On September 17, the people of Israel voted in a landmark do-over parliamentary election. This is the first time that the country has held two elections in a year, which was triggered after the incumbent Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu failed to form a coalition government in April. The stakes are high, as the winner of this election will have the power to change the future of Israeli democracy itself. How will the outcome of this election affect Israel’s domestic functioning and foreign relations?

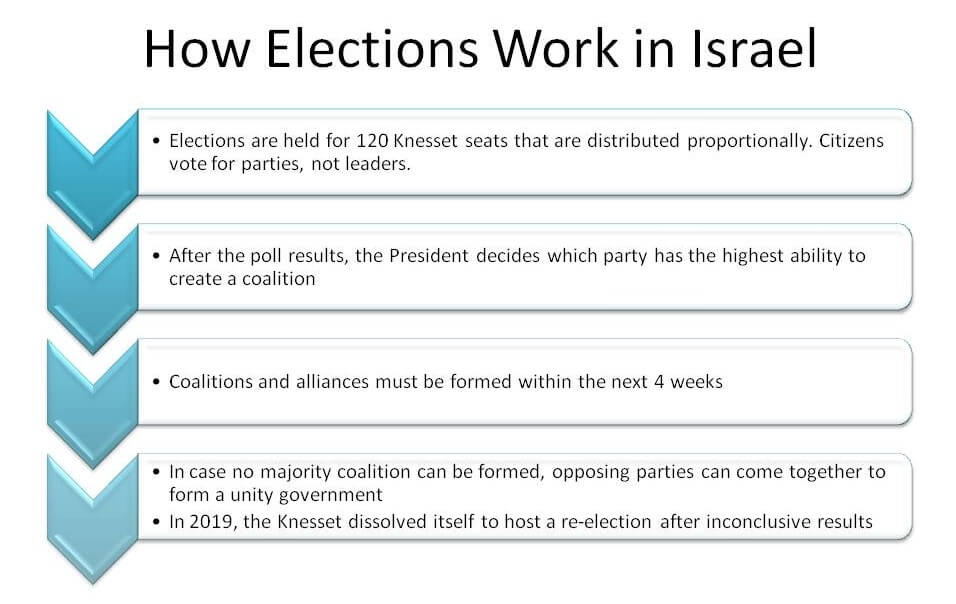

Seats at the Israeli parliament, the Knesset, are awarded by proportion. This means that parties get a certain number of seats depending on the share or percentage of national popular votes they get. In order to qualify for seats at the Knesset, a party has to win at least 3.25 percent of the popular vote, which is usually attainable by a large number of different parties in Israel. There are a total of 120 seats, and parties need to secure at least 61 to form a governing majority; yet, no party has been able to single-handedly attain an outright majority till date. Instead, larger blocs have been forming blocs and coalitions with smaller allies.

After the election results, the President (who is elected by the Knesset every seven years) meets with party heads and selects the party that has the highest ability to form a coalition. Usually, this is the party with the largest faction, which then is given four weeks to create the coalition. This new government is given a four-year term, but due to the nature of the electoral process and the high number of parties, the system is extremely fragmented and disagreements between coalition parties often lead to early elections.

