On 24 July, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Bill, 2019 which was introduced by Home Minister Amit Shah in the Lok Sabha, was passed despite a great deal of concern from the Opposition. In a previous article, we discussed the new provisions of the National Investigation Agency (NIA) Amendment Bill, 2019, which has strengthened the power roles held by the Agency. The UAPA Bill, too, includes clauses that increase the authority of the NIA. In this article, however, I will be focusing specifically on the clause that allows for the designation of the term ‘terrorist’ to individuals, and what the ramifications of such an amendment would be.

It is important to note that mens rea in criminal jurisprudence, which refers to criminal intent, begins with the individual, while organizations are only a matter of contention once a conspiracy is established. Therefore, in most counter-terrorism practice, it is assumed that the intention to commit a terrorist act is usually the outcome of a criminal mindset in an individual, and later a group of individuals. Prior to the amendment, the UAPA only recognized ‘terrorist’ and ‘terrorism’ to be associated with the actions of a recognized terrorist outfit. In Shah’s speech in Parliament, he highlighted the phenomenon where leaders of recognized terrorist outfits continue influencing others simply by changing the name of the organization. Hence, there is a dire need for the law to target the individual leader first, and then the organization to which they belong. This is part of the reason why, post-26/11, Hafeez Saeed, the alleged mastermind behind the attack, was denied extradition and later on granted bail on the grounds that the Lashkar-e-Taiba’s political wing, the Jamat ud-Dawah of which Saeed was a top leader, was not a banned organization in Pakistan.

More importantly, this amendment broadens the scope of the UAPA to encompass what is known as ‘lone wolf’ or ‘lone actor’ terrorism. Lone actor terrorists are those offenders and offender dyads who might have been motivated to act on a group’s goals, but whose acts were directed and conceived by the individual, without external direction or command. In the USA, according to the FBI, this may include dyads such as the 2013 Boston Marathon bombers or the 2015 San Bernadino shooters.

Historically, India has been comparatively immune to lone wolf terrorism, but of late there have been a few incidents of Indian youth becoming radicalized. Two examples come to mind in this regard, the first being Kalyan’s Areeb Majeed, a young man who travelled with three friends to Syria to fight for the ISIS. Majeed was arrested in 2014 after his deportation to India from Turkey. The second would be the case of Bengaluru’s Mehdi Masroor Biswas, who was arrested in 2014 for running an ISIS propaganda-based Twitter account with over 17,000 followers. The charges against Biswas were on the basis of “distributing... messages [and] organizing hashtag campaigns for ISIS, encouraging tweets on popular ISIS-related hashtags, and utilizing software applications that enable ISIS propaganda”.

In his passionate defence of the Bill, Shah said, "There's a need for a provision to declare an individual as a terrorist. The United Nations has a procedure for it, the United States has it, Pakistan has it, China has it, Israel has it, European Union has it; everyone has done it". In a 2009 interview, Noam Chomsky referred to a case where the USA’s Office of Foreign Assets Control identified an Islamic charity named Al-Barakat and accused them of transferring funds to the Al Qaeda. This caused the charity to shut down, and the US Government publicized this move as a great victory in the “War on Terror”. Later, they found out that Al-Barakat contributed largely to the sustenance and economy of Somalia as it was financing banks, private enterprises, and business activities in the poverty-stricken country. The US quietly conceded that their accusation was a mistake, but by then the blow to the Somalian economy was already quite severe.

Hence, while Shah’s argument is reasonable, there is a significant gap between counter-terrorism theory and practice, not just in India but in these other countries that he holds to such high regard. The theoretical study of terrorism is intrinsically fragmented as it is, and involves a deep understanding of diverse disciplines such as criminology, psychology, anthropology, sociology, history, economy, political science, engineering, and computer science. Even though there has been an inquiry into how these fields can be used in identifying, prosecuting, and rehabilitating a terrorist from an organization, the application of this new subset within terrorism research to the study of lone actor terrorism has not yet reached its fullest potential.

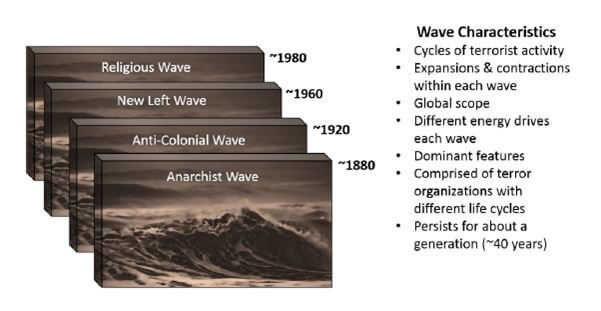

David Rapoport’s wave theory of terrorism states that each wave can be defined on the basis of its ideological motivations, preferred weapons, targeted victim groups, and line of attack. They are summarized in the graphic below:

