In the global fight against the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, 326 million COVID-19 vaccines have been administered across the world through early-March. More than three-quarters of these doses were administered in just 10 nations, who cumulatively account for only 14% of the world’s population, but 60% of the global gross domestic product (GDP). This indicates that a handful of countries with high purchasing power parity are hoarding a majority of the world’s vaccine production, while less developed countries (LDCs) are struggling to protect their citizens. Consequently, while highly developed countries (HDCs) are edging closer to achieving pre-pandemic normalcy by next year, for LDCs and moderately developed countries (MDCs), who find themselves at the back of the procurement line, the disastrous economic and public health impacts of the pandemic could be extended for years to come. The prolonged economic impact of being mired in a public health crisis portends to further widen the already glaring wealth disparity between LDCs and HDCs. Therefore, for the benefit of the global populace, it becomes crucial to analyse how HDCs may be incentivised or pressured into making sure that the distribution is more equitable.

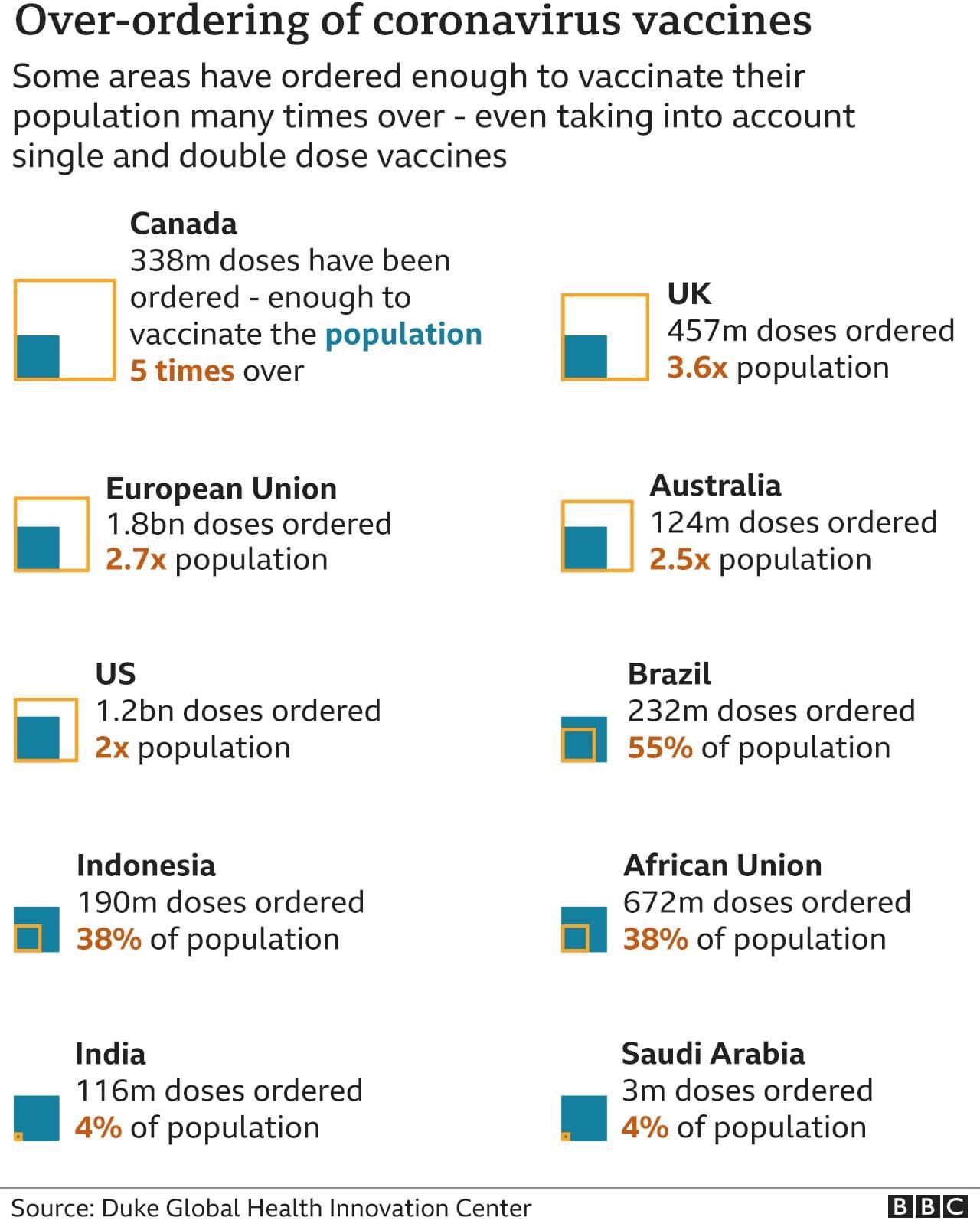

Several of these rich nations have enough capital to pre-purchase vaccines that can inoculate their entire population more than once. For example, according to a New York Times analysis done in December, the United States (US) has enough supplies to vaccinate its population about four times over. Similarly, Canada has ordered a total of 338 million doses, enough to vaccinate its population five times over. Likewise, the United Kingdom (UK) has ordered 457 million doses, which is enough to vaccinate its population by more than three and a half times. The European Union (EU) can inoculate almost three times its population with its order of 1.8 million doses, while Australia’s order of 124 million doses can inoculate its entire population two and a half times.