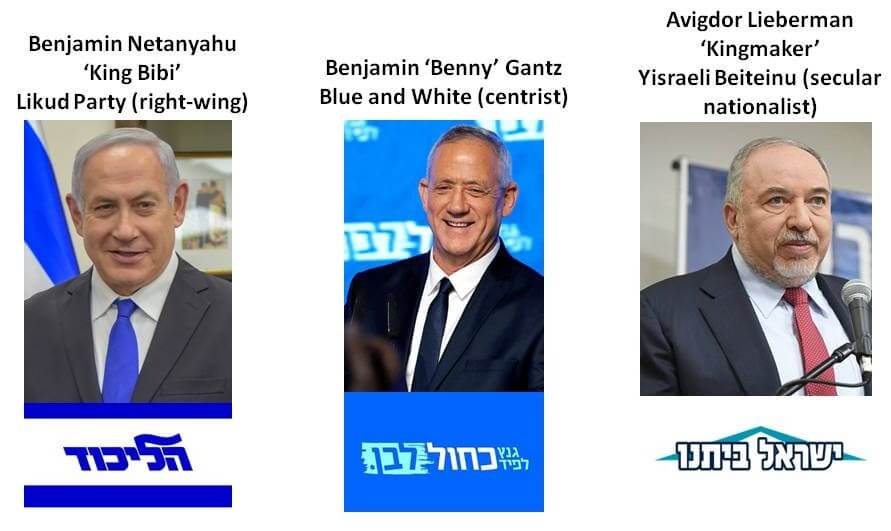

The current election has around 30 parties competing, of which the major players are Netanyahu and his right-wing party Likud, Benny Gantz from the centrist Blue and White party (BW), and Avigdor Liberman’s right-wing secular nationalist party Yisrael Beiteinu (YB).

Likud believes in a strong national security policy which is based on heavy military force, has historically opposed Palestinian statehood, and supports Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Although a secular party, Netanyahu’s leadership in the Likud has forged coalitions with ultra-Orthodox groups in the past.

BW (also known as Kahol Lavan), a political alliance between three liberal parties, describes itself as a “pluralistic party representing all citizens on the political and religious spectrums”. Tenets of the party include amending the Nation-State Law to include minorities, investing and expanding education and healthcare, and re-entering negotiations for a peace agreement with Palestine.

Lastly, YB which started as a secular party for Russian-speaking Israelis, has gained political traction to become the third-largest party as it encourages Jewish immigration, demands compulsory drafting for all including the ultra-Orthodox, and is anti-religious coercion; yet YB maintains a tough stance on security policy based on preemptive action.

Why a re-election?

Israel has seen a series of centre-right coalition governments ever since Netanyahu took office in 2009. After the April 2019 election saw a vote deadlock between Netanyahu’s right-wing party Likud and his centrist opponent Benny Gantz from the Blue and White (BW), the Prime Minister attempted to build a coalition entirely comprised of religious and right-wing parties, which make the majority Knesset seats. However, he was too ambitious in trying to pair Lieberman’s right-wing secular nationalist party Yisrael Beiteinu (YB) with the ultra-Orthodox religious parties, as Lieberman and the YB fundamentally oppose the special privileges that are provided to religious Jews under the current Israeli law; rather, they demanded a bill that undermined the exemption of ultra-Orthodox men from mandatory military service.

