Earlier this month, Bangladeshi and India signed a water-sharing and management treaty on the Kushiara river, the first such transboundary river management deal since the 1996 Ganga River management agreement. Bangladeshi Prime Minister (PM) Sheikh Hasina expressed hope that the agreement would provide the necessary impetus to resolve the decades-long Teesta water dispute as well.

In total, India and Bangladesh share 54 rivers. Given that India holds a majority of the water in 43 rivers, successive governments in Bangladesh have pushed for water-sharing mechanisms. The Teesta River dispute, though, has been particularly intractable.

Even though inter-state water sharing falls under the ambit of the central government’s powers in India, state-level politicians have obstructed any attempts to reach an agreement.

Earlier today, I had excellent discussions with PM Sheikh Hasina in New Delhi. Bangladesh is a major trade and development partner of India. We cherish the people-to-people linkages between our nations. During our talks we reviewed the full range of bilateral relations. pic.twitter.com/MYDEEcHtGK

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) September 6, 2022

Erstwhile PM Manmohan Singh facilitated an agreement in 2011 wherein India agreed to retain 42.5% of the water and allow Bangladesh to access 37.5% of the water during the lean season between December and March.

However, the treaty failed to materialise after West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee withdrew her support. She also blocked the Modi government’s efforts to resolve the issue in 2017, arguing that the Teesta River has no water to share. Since then, the dispute has been somewhat relegated to the back burner of India’s foreign policy considerations.

Admittedly, Mamata Banerjee’s concerns are not unfounded. According to a 2017 study, the flow of the Teesta River drops to 200 cumecs in February, which is insufficient to operate the Gazaldoba canal system in India and the Duani canal system in Bangladesh, which are respectively designed to withdraw 520 and 283 cumecs of water.

#WATCH: Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina speaks on West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee and Teesta issue,at India Foundation Awareness programme #Delhi pic.twitter.com/144LUEUje5

— ANI (@ANI) April 10, 2017

However, while the issue may not feature highly on India’s foreign policy objectives, it is a high-priority issue for Bangladesh, which is a lower riparian country.

The Teesta River flows through Sikkim to enter West Bengal, where it finally merges with the Brahmaputra in Assam and the Jamuna in Bangladesh. Running over 100 kilometres and directly impacting the lives of 21 million people, it is a critical source of water and irrigation in the Rangpur region of northwestern Bangladesh.

Despite their failure to reach an agreement, however, Hasina has proclaimed that India and Bangladesh have entered a “Sonali Adhyaya,” or a golden era, in bilateral relations. She has said on several occasions that India is Bangladesh’s “most important partner.” Similarly, Bangladeshi Foreign Minister (FM) Mustafa Kamal said earlier this month that economic crises like Sri Lanka will push countries to “think twice” about joining China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative.

The Hasina government has also been a critical partner in tackling cross-border Islamist militancy.

However, a continued failure to resolve the dispute may not only endanger India’s age-old diplomatic partnership with Bangladesh but also push Dhaka to look to Beijing, which could drastically change the geopolitical status quo in the region.

In fact, Bangladesh has already turned to China for water management assistance. In 2016, it signed a memorandum of understanding with Chinese state-owned company Power China to embank portions of the Teesta River. The deal seeks to create a single “manageable channel” that increases the region’s water management capacity by reducing loss from floods and riverbank erosion. Bangladesh will finance 15% of the $130 million project, while the remaining portion will be acquired via a Chinese loan.

Northern and Central #Bangladesh reel under floods as Jamuna and Teesta break 40 year old record of Water level.#BangladeshFloods

— All India Radio News (@airnewsalerts) July 19, 2019

Pic: Reuters/Stringer pic.twitter.com/UjQWxmua89

Given China’s history of debt-trap diplomacy and acquiring key natural resources and state infrastructure when debtors are unable to repay what they owe, India must keep an eye on Chinese encroachment, not just into Bangladesh but also into India.

