On December 19, Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang remarked that he was both “honored” and “disappointed” to be the only non-White candidate on stage for the 6th Democratic debate. Senator Kamala Harris dropped out of the race a few weeks earlier, and Senator Cory Booker was not polling highly enough to qualify for a place on the stage.

In a sense, this leaves Yang as the sole voice of people of color (POC) in the presidential race. Even assuming that he possesses the credentials to be a quality president, how can Yang engender solidarity among POC when there is no unity amongst them, both in the United States (US) and globally?

Using a Marxist approach to race relations, it can be surmised that over at least the last 700 or so years, POC have been an oppressed underclass in a world dominated by White overlords, who control the means of production.

However, haphazardly clustering all POC together ignores social hierarchies that bestow varying levels of social power and mobility to different racial groups.

Moreover, it ignores inter-POC racism, wherein those POC at the semi-periphery of power do the bidding of the Whites so as to maintain their position of relative power over those POC at the absolute periphery of power.

For instance, Asian Americans are seen as a ‘model minority’. They form just 5% of the US population, but 12% of the workforce. They also boast higher levels of education, income, and homeownership than the average population, particularly compared to other groups of POC. Their success is used to further the myth that systemic racism is either non-existent or an insignificant hurdle in achieving parity with the White population.

Asian Americans are thus used as agents of White supremacy, thereby stratifying discrimination against African Americans. Asian success is used to perpetuate the myths that Black failure is a result of laziness and a natural predisposition to crime, rather than systemic racism.

In order to solidify their newfound status of economic parity with Whites and elevated position in the social hierarchy, Asian Americans perpetuate these same stereotypes and attempt to distance themselves from being seen in the same light as African Americans.

For example, in August 2018, New York mayor Bill de Blasio proposed scrapping entrance exams for the city’s elite public high schools. De Blasio posited that under-represented communities, such as African Americans and Latinos, are not able to escape poverty because they can’t afford the same level of tutoring and test preparation tools as their Asian American counterparts.

Currently, Asian Americans represent 16% of New York’s student body, but hold 60% of seats in the city's elite public high schools, compared to just 4% for African Americans, and 6% for Latinos. Yet, in all other New York high schools, Black and Latino students form a combined 72% of the student body.

Therefore, de Blasio suggested that admissions to these elite high schools be based solely on school performance and state-wide exam scores; he estimated that this would result in 44% of admissions being offered to African Americans and Latinos. However, de Blasio’s affirmative action proposal was met with stern reprisal from the Asian American community, who took to the streets in protest. They argued that it would reduce the quality of education by forcing more academically-gifted students to share classrooms with ‘less intelligent’ students.

However, De Blasio’s proposal did not remove merit-based admissions. It only suggested using the existing state exam to determine a candidate’s meritoriousness rather than a specialized exam requiring additional financial investment in tutoring and preparation. Therefore, Asian American protests seem more rooted in the potential changes to the racial demographics of the student body, rather than the intelligence of it.

White under-representation in these elite high schools is less of an issue, because, by virtue of their race, this does not preclude them from future employment opportunities. However, Asian American opposition to affirmative action presents significant obstacles to African American and Latino communities achieving racial and income equality.

This gives rise to the ‘middleman minority’ theory. Middlemen minorities, while possibly suffering discrimination, do not hold an “extreme subordinate” status in society. This leads to a situation in which middlemen both cement White supremacy and crystalize the subordination of groups positioned lower than them in the social hierarchy.

Blame for such attitudes cannot be placed solely at the feet of White-dominant countries; this mindset is prevalent across the world and is even carried over from POC’s countries of origin. For example, Asian Americans & Pacific Islanders (AAPI) data illustrates a 40% decrease–from 80%–in Chinese American acceptance of affirmative action for Black students and other minorities from 2012 to 2016. This is attributed to an influx of Chinese Americans who were born abroad.