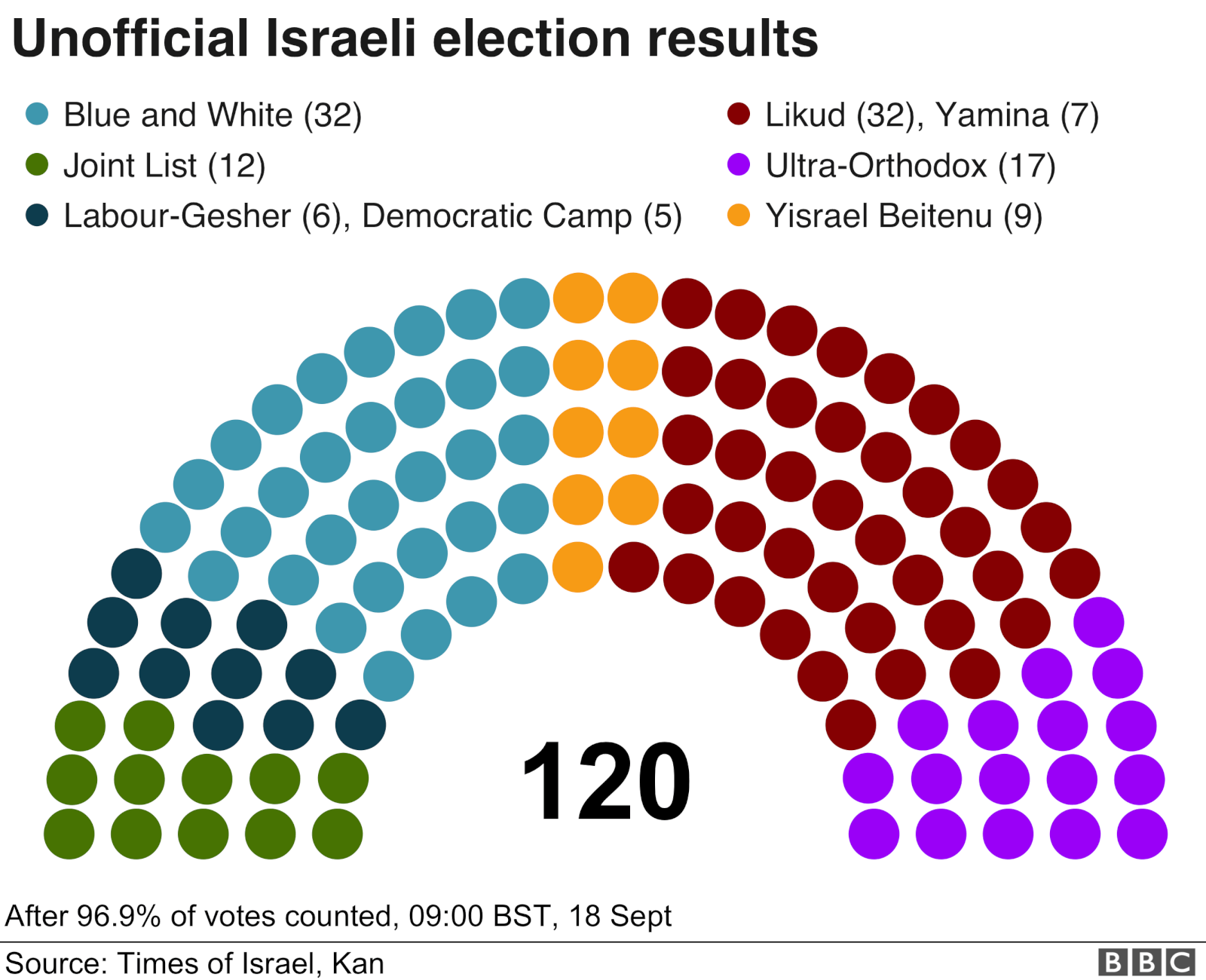

Without the support of ‘kingmaker’ Lieberman, ‘King Bibi’ Netanyahu was not able to garner the votes necessary to create a majority, as he was unwilling to let go of the ultra-Orthodox support. Consequently, he managed to convince the Knesset to dissolve itself and host a re-election, marking the first time that two elections have been held in the same year. Currently, the poll results reflect another deadlock, with the latest count showing Gantz in the lead but still far from a majority. According to most observers, poll experts, and Lieberman himself, the most plausible outcome to this situation is a centre-right national unity government, which will essentially be a power-sharing agreement between Likud and BW. In such a case, it is possible for both Netanyahu and Gantz to share the role of Prime Minister on a rotational basis — this has happened before in. However, Gantz is unwilling to form a coalition unless Likud boots Netanyahu from its top position due to his indictments. Lieberman has kept his allegiances up in the air as he waits for the other two major parties bargain with one another. If there is no consensus this time around, Israel may even see a third election this year.

A major unknown factor in this whole story is the reaction of the public to the possibility of a change in the existing balance of power among the branches of government, including a proposed immunity for Members of the Knesset (MKs) from criminal proceedings. Until an amendment in 2005, MKs were given automatic immunity from prosecution under law, unless decided otherwise by the Knesset. Currently, MKs must request the Knesset to provide them with immunity. Once the Knesset makes a decision in committee and in the full chamber, the Supreme Court may contest this outcome. Netanyahu and his allies have proposed returning the law to the same one that existed before 2005, with an added clause of blocking any intervention by the Supreme Court in the Knesset’s final decision.

As opposed to diplomatic initiatives, military strategy, and religion, this is the matter on which the result of this election has the potential to alter the very fabric of Israel’s democracy. In the days leading up to the April election, Netanyahu reiterated on record that he would not be promoting any personal legislation with the intention of thwarting the legal process against him for three cases of corruption. Yet, after the election during the coalition talks, Likud promoted this issue to the top of its agenda with other parties.

