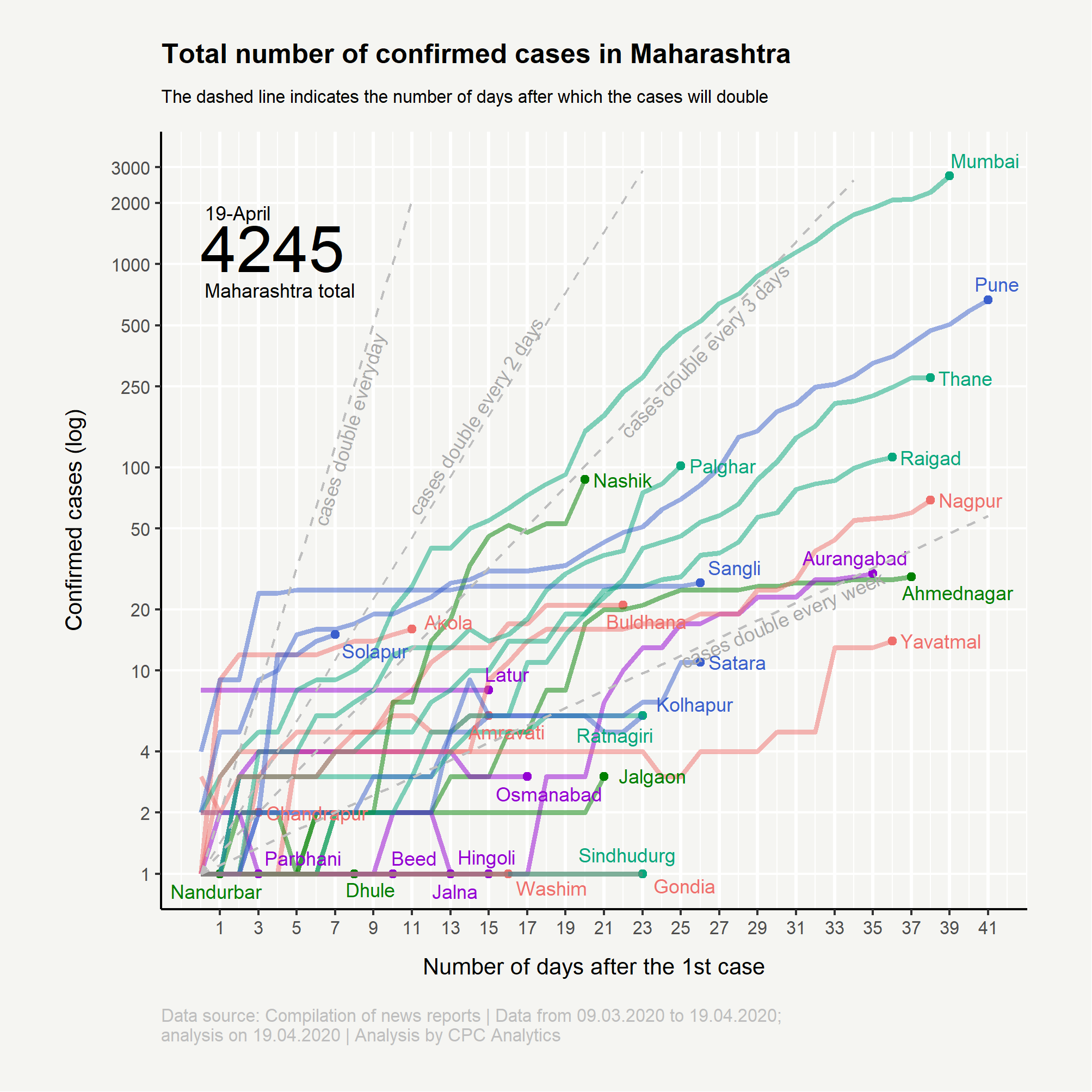

On Sunday, Maharashtra became the country’s first state to cross the 4,000 mark after it reported 552 new cases of the coronavirus, its largest daily increase by far. According to State Health officials, this spike in cases now takes the state’s tally of positive coronavirus cases to 4,200. Additionally, in a press statement, the Public Health Department said there were 12 COVID-19-related deaths in the state on Sunday, which raised the state’s death toll to 223.

But despite such a high number of cases and a steady daily increase of deaths due to the deadly virus, the state government’s efforts have been lauded by many as a model for others to follow. From Bollywood celebrities to public figures, the handling of various facets of the crisis by Maharashtra’s political leaders and the ruling coalition has received praise; so much so, that Maharashtra’s response has been compared to other states who have been able to control the spread of the virus and flatten the curve.

However, with the highest number of fatalities and the highest number of cases in the country, it would be unfair to shower praises on the Maharashtra state government or put it in the same company as states like Kerala.

For instance, on the 15th of April, 45% of deaths that occurred in the country were from Maharashtra. Numbers on Sunday show that out of the 31 deaths reported yesterday across the entire country, twelve were from Maharashtra alone.