In sharp contrast, vaccination campaigns in the world’s poorest countries haven’t even seen the light of the day yet. Most of these nations are set to face almost another year of delays, as lucrative pre-order deals are giving the highest bidders priority manufacturing slots for 2021. According to an analysis by the People’s Vaccine Alliance, a group of organizations campaigning for the free and fair distribution of vaccines, 9 in 10 people in nearly 70 poorer countries are unlikely to be vaccinated at all this year. Indonesia, which has ordered 190 million doses, has enough to vaccinate only 38% of its population. In fact, according to a recent briefing by the Economist Intelligence Unit, most developing countries will not gain widespread access to COVID vaccines “before 2023 at the earliest.”

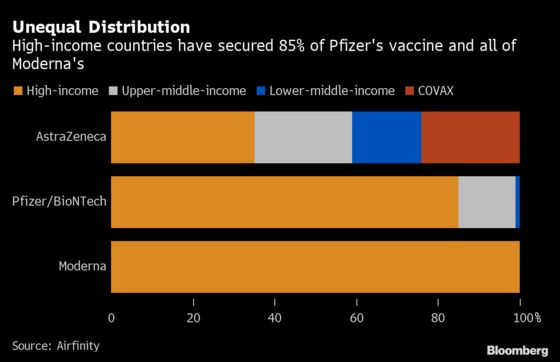

To put this in perspective, almost 190 nations have joined COVAX, the global initiative to equitably share vaccines. However, a handful of rich nations ended up buying 5.8 billion doses through direct deals with pharmaceutical firms, rather than through the COVAX pool. Since pharmaceutical companies have given preference to the highest bidders, which have been largely rich countries, the COVAX pool is also facing shortages. Therefore, although COVAX still expects to secure some two billion doses by the end of 2021, its efforts are being undercut by wealthy nations.

Unsurprisingly, the ongoing bidding war among countries has exacerbated vaccine shortages and raised the price per shot for poorer countries who were not able to make orders initially. For example, South Africa has been revealed to be paying nearly 2.5 times more than most European countries for a shot of the AstraZeneca vaccine. The potentially disastrous impacts of these shortages and price increases are amplified by the fact that the coronavirus still continues to rapidly spread and mutate into new, dangerous variants around the world.

Unfortunately, this cycle of new medicines “trickling down” to poorer countries only years after rich countries have reaped the benefits is a common theme with viral outbreaks. Promisingly, however, this time around, there have been growing calls from world leaders and humanitarian organisations like the United Nations (UN) to break the pattern.

For one, current vaccines stand the risk of losing efficacy against new variants of the virus that are mutating in countries where vaccination remains unequal. Therefore, there exists a possibility of the pandemic worsening in MDCs and LDCs and re-erupting in HDCs. For example, South Africa has already suspended the use of the AstraZeneca shot after the health ministry declared that it was ineffective against a new variant. Combined with this, the expiration date on the product itself makes hoarding irrational.

In addition to the fear of re-emergence, a recent study commissioned by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) argues that sharing vaccines with poorer countries is not just a moral obligation, but an economic incentive for rich countries as well. Since almost all economies are interconnected through trade, HDCs like Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, the UK, and the US could lose up to 3.9% of their GDP if a major part of the world remains unvaccinated. This is in great part due to the fact that consumers in unvaccinated countries will significantly lose their pre-pandemic spending power as the pandemic further strains their economies and results in greater unemployment and economic stagnation.

It has been calculated that hoarding vaccines could cost HDCs at least $4.5 trillion in lost income this year. This is substantiated by the fact that currently, the cost of fully funding the World Health Organization’s (WHO) programmes to deliver vaccines and treatments to developing countries is $27 billion away from its 2021 funding targets. The study predicts that this figure will be “dwarfed” by the cost of HDCs not sharing vaccines with the have-nots.