This brings to light the larger idea of ridding the Supreme Court of its ability to strike down administrative decisions or laws made by the Knesset via the override clause that exists as a passage of legislation right now. The nixing of this clause would limit the Supreme Court’s authority in exercising judicial oversight over the government. Yet, it has many proponents, especially among politicians who are looking for new ways to escape their personal legal messes. Furthermore, there are also additional proposals to politicize the appointment of judges, altering the process by which governmental legal advisors are appointed, and other similar moves that can dramatically reduce the scope of judicial review of other governmental institutions in the country. Such proposals could cause irreversible damage to Israeli law enforcement agencies, and moreover, would remove the one effective and meaningful method by which political power is checked and individual and minority rights are guaranteed in a country that has no bill of rights or constitution.

Apart from this, minority rights also seem to be the ‘make or break’ of this election. Until now, for Netanyahu, the public’s focus on security and economy has led to better results for him, but as the focus shifts to civil issues especially relating to the state and religion, the centre-left seems to growing. This is because Gantz has emerged as the anti-Netanyahu who promises to represent unheard voices. The Arab voter turnout in the September election was 60-61 percent, which is a massive jump even from April, which saw only 45 percent of the Arab populace coming out to vote. Hence, in almost thirty years, this is the first time that real cooperation may emerge between Arab representatives in Israel and the largest party in the Knesset. Martin Indyk attributes this to the fact that in recent years, Arab minorities have become disillusioned with the issue of Palestine and that they have begun to focus more on issues of self and community like community policing and education, thereby engaging with the political process in a different way.

Source: BBC

On Sunday, September 22, the Joint List of Arab parties announced that they will be backing Gantz, and this, doubled with the support of the Labour party, puts the BW in a comfortable lead against Netanyahu with 57 seats, which is the highest coalition that a centre-left party has been able to make in the past ten years. There is a slim likelihood of Gantz being able to garner the remaining number of seats to create a majority, as the YB is yet to decide whom to ally with. The possibility of a unity government seems most likely, as Lieberman has maintained that he will only sit in a coalition that includes both, the BW and Likud. Gantz is also rigidly stuck to the stance that if a unity government does arise, he will not consent to the coalition until King Bibi is booted out. Lieberman’s final decision, therefore, is crucial, as his alliance would set his own position in stone as either a ‘kingmaker’ or a ‘kingslayer’ if he chooses to side with Netanyahu or Gantz respectively.

What about Israel's international relations?

In the West Asian region, Israel is surrounded by different problematic situations; in Gaza, of course, and also Lebanon, Syria, and Iran. This has been a major issue under Netanyahu’s leadership, but there is a general consensus among Israeli public and intellectual circles that he has handled it fairly well so far, barring the last few weeks of airstrikes. One may assume that Gantz, due to his centre-left position, would have a different approach to security and foreign policy. However, BW leadership has three former chiefs of staff — Gabi Ashkenazi, Bogie Ya’alon, and Gantz himself. All three individuals have deep experience and credentials in security, so Israel’s approach to the field will definitely be in good hands, but it may not reflect drastic changes after all. It has been opined by experts that a Gantz-led administration would see a strong level of continuity from Netanyahu in terms of foreign security issues.

The fundamental difference between Gantz and Netanyahu, then, is that Gantz is much more supportive of a separation between Israelis and Palestinians. This does not mean that at this moment he is in favour of a two-state solution or an independent Palestinian state, but definitely supports a separation from the Palestinians unlike King Bibi’s coalition of settlers and right-wing supporters. One is yet to see a manifesto that fully details what such a separation would entail. On the other hand, Netanyahu vowed that if re-elected, he would definitely annex the West Bank. Presently, he does not have the authority to implement such a policy, and if a unity government is set in place, he will be forced to join in the BW’s more centrist approach to the Palestinian issue. Annexing the West Bank, then, would be impossible; however, Gantz has also maintained that areas like the Jordan Valley and other major settlement blocs should remain under Israeli control.

With respect to other countries, Israel’s relationship has usually moved farther and deeper than any individual personalities. Donald Trump has, time and again, used the US-Israeli bond as a means to serve his political ends, particularly to garner support among Evangelicals and Orthodox Jews, since American Jews have been traditionally very supportive of the Democratic Party. Furthermore, Israel is crucial to Trump’s Iran policy as well as his war on extremism. Israel’s policy towards Iran and its proxies is highly unlikely to change. The back and forth of violent airstrikes and rocket fires between the Hamas and Israel is also likely to continue, but not allowing the situation to escalate so much that Trump’s “Deal of the Century” is jeopardized. The US President has also been a big supporter of Netanyahu, since the latter is loved and admired immensely among American Evangelical communities. But Trump “hates losers” and does not like associating with them, and given his track record with loyalty and promises made to world leaders, it seems that he is backing away from his support for Bibi. Since the Israeli relationship is so crucial to his own reelection, Indyk argues, Trump will embrace whichever Prime Minister or government wins this election.

Indo-Israel relations have improved drastically since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office, and a heavily documented personal relationship between Modi and Bibi including regular visits has been a strong foundation on which bilateral ties have been strengthened. The Modi-Bibi alliance is so strong that Modi’s face was featured as a part of Netanyahu’s campaign. Moreover, this relationship pushed India to uncharacteristically vote against Palestine at the UN Economic and Social Council. The two states have eased visa restrictions for one another, and there has been a revamp of technical cooperation on irrigation, water supply projects, and agriculture. This closeness of the two world leaders, however, has raised doubts that this partnership is one between political parties and their personalities rather than two states. But Modi’s cult of personality is at its peak, and for him to retain his image as a development-oriented leader, it seems likely that his public relations team will paint him as a close friend to Gantz, too, if required.

Keeping all these factors in mind, it is not very likely Israel’s external dimensions will incur significant changes with a change in leadership, especially with the very real possibility of a unity government headed by Gantz. A win for Netanyahu, however, will see a more rigid stance towards the Palestinian issue and may increase hostility with Iran and its proxies. But whoever takes office will definitely alter the country’s democratic fabric in many ways, socio-politically and structurally. Media houses all over the world are celebrating the end of Netanyahu's regime, but official results are still pending as the state waits for Lieberman to take a side. If Gantz assumes office, his biggest challenges will be to maintain transparency in the system and fulfil his promise of uplifting minorities. If Netanyahu gets his way, neither of these will be on the agenda. One hopes that this election reaches some end and does not move into a third iteration; else, the biggest loser to come out of this whole exercise will be the Israeli democratic system itself.

References

Avraham, R. (2019). What Israeli foreign policy changes can we expect following the 2019 elections? - Foreign Policy Blogs. Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2019/09/20/what-israeli-foreign-policy-changes-can-we-expect-following-the-2019-elections/

Beauchamp, Z. (2019). Israel’s election, and how Benjamin Netanyahu might lose, explained. Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://www.vox.com/world/2019/9/17/20869050/israel-election-results-netanyahu-jordan-valley-democracy

Blarel, N. (2019). India and Israel: A tale of two elections | ORF. Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/india-and-israel-a-tale-of-two-elections-55353/

Burton, G. (2018). Explaining India’s Position on Jerusalem and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://www.mei.edu/publications/explaining-indias-position-jerusalem-and-israeli-palestinian-conflict

Cook, S. (2019). Israel’s Elections: What to Know. Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/israels-elections-what-know

Explained: Israel’s parliamentary elections. (2019). Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://gulfnews.com/world/mena/explained-israels-parliamentary-elections-1.66477977

India embraces Israel in unprecedented anti-Palestine vote at the UN. (2019). Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190612-india-embraces-israel-in-unprecedented-anti-palestine-vote-at-the-un/

Indyk, M., & Ravid, B. (2019). Crossing the Rubicon? Understanding the Implications of Israel’s Elections [In person]. Conference Call, Council on Foreign Relations.

Jordan Valley will always remain under Israeli control, Gantz vows. (2019). Retrieved 23 September 2019, from https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-jordan-valley-will-always-remain-under-israeli-control-gantz-vows-1.7609452

Image Credit: KCUR 89.3