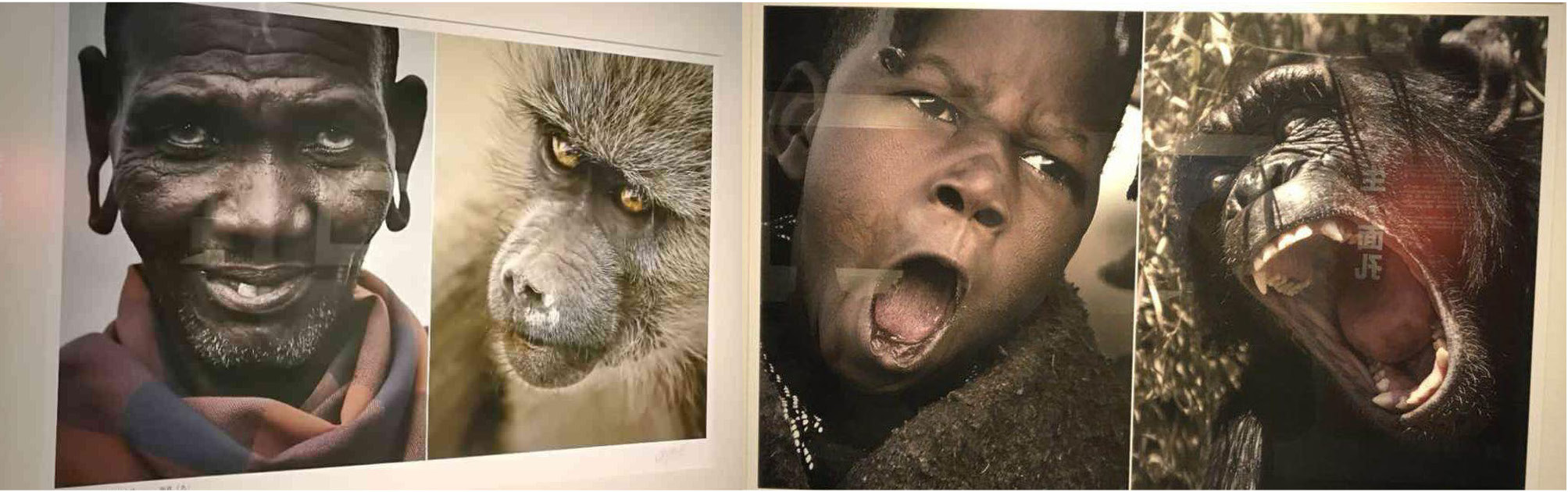

These biases migrate from countries where such prejudices are proudly displayed. In 2014, a museum in China held an exhibit labeled ‘This is Africa’, in which it placed the images of Black Africans, including children, alongside pictures of animals. Although the exhibit was eventually taken down after multiple complaints from African commentators, it was visited by over 141,000 people.

Nevertheless, Asian Americans are not alone in abusing their position of relative power and agency.

Although Latinos in the US are far from being a model minority, they still hold a position of relative structural superiority to African Americans. A 2008 Pew Research Center report suggests that while 70% of Blacks say the two communities get along, only 57% of Latinos say the same; Latinos are also 12% more likely to say inter-community relations are strained. Similarly, Latinos aligned more closely with the Whites than African Americans in their perceptions on the prevalence of systemic racism; statistics show that they are unconvinced about whether Blacks face discrimination in "applying for a job, buying a house or renting an apartment, applying to college, [and] shopping or dining out".

While such opinions are not themselves indicative of intra-POC racism, it is vital to note the treatment of darker-skinned citizens in Mexico. Mexico has an incredibly diverse racial ancestry, including Spanish, African, and Indigenous influences. Today, over 53% of the population identifies as mestizo, or mixed-race. However, a 2017 Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) report notes that Mexicans with the lightest skin, who typically have greater European and Indigenous ancestry, complete an average of 10 years of schooling versus just 6.5 for Mexicans with the darkest skin, who have greater African ancestry. Darker-skinned citizens also earn 41.5% less income than their lighter-skinned counterparts. In spite of such damning statistics, a 2010 national survey on discrimination found that Mexicans believe that age, gender, and social class have a greater impact on such figures than race.