Fig. 1 Rapoport's wave theory of modern terrorism

For example, the signature anarchist attack employed an ideology that was motivated by the perceived notion of democratic failure, radicalism, and nationalism, and used bombs and firearms to assassinate opposing industrial and political figures. On the contrary, the fourth ‘religious’ wave is reflective of anti-democratic and anti-secular extremists, mainly Islamic fundamentalists, who use technologically advanced information and communications and unconventional weapons to target soft, Western targets in public at large. While Rapoport’s waves have contributed massively to terrorism theory, its linear nature makes it difficult to contextualize and understand the simultaneous existence of these waves in certain societies, for instance, Pakistan, which has a convoluted mix of homegrown, state-sponsored, and cross-border terrorism motivated by varying factors. A few authors have identified the lone wolf terrorism phenomenon as a newer, fifth wave of terrorism in the post-9/11 era that favours communications. Gallagher, who is of the opinion that the religious wave put forth by Rapoport contains sub-waves of dilapidating religiosity, believes that lone actor terrorists are one such sub-wave. He suggests that the fifth wave — more a tsunami — is the “terror of the individual”, characterized by a cycle of extremist activity committed by people with social agendas that go far beyond jihadism alone.

Social identity theory, which is often applied to theories of counter-terrorism, holds the notion the individual first possesses a strong sense of identity within a certain ‘ingroup’, after which they develop hostility towards a clearly defined ‘outgroup’. Other social identity theorists are of the belief that individuals who self-identify as being part of a central group that has not formally accepted them as full members yet, are more likely to participate in extreme acts ‘on behalf’ of said group. The Freudian psychoanalytic theory can also provide an explanation as to how radical ideology manifests in a lone actor’s self-destructive and irrational behaviour. The mimetic theory also elucidates how individuals tend to mimic real or imagined third parties; role models whom we imitate in the hope of resembling.

Therefore the combination of wave, social identity, psychoanalytic, and mimetic theories, doubled with the current technological revolution, can explain to some extent the growing crop of lone wolf actors and the legitimacy they seek and provide by the use of digital means. It is imperative, then, to evaluate the use of social media and the internet by lone actor terrorists in academic literature surrounding this discourse, as the digital space is where this phenomenon seems to be brewing. In the security field, there is a saying that “threat = intent + capability”. Someone’s desire to perform a destructive act does not necessarily mean that they have the means to do so. Very often, it is difficult to ascertain whether a statement is being made by a potential lone actor or a citizen venting out a latent thought that they do not intend on acting upon. Therefore, engaging in online surveillance of individuals tends to be problematic when the person is lawfully exercising their rights to free speech and expression, however distasteful those views may be.

In India, the first line of defence with respect to radical elements in the cyberspace is usually technical intelligence capabilities, including monitoring websites, social media, chat logs, and emails. However, since most of the control of these internet mechanisms lie with Western companies, India has to seek coordination with these intelligence agencies. Our own intelligence agencies lack skilled manpower that is sufficient to gather intelligence on specific individual elements in our extremely populous society. Human intelligence and on-ground surveillance remain inadequate methods to pre-empt and prevent lone wolf attacks. In the past few years, many Indian citizens have been arrested on suspicion of sedition and antinational activity based on Facebook posts and WhatsApp forwards that mainly reflect dissenting ideas, and this move has been criticized by the Opposition as well as activist groups in the country for infringing upon the individual’s right to expression.

Keeping these intricacies in mind, there needs to be a legally-defined mechanism by which lone wolf actors can be properly identified, which India currently lacks. Public fixation on ideology is a major distraction from finding practical solutions to stopping such attacks, and in the West, the profiling of lone wolf acts as terrorist activities vs. workplace violence, or hate crimes carried out by mentally disturbed individuals is a matter of contention as this profiling is usually done on the basis of ethnicity, nationality, and religion.

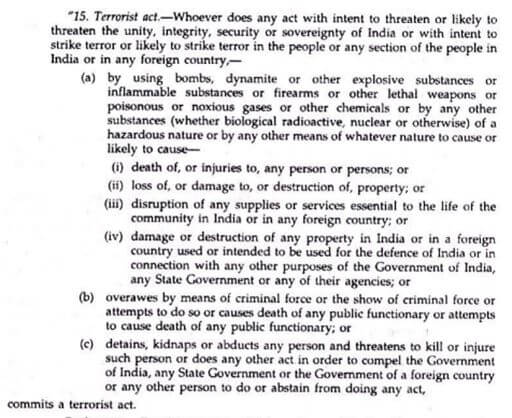

India faces such challenges as well, albeit with different societal intersections. Currently, the UAPA defines a ‘terrorist act’ as follows:

Fig. 2 Definition of 'terrorist act' sourced from the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967

This definition does not specify any ideological, ethnic, or religious markers for an organization or individual with respect to profiling, yet in practice, these categories seem to play an important role. The Act specifies two ways to proscribe a group as a ‘terrorist organization’. The first is to declare the organization as an “unlawful association”, and have that declaration adjudicated upon by an independent authority or Tribunal (as mentioned in the original text of the UAPA 1967). The second method is that of executive fiat, where the Central Government has the power to designate an organization as a ‘terrorist organization’ in the First Schedule of the UAPA. In a way, this provision, which was granted to the Central Government when the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) was merged into the UAPA in 2004, in a way nullifies the relatively more stringent process laid out in the previously mentioned method.

