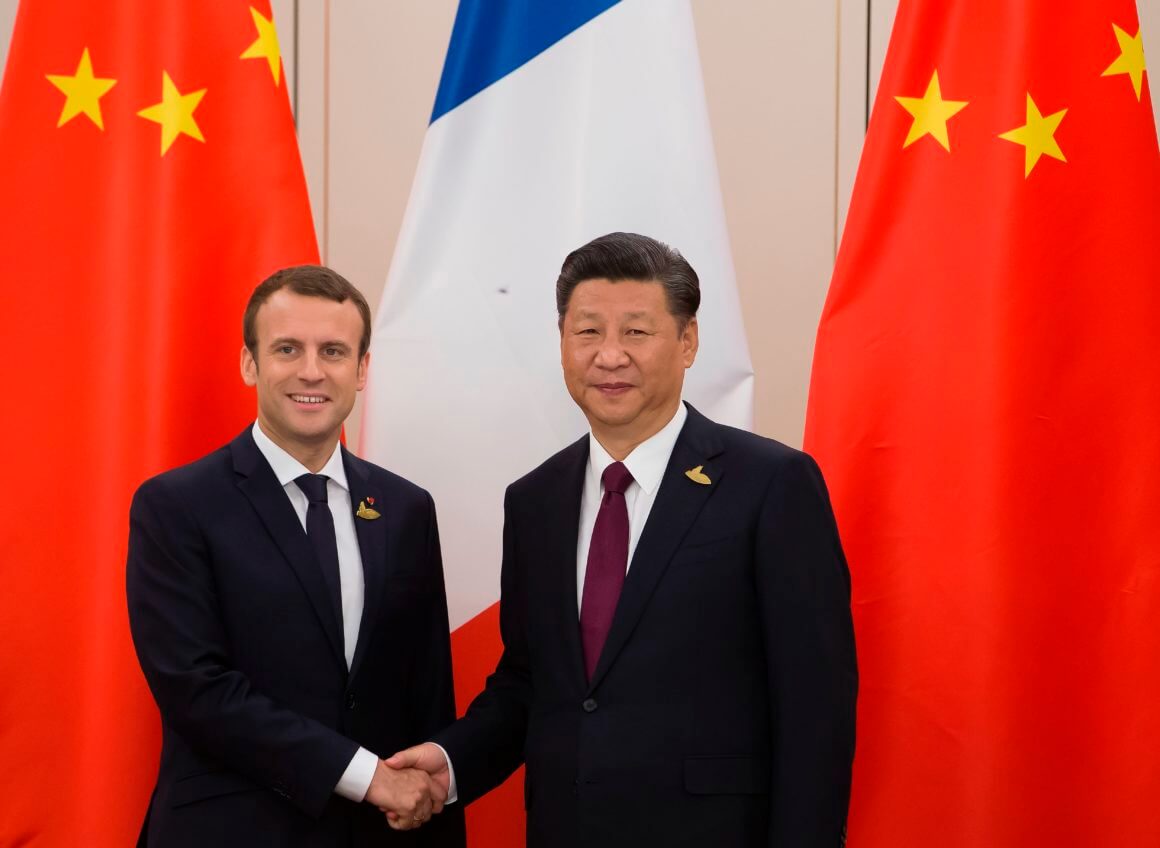

Last Thursday, President Emmanuel Macron announced that France will not join the diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics because doing so would be “insignificant” and merely “symbolic.” The French leader said he would instead work with the International Olympic Committee to ensure the protection of athletes, citing the recent international furore over the safety of Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai. Although he did not elaborate on the strategy, Macron reasoned, “You either have a complete boycott, and not send athletes, or you try to change things with useful actions.”