According to state health officials, the reason for such a massive rise in numbers and a large number of overall cases is its aggressive testing policy, contact tracing, and the natural course of progression that this disease follows. To be fair, the state has tested more people than any other state in the country. Nevertheless, upon comparing all the Indian states which have conducted a minimum of 5000 tests, the number of tests done to detect one positive case in Maharashtra is 17. In Chhattisgarh, it is 153, in Odisha 126, in Bihar 111, in Karnataka 49, in Kerala in 45, in Haryana 40, and in Rajasthan 40. Only Madhya Pradesh and Delhi perform worse along this parameter, averaging 16 and 13 tests, respectively. Similarly, when you see the tests per million (TPM) data, Maharashtra lags behind most of the bigger states where there are a large number of cases. This illustrates that a resident of Maharashtra is more likely to have the coronavirus, indicating that the virus is not being adequately contained.

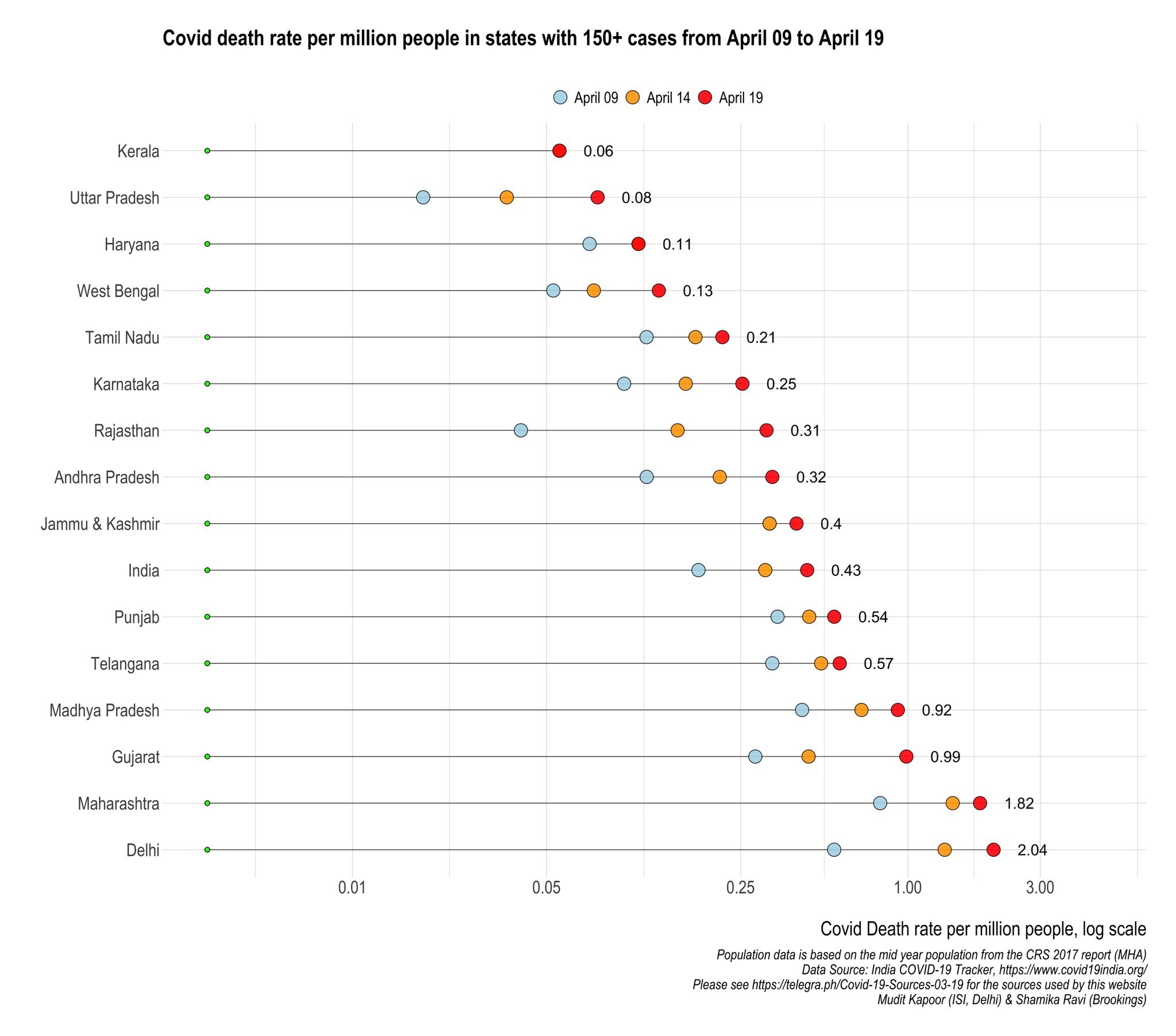

Moreover, the optimism espoused by Maharashtra’s leaders following the state’s doubling rate of the disease decreasing to 5.5 days from 3.5 days was washed away following Sunday’s spike in new cases. In fact, the state makes up for almost 50% of the total number of fatalities in the country, with a mortality rate of 6-7%, which is almost double the national average of around 2.8-3% and over the global average of 4-5%. In comparison, Kerala, which is mistakenly mentioned in the same breath as Maharashtra, has a mortality rate of just 0.58%.