The very apparent biases of Indian governments through the years have led to this line being blurred, more specifically with regards to dissenting activity in the country, where the Act has been criticized for violating individuals’ freedom of association especially in the case of Kashmiri separatist and Naxalite activity. In the more recent case of Romila Thapar vs. Union of India (2018), which is based on the arrests of five journalists after the Bhima Koregaon incident, the UAPA has also been a convenient tool to detain people based on their membership of a banned association, in this case, the Communist Party of India (Maoist). This history of where this Act has been applied in executive action as well as jurisprudence makes it even more difficult to expect due process in identifying lone actors, especially since the parameters to proscribe someone as a terrorist have not been set in stone. Shah’s reference to the internet troll-created term “urban Maoist” in Parliament, along with ambiguous references to texts that are being distributed to incite a so-called antinational sentiment, begs the question — who is the real target of this amendment?

By the very definition of terrorism in the UAPA, it can be argued that certain acts of mob lynching and cow vigilantism can constitute lone wolf terrorism, where the some of the cases fall well within the ambit of the current definition of ‘terrorist act’. In many of these cases, the perpetrators have threatened the “unity, integrity, security” of India, and the people or section of people have by “means of criminal force” threatened to kill or injure persons in order to “compel…any other person to do or abstain from doing any act”. The perpetrators also meet the criteria of the psychoanalytic, social, and mimetic theories mentioned above: even though the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is not recognized as a terrorist organization, the adoption and imitation of its more extreme ideologies by individual citizens towards selected minority groups — most recently even against a minority member of the Armed Forces — should be treated with the same severity as other terrorist acts. Yet, the incumbent government is unlikely to deem these as such on the basis of ideology. Instead, quite ironically, Shah is set to lead a special group to combat these incidents of lynching.

The legal recognition of lone wolf terrorism is, indeed, a laudable move by the BJP-led government. But much like the USA, which struggles with categorizing lone actor acts due to its ethnically and ideologically diverse society, India needs to recognize its setbacks and leave behind its biases before leaving such an unsettling amount of power in the hands of the Centre as approved by the 2019 UAPA and the NIA Bills. Unless a transparent set of processes and parameters to proscribe terrorist status to organizations and individuals is not defined, the Act may not be sufficient to successfully curtail radical elements without infringing upon individual rights to association and expression.

References

Ade, P. (2015). Lone wolf Terrorism: How Prepared Are India’s Intelligence Agencies? Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses,7(6), 4-11. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26351360

Gallagher, M. (2017). The 2016 ‘Lone Wolf’ Tsunami - Is Rapoport’s ‘Religious Wave’ Ending?. Journal Of Strategic Security, 10(2), 60-76. doi: 10.5038/1944-0472.10.2.1584

Hazen, L. (2019). A Phenomenological Inquiry into the Efficacy of Profiling Lone-Actor Terrorists (Ph.D). Northcentral University.

Khabeer, S., Sheikh, F., & Faruqi, D. (2019). Treating Lone-Actor Terrorists Like School Shooters - The Islamic Monthly. Retrieved 30 July 2019, from https://www.theislamicmonthly.com/treating-lone-actor-terrorists-like-school-shooters/

Mandar, H. (2018). ‘Urban Maoists’: a curious new creature in Modi’s India. Retrieved 31 July 2019, from https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/2162232/urban-maoists-modis-india-if-you-are-right-you-must-be-left

Noam Chomsky interviewed by The Imagineer. (2009). Retrieved 30 July 2019, from https://chomsky.info/20090519/

Singh, A. (2019). Designation of Individual as Terrorist - The Right Step. Retrieved 31 July 2019, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/designation-individual-terrorist-right-step-abha-singh/

Suresh, M. (2019). The slow erosion of fundamental rights: how Romila Thapar v. Union of India highlights what is wrong with the UAPA. Indian Law Review, 1-12. doi: 10.1080/24730580.2019.1640593

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Bill, 2019. (2019). Retrieved 30 July 2019, from https://www.prsindia.org/billtrack/unlawful-activities-prevention-amendment-bill-2019

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. Sourced from https://mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/UAPA-1967_0.pdf

Fig. 1: Rapoport's wave theory of modern terrorism. Symbol ~ = approximately. Adapted from “The Four Waves of Modern Terrorism,” by D. C. Rapoport, 2004, in A. K. Cronin and J. M. Ludes (Eds.), Attacking Terrorism, Elements of a Grand Strategy, (pp. 217-224). Copyright 2004 by Georgetown University Press. “Wave, Tide, Ocean, Water, Splashing, Dynamics,” by unknown photographer, 2009. Reprinted with general permission under CC0 Creative Commons license. Copyright 2018 by Pixabay.

Cover Image: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats