatedly forced to dissolve the Cabinet.

At the same time, citizens consider party-hopping to be a betrayal of the voters’ mandate, assuming that voters are primarily motivated to vote for a particular political party rather than the candidate themselves. This is especially true in Malaysia, where citizens tend to back candidates from established parties because independent candidates rarely win.

Deputy President of the newly set up Parti Bangsa Malaysia Larry Sng has stated that the party's top agenda is to enact Anti Hopping Law to prevent MPs from switching political parties after being elected. "We need to stop this. It's a betrayal to our voters." says the MPOB Chair pic.twitter.com/ER8c8AciPm

— The Borneo Ghost (@theborneoghost) November 22, 2021

Reinforcing this point, lawyer Bastian Pius Vendargon told Free Malaysia Today that citizens’ confidence in the current process is very low, as they believe that party-hopping is not done due to differences of opinion but for personal gain. Keeping this in mind, he has put his weight behind the proposed law, saying, “It is to ensure that the will of the voters is not thwarted by unscrupulous elected representatives. If the bill is not passed and does not become law, immoral representatives of political parties can continue to exploit their positions for personal gain, monetary or otherwise, at the expense of their voters. It also leads to political instability.” Vendargon thus argues that the law would uphold constitutional and electoral rights.

These claims have been echoed by electoral reform group Bersih, which has said that the passage of an anti-defection law in Parliament would help restore public confidence in the electoral system.

However, the cost of this “stability” would be that lawmakers are no longer fully empowered to express dissent against their party, wherein those with differing viewpoints are forced to align their views with those of their party or the ruling coalition. Moreover, the ruling party could misuse the law to remove parliamentarians who do not toe the line, which threatens to erode freedom of speech and expression.

Referring to the broad scope of the law, opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, whose Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition has pledged support to the ruling government until , has raised concern that the wording of the amendment is too vague. He has instead called for the restriction to be limited to political defections. To this end, the PH sent the government its own version of the draft. The opposition added that although it expects the government to counter its draft, PH would consider the new law “as long as defections are clearly defined.”

It is because of people like Anwar Ibrahim that Malaysia needs an anti-hopping law. It was Anwar who started this practice in 2008 with his "16 September" plot. Today, because of Anwar, party-hopping has become budaya politik Malaysia. pic.twitter.com/D0ASl32f1S