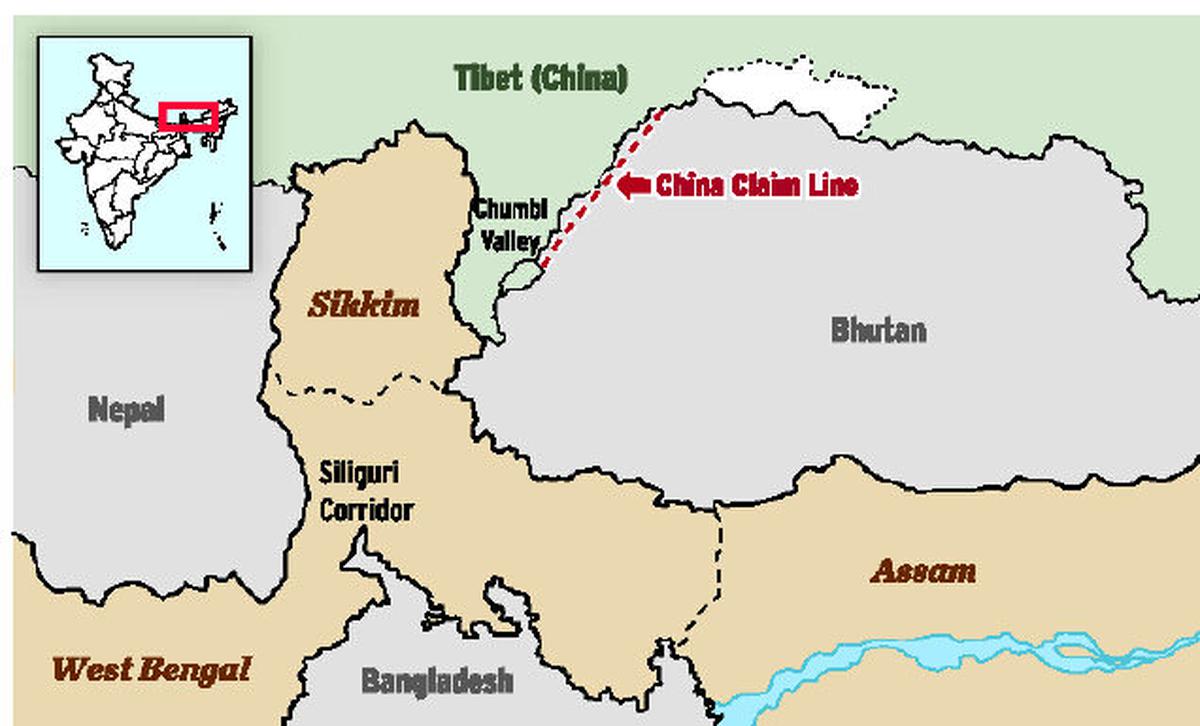

In fact, the Chinese Teesta project is situated close to the Siliguri corridor, a 22-kilometre-wide “chicken neck” connecting mainland India to its eight north-eastern states—Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Mizoram.

Geopolitical analysts refer to the Siliguri region as “the most vulnerable portion of India’s landmass,” given that it borders Bhutan, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

At the same time, there is also the threat of Hasina losing the election to Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh National Party (BNP) next year. The BNP is reportedly seeking an alliance with the far right and pro-Pakistan Jamaat-e-Islaami and is therefore even less likely to wait for India to come to a mutually agreeable solution. Crucially, it may even go out of its way to dismantle any existing cooperation with India on the Teesta River dispute.

After Hasina’s meeting with Modi this month, BNP Secretary-General Mirza Fakrul Islam Alamgir said the Bangladeshi PM had “sold the country” and criticised her “inability to deal with India.” Similarly, party spokesperson Asaduzzaman Ripon said Hasina’s failure to resolve the Teesta River Dispute had left the “whole nation disappointed.”

"Whenever I come to India, it's pleasure for me, especially because we always recall the contribution India has made during our liberation war," says Bangladesh PM Hasina pic.twitter.com/Xmi4AMzf1X

— Sidhant Sibal (@sidhant) September 6, 2022

Against this backdrop, Hasina, too, may be forced to expedite the Chinese project in order to secure a key foreign policy win ahead of the election.

With China creeping closer to the vulnerable Siliguri corridor, India must act now to resolve the Teesta River dispute by quickly addressing domestic roadblocks. Failure to do so would not only be a huge defeat in India’s ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and push a key ally into the arms of China but could also have far-reaching implications on national security and indeed territorial integrity.