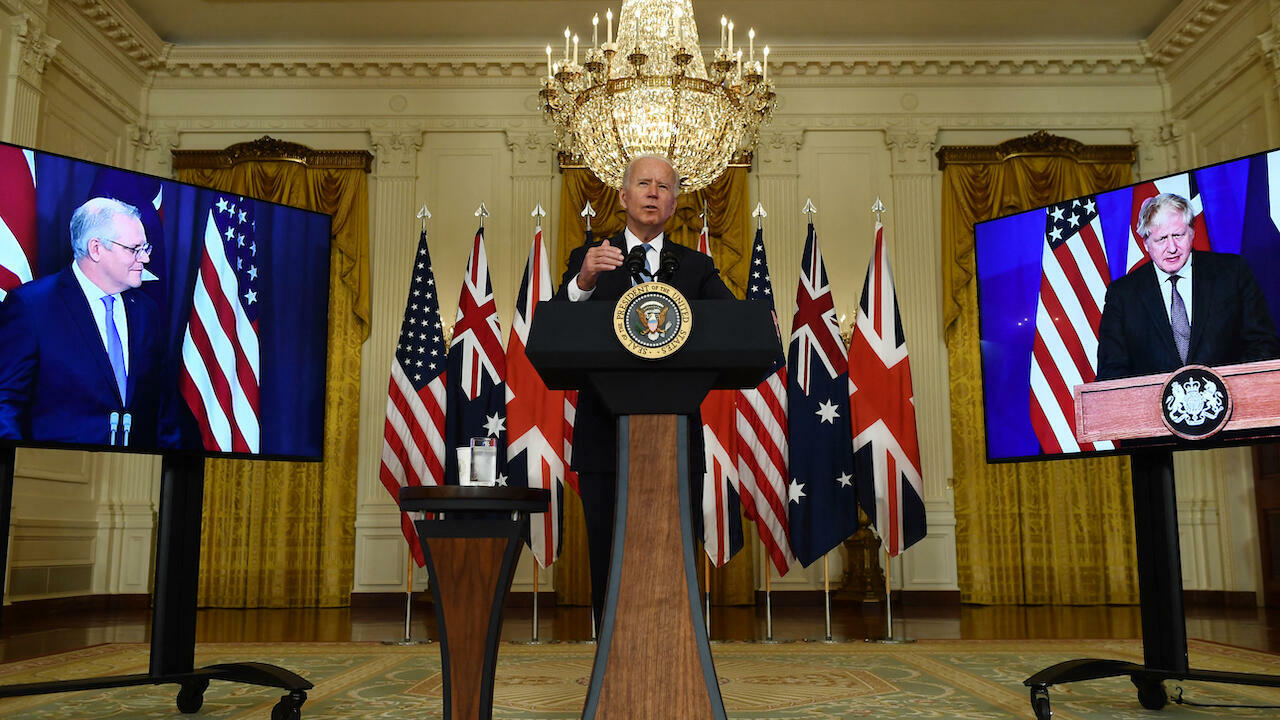

Macron’s stance is in stark contrast to that of typical Western allies like the United States (US), Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, and New Zealand, which all announced a diplomatic boycott of the Games. In this respect, France’s non-alignment came as somewhat of a surprise, as it has in the past mirrored the foreign policy actions of its partners, especially vis-à-vis China. It has repeatedly called Beijing out over its human rights abuses and responded with sanctions. Likewise, it has continued to broaden its role and ties in the Indo-Pacific to help counter China’s maritime aggression. So, why were the Olympics any different?

Part of the answer may lie in the fact that Paris is hosting the 2024 Summer Olympics. France may not want to undermine its showpiece event by making it a diplomatic battleground, considering that the Olympics are considered a source of great national pride, geopolitical influence, and economic resources. It stands to reason that France would want to avoid the 2024 Olympics becoming another means to divide countries along political and ideological lines, whereby Western countries stand with one another against Russia, China, Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, and their growing list of allies. Doing so would endanger tourism, trade, new employment, and infrastructure.

Aside from not wanting to imperil the economic dividends of hosting the Olympics and its position as a neutral global actor, France’s unwillingness to join the US-led diplomatic boycott may also indicate its desire to broaden its relationships in a post-AUKUS world. In September, tensions with long-term allies Australia the US dramatically escalated after Australia abandoned its $65 billion traditional submarine purchasing deal with France in favour of the AUKUS nuclear submarine development deal with the US and the UK. French officials described the sabotage of their deal as a “stab in the back” and briefly recalled its ambassadors from the US and Australia.

In the eventual fallout with AUKUS members, France has looked to sign defence deals with Greece, Indonesia, and India. Moreover, despite eventually sending its ambassadors back to Australia and the US, it is clear that the Macron administration is not over what happened. Last week, its ambassador for the Indo-Pacific, Christophe Penot, said that there remains a trust deficit with Australia, which he said is still “in denial” about how badly it handled the communication of the AUKUS decision.

At the same time, however, France has sought to carve out an independent foreign policy from its wartime partners for a while now, regardless of the 2024 Olympics and the AUKUS row.

For instance, in March 2011, it was French forces who first initiated the intervention in Libya. Under then-President Nicolas Sarkozy, France was among the most enthusiastic backers of a United Nations Security Council resolution that supported a military intervention in Libya. Other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), a military alliance that includes the US, only unwillingly followed France’s lead afterwards. Furthermore, in the present day, while the United Nations, NATO and other Western actors back the Government of National Accord led by Fayez al-Sarraj, France has steadfastly supported rebel warlord Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army, who enjoys the support of countries such as Egypt, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, none of which can easily be described as Western allies, particularly Russia.

France’s desire for independence from its Transatlantic ally has been evident in other arenas as well. Macron has on several occasions insisted that Europe needs to take more responsibility for its own security, instead of being dependent on the US. This view was also shared by former US President Donald Trump, who frequently called on NATO members to share a greater part of the “burden” of their own security as part of a wider isolationist approach under the now-former administration.

Macron cemented his goal of independence at the Munich Security Conference in February, when Joe Biden announced Washington’s return to multilateralism by saying: “America is back. The transatlantic alliance is back” and that Europe and the US must once again “trust in one another.” When it was Macron’s turn to address the event, he directly contradicted Biden’s aspirations of working together on security matters. “I listened to President Biden… and appreciated the list of “common challenges. But we have an agenda that is unique,” Macron responded.

He stressed that Europe should not always require or rely on US participation or permission, especially for military actions on Europe’s borders with the Middle East and North Africa. “We need more of Europe to deal with our neighbourhood…I think it is time for us to take much more of the burden for our own protection,” Macron declared. While the general theme centred around Europe gaining financial independence in security operations, it was also clear that he hopes that reduced financial dependence on the US will pave to way for Europe to have greater agency.

In this respect, the AUKUS deal and the ensuing fallout only made France even more certain about the necessity of paving its own path, particularly now that it has become aware that countries whom it considers partners and allies could unexpectedly turn their backs on a whim and sabotage Paris’ core interests. That being said, perhaps Macron’s comments can also be taken at face value, considering that China has already said that “nobody cares” if the boycotting countries’ officials show up or not. The pressure exerted by a diplomatic boycott of the Games will be minimal and is highly unlikely to result in any change of course from China. In this respect, perhaps the larger story is whether the US and its allies can regain France’s trust or whether claims of a seismic rift are being overstated.