— Raja Petra Bin Raja Kamarudin (@RajaPetra) August 29, 2021

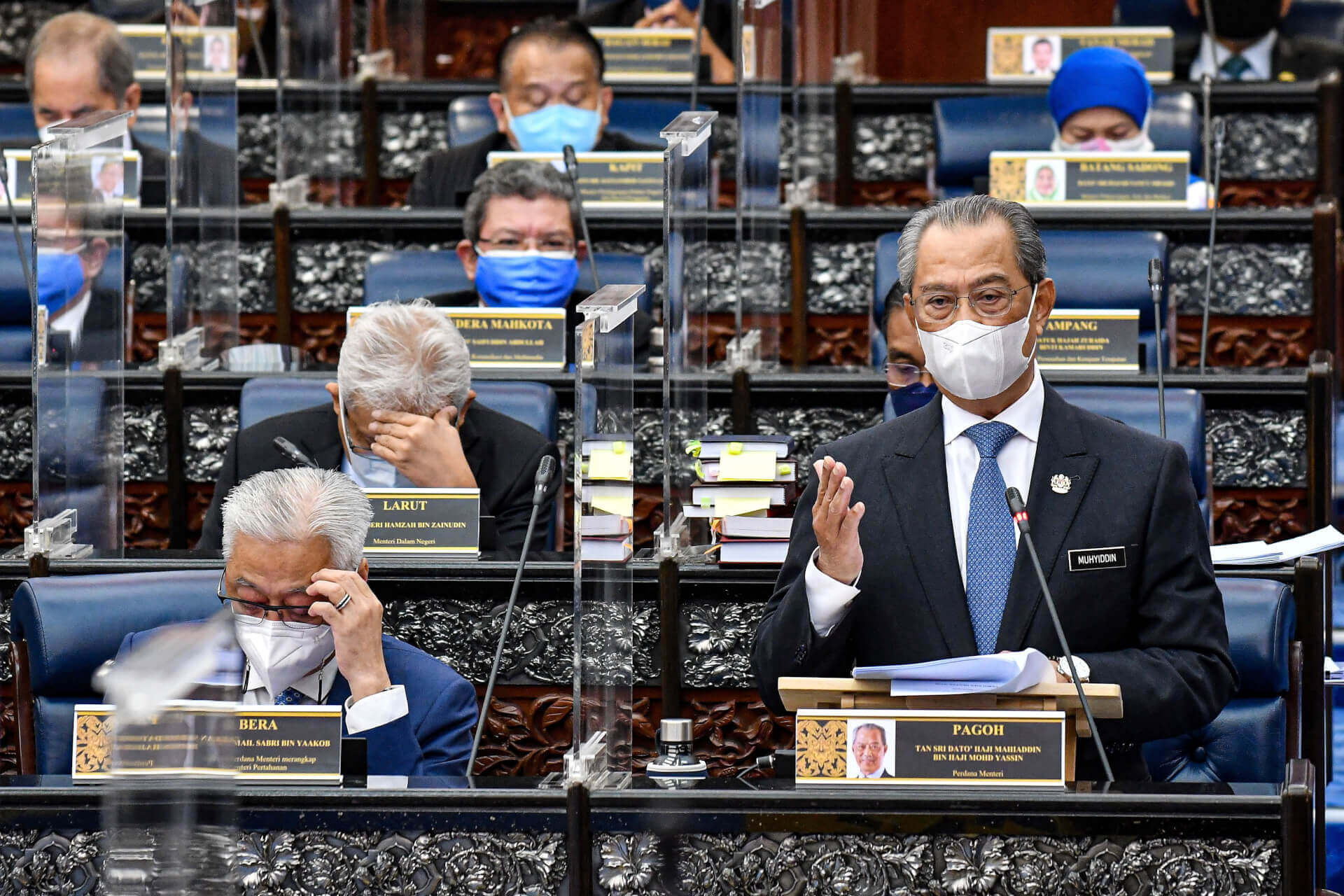

In fact, former Prime Minister (PM) Muhyiddin Yassin, who is part of PM Ismail Sabri Yaakob’s government and was overthrown due to internal dissent, voiced similar concerns. “We do not want this to be used to restrict freedom of association of MPs in realms outside of their political party membership,” he has said.

As things stand, politicians are able to switch allegiances without losing their seats. However, if the law is passed, elected representatives who resign from their seats or are sacked by their party would be barred from contesting for five years. Subsequently, their seat would be declared vacant and they would be required to re-contest their seat in a recall election after a five-year hiatus

Aside from the fact that elections are an expensive affair, such a long wait period would likely prevent lawmakers from resigning from their party just to contest for the same seat and get a fresh mandate. Therefore, there is a strong chance that politicians with differing views could choose to stay in the same party and give the appearance of allegiance. Such a consolidation of power would be artificial and could create even bigger tensions within a party, as differences would be allowed to fester, stew, and grow. This could result in massive upheaval at the end of terms, when lawmakers would be legally permitted to switch parties without fear of reprisal.

The planned amendments to the federal constitution to make way for an anti-party hopping law must not be allowed, as it could grant broad powers to the government to remove elected representatives on a whim, young voters association Undi18 said. #malaysia #Politics pic.twitter.com/wXyvkr3N2w

— Minika Rahim (@MinikaRahim) April 9, 2022

Moreover, while the law is likely to artificially prevent individual legislators from abandoning their party, it does nothing to address the constant upheaval caused by entire parties withdrawing their support for the ruling coalition, which leads to frequent changes in power and elections and has been the main source of political instability in Malaysia in recent years. For example, last July, the United Malay National Organisation (UMNO), Malaysia’s biggest political party and a key ally in the ruling coalition, withdrew its support for then-PM Muhyiddin Yassin and called on him to resign for failing to manage the country’s COVID-19 crisis. The move was the first of several incidents that shook the administration and eventually forced Yassin to step down.

Ironically, the passage of this Bill is dependent on the uniformity of decisions taken by parliamentarians and will affect the stability of the current government itself. The opposition, which has a confidence and supply agreement with the ruling government to ensure temporary stability, has warned that it will withdraw its support if the government fails to introduce the anti-party hopping legislation, a key condition of their pact. To truly introduce a degree of stability, the government must seek to combat defection both at an individual and a party level. At its core, the bill needs to provide a clearer definition of what constitutes defection because, as things stand, the proposed law is merely designed to stomp down on freedom of expression and differing viewpoints, which should be pillars in any healthy, functioning, and pluralistic democracy.