Similar trends are observed across Latin America, such as in Ecuador and Brazil.

Light-skinned Mexicans may dismiss the impact or relevance of systemic racism as it does not impact them as heavily as their darker-skinned counterparts, similar to what Latinos report about African Americans in the US. It is clear that they transport these biases across the southern border and serve as tools of White supremacy, just like Asian Americans.

The global impacts of these beliefs hold both historical and contemporary relevance.

Under South Africa’s apartheid system, social hierarchy placed Whites at the top, ‘Coloureds’ and Asians in the middle, and Blacks last. Apartheid was abolished in 1994, yet these divisions still exist. Discrimination by Whites is heavily documented; however, the complicity of South Africa’s secondary class over its tertiary class is less discussed.

Coloreds and Asians are an intermediate group between Whites and Blacks in South Africa, and benefit from their proximity to Whites through better “employment, educational, and housing opportunities than Blacks”.

This discrepancy is not only selective bias by the dominant White population, but also a result of many Coloureds and Asians attempting to ‘whiten’ themselves. During the Apartheid era, several Coloureds and Asians applied to obtain “pass-White” status through the Population and Registration Act, whereby they would be legally reclassified as White. It is telling that when Coloureds and Asians were given the opportunity to distance themselves from Blacks, many chose to do so. Moreover, it reinforced power imbalances as Coloureds and Asians had the privilege of choosing their race, while Blacks were not offered the same social mobility.

Despite the abolishment of this provision following the end of Apartheid, the repercussions from it are still felt today. Blacks form 80.9% of the population, Coloureds 8.8%, Whites 7.8%, and Asians 2.5%. Yet, In 2001, unemployment figures stood as follows: 50% for Blacks, 20% for Coloureds, 17% for Indians, and just 6% for Whites. Although Black unemployment decreased to 39% by 2015, they are predominantly and disproportionately represented in the low-skilled employment sector. Consequently, similar inequalities are observed in poverty statistics.

Similarly, Mahatma Gandhi once said that part of India’s independence struggle was convincing the British that Indians were being “degraded” by being treated the same as Black Africans. Even today, African tourists, students, and workers report feeling highly unsafe in India. They are frequently victims of mob violence, with ‘vigilantes’ spuriously claiming that it is punishment for selling drugs and indulging in criminal activities. Likewise, the country’s Siddi community, descended from the Bantu peoples of East Africa, are frequently denied land rights despite providing sufficient documentation. For example, in Uttara Kannada, only 137 of their claims have been approved out of the 2,300 submitted. They are also often arrested without evidence, charged as ‘thieves’ under false pretenses.

In fact, some of these biases even predate the ongoing era of White dominance. Between AD 650 and the 1800s, Arab slave traders sold almost 10 million Africans to Arabia and the Indian subcontinent. Several Siddis were actually brought to India as indentured servants and slaves. The Arabic word abeed, meaning slave, is still used to describe Black people in Algeria and Yemen.

Hence, considering the nature of their historical and contemporary interactions, is solidarity between POC realistic? By viewing power as a zero-sum game, the middlemen groups have actively sought to increase their agency at the expense of those at the periphery of power. Rather than trying to disestablish entrenched systems of White supremacy in unity with other POC, they have instead further solidified White dominance and reach.

Whites form a minority of the world’s population but hold a grossly disproportionate amount of its power and wealth. Thus, the continuation of White hegemony is dependent on disharmony amongst POC, who make up the majority of the global population.

So long as the middlemen groups of POC continue to step on those at the lower end of the racial hierarchy to achieve upward mobility, rather than fighting alongside each other to dismantle a hierarchical system, a shift in the status quo remains a distant dream.