The graphic below, which gauges the COVID-19 deaths per million in states with more than 150 cases from April 09 to 19 depicts that Maharashtra is one of the worst-performing states in the country, with only Delhi doing worse.

The general rule of thumb indicates that that the higher the mortality rate, the higher the spread of the disease in that region. Thus, while Maharashtra is admittedly testing more than other states, this ignores the fact that this level of testing is necessitated by the disproportionately high number of cases in the state. The state accounts for almost a quarter of the cases in the country, giving it no option but to scale-up testing.

The general rule of thumb indicates that that the higher the mortality rate, the higher the spread of the disease in that region. Thus, while Maharashtra is admittedly testing more than other states, this ignores the fact that this level of testing is necessitated by the disproportionately high number of cases in the state. The state accounts for almost a quarter of the cases in the country, giving it no option but to scale-up testing.

The level of testing and cases are sure to rise as the coronavirus spread through Mumbai, one of the country’s most densely populated regions. On Sunday, Mumbai alone reported 456 new COVID-19 cases, the highest-ever single-day spike. Of the 4,200 cases in the state, 2,724 cases are from Mumbai alone, with the virus now rapidly spreading in the slums of Dharavi and Govandi. These densely populated areas, where 78% of toilets do not even have reliable water supply, will likely soon become hotspots for the virus.

More worrying still, is the fact that the civic body has revised its testing formula thrice just in this month alone, demonstrating a lack of a coherent strategy and an understanding of the severity of the situation. For example, earlier this month, the Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC) thankfully walked back on an incomprehensible new policy under which high-risk contacts of COVID-19 patients who are asymptomatic would no longer be tested. However, despite dropping the ill-advised policy, even now, hospitals will only test asymptomatic cases five days after they come in contact with people who test positive. Hundreds of high and low-risk asymptomatic contacts quarantined at the BMC-controlled facilities have been released and asked to self-quarantine at home, posing a danger to the communities they return to. Given that the Chief Minister has said that 70% of COVID-19 patients in the state are asymptomatic, perhaps more attention must be paid to such cases, with a greater emphasis on preventative measures.

Additionally, healthcare workers have been instructed to wait for people to turn up at fever clinics installed at locations where clusters of cases have been reported, which is indicative of a delayed response. In fact, the Chief Minister himself has accepted that “many people have reported [symptoms] in the last stage”, by which point they might have already contributed to creating a whole new cluster.

Such incidents have prompted the Thane district and the Pune Municipal Corporation, to declare containment zones. In fact, there are currently 368 active containment zones in the state. The concern demonstrated by these areas indicates the level of the spread of the virus and how the state government has not adequately grasped the severity of the situation.

The state government’s response and strategy in handling the migrant labourer crisis has been equally lacklustre. The massive crowd outside that gathered outside Bandra station on 14 April, and the subsequent clashes with the police suggest that the authorities are not addressing their concerns or delivering their needs. On the other hand, Kerala, which also saw similar protests in March, managed to assuage fears and discontent by taking care of workers’ needs with a more humane approach. For instance, the Kerala government tied up with a service provider to recharge migrant workers’ phones for Rs. 100-200 a month to ensure that they remain in touch with their families back home. In addition, it is also providing them with three meals per day, with some authorities going as far as giving refreshments and even altering the meals in some places to accommodate varying palates and dietary restrictions. Along with such measures, the government has also attempted to shift the negative and othering narrative by classifying them as “guest workers”, rather than migrant workers.

Maharashtra, which has one the highest number of migrant workers, is still in third place in terms of relief centres, with only 1,135 centres. It was only after the clash at Bandra station that the government announced giving Rs 2,000 in assistance to 12 lakh construction workers and decided to allow over one lakh migrant sugarcane workers to return to their native villages within the state. Although a welcome decision, these measures could have come much earlier as they were not dependent on the Central government’s help or discretion. Bus services, for instance, are not centrally operated, and could be been used to send at least native workers to different parts of the state. While the state leaders have rightfully criticised the Central government’s lack of strategy when it comes to either anticipating or solving the migrant crisis, the state authorities, too, are guilty of a delayed response.

Therefore, while the Chief Minister merits some appreciation for his regular media interactions and Maharashtra’s heightened level of testing, this does not make up for the state’s inability to contain the virus, truly understand the seriousness of the state’s precarious position, or address the concerns of hundreds of migrant workers in a timely fashion. At this juncture, a good communication strategy and efficient public messaging are desirable, but they aren't enough and shouldn't be considered as a solution or strategy by itself. Hence, while there are commendable aspects to the state’s leadership, these are not sufficient to merit Maharashtra being placed in the company of states such as Kerala, which have contained the spread of the virus and addressed the concerns of their people and migrant workers before it escalated to the point of disaster.

Image Source: Office of Uddhav Thackeray (Twitter)