The Indian Supreme Court recently granted bail on medical grounds to 82-year-old renowned poet-activist Varavara Rao in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon/Elgar Parishad case, wherein he was charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for allegedly plotting to overthrow the state. Rao spent nearly two-and-a-half years in prison, with his case not even progressing to the trial stage. While Rao was a beneficiary of the course correction, his co-accused, 84-year-old tribal rights activist Father Stan Swamy, died in custody while his medical bail plea was being heard in the Bombay High Court.

The case once again spurred conversation on the “to bail or not to bail” argument, which has gained renewed momentum in recent weeks. On July 8, Alt News co-founder Mohammed Zubair, who was arrested in connection with a “highly provocative” tweet dating back to 2018 that allegedly attempted to “outrage religious feelings” and “promote enmity between different groups,” walked free after he was granted interim bail by the apex court following a month-long tug of war.

Bail Ought to Be the Rule

Against this backdrop, in an address to the Rajasthan National Assembly last month, Chief Justice of India (CJI) N.V Ramana lamented the surging trend of “indiscriminate arrests,” saying it risks the country descending into a “police state.”

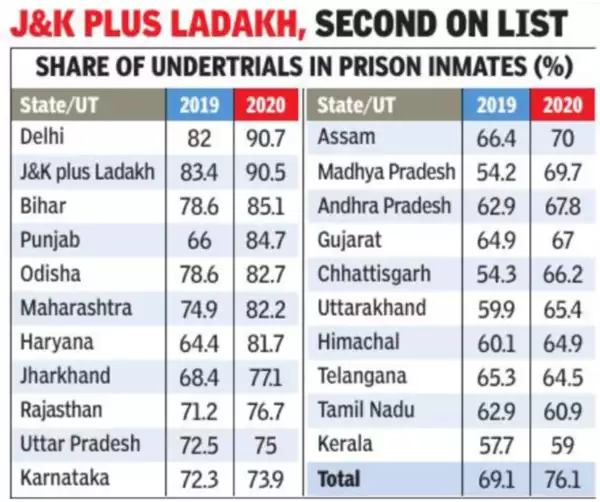

He revealed that more than 80% of the 600,000 prisoners lodged in Indian prisons are undertrials, most of whom are charged with petty offences. Prolonged detentions foment a scenario wherein “the process becomes the punishment.” Incidentally, the “process” in Swamy’s case ended with the ultimate “punishment” of death.

Ramana’s comments build upon a July 11 ruling in the Satender Kumar v/s Central Bureau of Investigation case, in which Supreme Court justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul and M.M Sundresh urged the government to re-examine the need for a new bail act that streamlines and standardises the procedure.

In fact, the top court has repeatedly reiterated the principle “bail is the rule, jail is the exception,” noting that arrest is a “draconian” measure that must be used sparingly, lest we risk endangering all forms of dissent and opposition to those in power.

Archaic Laws

While no Indian statute currently defines bail, the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) of 1976 categorises offences into bailable (Section 436) and non-bailable (Section 437) offences—in the latter case, the fate of the bail applications is subject to the magistrate’s discretion.

The CrPC was first drafted by the British, led by Lord Macaulay, in 1861. Though it was amended multiple times before coming into force post-independence, it retained most of its pre-independence restrictions. These restrictions, however, were framed against the backdrop of the 1857 Indian Rebellion and were designed to crush India’s quest for freedom.

It must, therefore, be asked whether the colonial mindset that framed these laws is still relevant in modern Indian society.

Stringent Conditions for Bail

Awarding overarching discretionary powers to magistrates has plagued the justice system with ambiguity, arbitrariness, and unpredictability. In some cases, the bail conditions imposed on the accused contravene logic; for instance, Zubair’s bail conditions initially mandated that he should not be allowed to post “any tweets”—a significant departure from the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution.

Moreover, in a country that suffers from weak judicial infrastructure, delayed proceedings, rampant corruption, poverty, and illiteracy, a bail petition itself remains out of reach for many. Additionally, certain laws go to the extent of imposing a “statutory bar” on granting bail, or place stringent criteria, specifically in cases involving the Sedition law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, and the like.

Colonial-Era Remnants of the CrPC Have Outlived Their Purpose

India must thus re-assess the letter and spirit of the CrPC as inherited from our colonial masters on at least the following three counts.