Further, the report also added that global supply chains (especially those involving construction material, car parts, and textiles) might be hugely disrupted. This is because these production chains, which represent up to 40% of international trade, are heavily reliant on LDCs and MDCs. Since these countries remain largely unvaccinated as of now, HDCs would end up bearing almost half the cost of this economic lull. In this sense, it becomes important for the self-interest of richer countries to pool resources for poorer countries to prevent the pandemic from becoming a zero-sum game.

Taking into account the interdependence of countries across the economic development spectrum in the global economy, the report concludes: “In the absence of global coordination, countries that successfully contain the virus will still struggle as long as the other countries do not contain it.”

Moreover, the equitable distribution of vaccines can yield more than just economic benefits, as evidenced by the soft-power influence gained by “vaccine diplomacy”. The greed-fuelled “vaccine nationalism” of rich, Western countries has created space for rising powers like India, competing powers like China, and resurgent powers like Russia to expand their diplomatic footprint. For example, while several countries have prioritised national programmes, Oxford and AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish company, made their know-how available to the Serum Institute of India. In turn, 23 million vaccine doses were donated by India to over 20 LDCs, which were prominently branded as a “gift from the people and government of India.” Likewise, China and Russia have also been competing for influence in the sphere to reap dividends in the long-term by signing deals with Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Indonesia to manufacture their nationally developed vaccines locally. According to Reuters, China has so far committed to providing at least 463 million doses of its home-made COVID-19 vaccines. Similarly, Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine has been officially authorised in 46 countries as of March.

Though COVAX remains powerless in terms of making it mandatory for individual governments to share their vaccine surpluses, some HDCs have independently taken the initiative to do so for a mix of moral, financial, and diplomatic reasons. Norway, which has purchased three times as many vaccines as it needs, has announced that it will be redistributing its excess doses to other countries through the COVAX initiative. Norway’s minister of international development, Dag-Inge Ulstein, said that the reason was not just morally motivated but also in the country’s own self-interest, noting, “...it will be a long time before these countries are able to vaccinate a sufficiently large proportion of their populations. [And] that would not benefit anyone.” The UK and Canada have announced that they will follow suit, the US has pledged $4 billion towards equitable vaccine distribution for poorer nations, and Spain has announced that it will be selling 30,000 of its surplus doses to Andorra. Meanwhile, the European Commission has left the manner of redistribution up to individual countries.

To aid this process, companies such as Pfizer, Sanofi, GSK and Curevac have struck deals with each other to produce larger quantities of vaccines. However, these deals have failed to address equitable distribution, as they continue to give preference for additional vaccines to the highest bidders, without making provisions for those waiting at the back of the line.

Against this backdrop, the UN Security Council (UNSC) recently passed a resolution that calls for the more equitable distribution of vaccines in conflict-hit or impoverished countries, where 160 million of the world’s population resides. The resolution calls for “the urgent need for solidarity, equity, and efficacy” in combating the pandemic in “countries with limited access to vaccines”. Crucially, it “invites donation of vaccine doses from developed economies and all those in a position to do so to low- and middle-income countries and other countries in need.” It also calls on member countries to “take measures to prevent hoarding in order to ensure access to inoculation, especially in conflict zones”. However, these resolutions are ultimately merely suggestions, and cannot in and of themselves push for more equitable vaccine distribution aside from perhaps raising awareness about the need to do so.

One way to ensure more equitable access is for governments to apply pressure on pharmaceutical companies to fulfil corporate social responsibility by waiving intellectual property rights or sharing their technology with the unvaccinated portion of the world, as AstraZeneca did. This must be accompanied by pushing for deals that allow vaccines to be manufactured locally in recipient countries, which would ultimately reduce the cost of production and ergo, price.

Since profit-driven companies have little need for international diplomacy, the government must take up this responsibility. To make this a reality, Amnesty International has been campaigning for vaccine-makers, including AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Moderna, to share resources. But so far, most companies barring AstraZeneca, have largely only sold to the highest bidders.

In order to effectively combat the scourges of vaccine nationalism and hoarding, the global community must come together to impress upon rich, Western nations the need for equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. The interconnectedness of today’s global economy makes financial self-preservation a compelling reason for HDC, alongside the strategic benefits of “vaccine diplomacy”. Whether or not this self-interest is combined with a moral obligation is ultimately irrelevant so long as MDCs and LDCs are able to meet the public health needs of their populations. However contrived, there is an urgent need for solidarity amongst the nations and pharmaceutical companies of the world to minimise the long-term impacts of a pandemic that has already driven several countries to the depths of desperation and destruction.

How Can the West be Pushed to Abandon Vaccine Hoarding?

The interconnected nature of today’s global economy means that aside from moral pressures, developed countries also have a self-interest in combatting vaccine inequity during the ongoing pandemic.

March 12, 2021

SOURCE: JESSICA RINALDI, REUTERS