The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) recorded its second consecutive victory in the 2020 Delhi Assembly Elections. Its welfare and subsidy policies have been richly awarded, garnering significant support from Delhi's women and youth in particular. AAP has provided free bus rides for women, free electricity for up to 200 units, free water for up to 20,000 litres a month, fee-waivers and free tutoring for students from low-income families, and free primary healthcare, amongst a host of other provisions. Opponents and several economists have termed these policies as ‘freebies’, denouncing them as populist and poor economic choices.

AAP has steadfastly defended its policies, saying that it has maintained a budget surplus and has not increased taxes. In fact, the state finances report by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) calculated that Delhi has the highest funds available in the country for development spending and could have spent Rs.20,142 crores in the financial year 2019-20 while remaining within the fiscal deficit limits. The fiscal deficit of the Delhi government was the lowest in the country in the previous financial year. Moreover, the Comptroller and Auditor General’s Report (CAG), 2019, states that the Delhi government has consistently run a revenue surplus. Thus, AAP argues that its policies are fiscally prudent and that its freebies are not disrupting the state’s finances.

Water and electricity subsidies were crucial in AAP maintaining its incumbency during the recently concluded assembly elections. Aside from providing up to 20,000 litres a month and electricity for up to 200 units for free, AAP also subsidizes electricity bills for up to 400 units by 50%. Water subsidies are not only fiscally prudent; they have also reduced wastefulness amongst consumers, with the Delhi Jal Board reporting that the Rs. 400 crores spent on water subsidies from 2017-18 resulted in water conservation as consumers reduced their consumption to avail the benefits. The subsidies have coincided with infrastructural improvements, with an increase in functional water meters from 8.57 lakhs in 2015 to 14.67 lakhs in 2018. Furthermore, AAP has considerably extended the water supply as 80% of the state's population now has access to direct tap water.

Nevertheless, critics say that although this may appear fiscally prudent in the short-term, it will become financially unsustainable in the long-term. According to Delhi's minister, Satyender Jain, water subsidy scheme coverage has reached 47 lakh consumers and the budgetary bill could amount to Rs. 2,250 crore per year.

Experts also suggest that subsidies on electricity usage could leave power companies in debt. Moreover, the scheme itself is regressive as the absolute subsidy increases with rising consumption. For instance, households consuming 0-100 units of electricity get a subsidy of about Rs.1,000 annually while those consuming 300-400 units get around Rs.9,000. Thus, the scheme appears to subsidize richer households to a greater degree as these households typically have higher electricity usage.

Another policy that has polarized views over its intent and impact was free rides to women on all state-run buses. The underlying assumption was that it would increase women's mobility and presence in public spaces and in turn ensure women’s safety. Kejriwal has also promised to extend the scheme to students.

An increase in the prices of the centrally-run metro led to 69% of users considering it unaffordable, with around 70% saying that they would be pushed towards choosing a less safe travel option for commuting. A 2005 study in Delhi slums reported that women spend more time traveling in slower modes of transportation as faster ones are more expensive, thus impacting their livelihoods. Women also avoid visiting healthcare centres unless absolutely necessary, which impacts their wellbeing. Therefore, there is a clear link between public transportation and women's mobility and empowerment.

Whether the cost of these subsidies is offset by the added economic benefits of increased female labour force participation is unclear; however, AAP government has raised minimum wages from Rs. 9,500 to Rs.14,000, and increased the salaries of Anganwadi and ASHA workers.

Although it has been criticized for its water and transportation policies, AAP has been lauded for its educational and health policies.

Under its watch, the quality of government schools has improved significantly. The government also provides financial assistance for educational coaching to students from Scheduled Castes (SC), Other Backward Classes (OBC), and economically weaker sections under its Jai Bhim Mukhyamantri Yojana. Students with a family income of less than Rs.2 lakhs receive 100% assistance, while students with a family income between Rs.2 to 6 lakhs receive 75% assistance. Apart from the free coaching, students are also provided with a monthly stipend of Rs.2,500. Around 5,900 students are estimated to have benefited from these schemes, with several gaining admission to higher educational institutes.

As part of its healthcare policy, AAP has made Mohalla Clinics one of its flagship programs. These primary health care clinics provide free treatment, medicines, and test facilities. The government also provides free surgeries in empanelled hospitals and bears the expenditure for the treatment of fire burn and road accident victims. According to a 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) report, 67.78% of total health expenditures in India are paid out of pocket, with the Union Health Ministry noting that medicines pose the greatest financial burden. In fact, one study claims that roughly 55 million Indians are pushed into poverty each year due to out of pocket expenditure on healthcare, with 38 million of them falling below the poverty line due to expenditures on medicines.

By increasing enrolment rates and reducing high dropout rates in schools, and making healthcare more affordable, AAP reduces the financial burden on those from weaker economic backgrounds. These schemes provide the possibility of upward social and economic mobility.

That being said, while AAP rightly claims that such schemes are not driven by increased taxes or fiscal imprudence, much of the surplus that it relies on was generated by Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal's predecessor, Shiela Dixit. Delhi had a revenue surplus of 4.2 GSDP in 2010-11, which is now coming down with each passing year. Even the own tax revenues (OTRs) have fallen from 5.49% of GSDP in 2015-16 to 4.93% in 2018-19. Hence, although Delhi continues to operate with a budget and revenue surplus, this is largely due to the existing surpluses created under the previous government. The fiscal prudence of AAP's policies are thus thrown into question when one considers that these surpluses are dwindling.

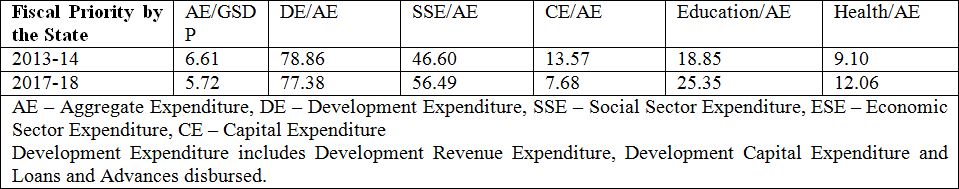

While expenditure on education and healthcare has increased, capital infrastructure–investment in new infrastructure–is falling. Thus, AAP's welfare schemes have come at the cost of asset creation and raising the state's productive capacity. In addition, expenditure on water supply and sanitation, urban development, roads, and bridges have also received lower allocations.

Although AAP's welfare policies have targeted power and water availability, it must also redirect some of its focus towards long-term systemic and structural issues of environmental pollution, transportation, women’s safety, water quality, and unemployment. Initiatives like the odd-even scheme are bandaid short-term fixes with temporary effects. There is also a lack of state-run buses; AAP's plan of rolling out 3000 buses and 1,000 electric buses by the end of 2018 remains unfulfilled. The cleaning of the Yamuna river and sewage and landfill treatment is also severely lacking. The unemployment rate rose from 3.1% in 2015-16 to 9.4% in 2017-18. Therefore, subsidies on water and electricity, coupled with increased state expenditure on health and education are crucial as they offer the possibility of upward social and economic mobility. However, many of AAP's policies have not been supported by infrastructural commitments, which impedes the long-term viability and success of its welfare schemes.