To begin with, diametrically opposed to the foundational values of present-day India as enshrined in the Constitution, certain elements of the colonial-era CrPC do not recognise arrest as a fundamental liberty issue in itself. Indiscriminate arrests, therefore, violate fundamental rights under Article 20 (Protection with Respect to Conviction for offences), Article 21 (Right to Life and Liberty), and Article 22 (Protection Against Arrest and Detention).

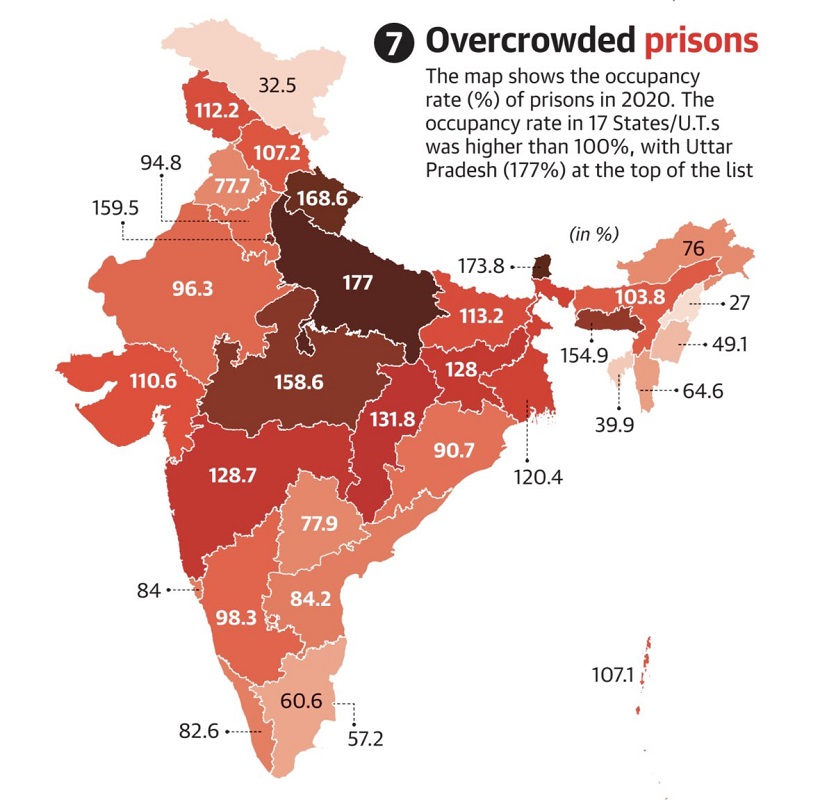

Secondly, the continuation of stringent bail provisions in modern independent India has truncated the delivery of justice, as evidenced by the swelling numbers of inmate populations and prison overcrowding; according to the Prison Statistics of India Report 2020, over 15 states are operating at over 100% capacity. To this end, the Supreme Court has directed state governments to proactively address the issues of both “unwarranted arrests” and “clogging of bail applications.”

Thirdly, the ideals of reformative justice centre around a progressive approach that is enshrined in a democratic, civilised, and ethical society governed by the rule of law. This is in stark opposition to a foreign colonial state whose legislations projected a retributive form of justice.

Lessons for India: UK and US Bail Laws

Keeping this in mind, the world’s largest democracy stands to learn a lot from the world’s oldest democracies in taking a leap forward to decolonise our bail laws. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Bail Act of 1976 aims to reduce the size of the inmate population by recognising a “general right” to bail, whereby the onus of proof lies on the prosecution to conclusively prove that the accused will not surrender, commit an offence, or interfere with witnesses to obstruct justice. Additionally, it offers free legal aid to those in need to ease the application process to grant bail.

This mirrors bail provisions in the United States, where the Constitution declares that “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” To this end, its Bail Reform Act of 1984 provides clear and concrete guidelines on granting bail, with the US Supreme Court declaring over three decades ago that “In our society, liberty is the norm, and detention prior to or without trial is the carefully limited exception.”

Democratise and Decolonise India’s Laws

CJI Ramana’s remarks thus nudge our national conscience to embark upon the process of deconstructing a colonial-era iron-clad “police state” into a more compassionate “people’s state.” In this respect, the judiciary has taken nascent initiatives to re-examine the constitutionality of pre-constitutional era legislations and called for meaningful reform of India’s bail laws.

The executive and the legislative wings of the state must follow suit and reinstate the values of liberty, equality, fraternity, dignity, and justice in our criminal jurisprudence. Codifying a Bail Act that focuses on ensuring the presence of the accused at the different stages of the trial and recognises bail as a right, and not a privilege, can help assuage the twin challenges of unnecessary arrests and a booming undertrial population.