In the past few years, multilateralism has taken a beating, particularly in light of the Trump Administration’s inward-looking campaign and focus on making America great again. The high level of uncertainty prevailing in the current world order, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, has brought multilateralism or the need for it back into the limelight. The US’ preliminary response following the coronavirus pandemic has been to decouple from China, and other nation-states are following suit. This has precipitated an impending phase of heightened nationalism coupled with a legitimacy crisis for multilateral institutions such as the World Health Organisation. Given these developments, it is pertinent to understand and analyse where India’s engagement with multilateralism is headed.

India’s approach to multilateralism is characterised by the policy of non-alignment from the Cold-War era, and Prime Minister Modi has claimed that his foreign policy is a departure from this old tenet. Modi, in his speech at the Economic Times Global Business Summit in March 2020, stated that India remains neutral, but its neutrality is impinged on “friendliness” and not proximity to certain blocs as seen in the past. In fact, in the early days of the Cold War, India turned to multilateralism to magnify its influence on the international stage “until it could exert influence more materially”. Nehru’s support of multilateralism came from his belief in the United Nations (UN). However, two instances led to New Delhi’s faith in multilateralism to waiver. The first was the UN’s push for a plebiscite in Kashmir in 1948 and the second instance came in 1962 when Nehru could not garner enough international support against China during the border dispute. In fact, only three countries from 25 non-aligned nations responded to India’s call of declaring Beijing as an aggressor.

Alongside this historical baggage, India’s stance on the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty (NPT), climate change, and trade have garnered it an image of being a naysayer in multilateral negotiations. For instance, the blame for the breakdown of the Doha Round of trade negotiations in 2008 was placed on India and then Commerce Minister Kamal Nath. In regard to the proposed deal, Nath stated, “I reject everything,” and reiterated how India’s domestic interests outweigh the tabled offer. More recently, India’s withdrawal from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) last year further crystallized its image of preferring bilateral arrangements over multilateral mechanisms when it comes to trade. Modi government’s decision to pull out of RCEP was lauded domestically, in light of fears that the Indian market would be flooded by imports and crowd out local producers and products, particularly from China.

Accordingly, Indian scholar Karthik Nachiappan argues that India’s defensiveness in negotiating multilateral trade deals must be contextualised within its right to safeguard its interests, and not as a reflection of its antipathy to multilateralism. Traditionally, in the domain of International Relations, multilateralism is defined in terms of managing transnational problems by three or more parties by operating based on “mutually agreed generalised principles of conduct”. The definition implies that principles of multilateralism take precedence over the state’s interests, thereby, making it an organising principle of global governance. When viewed through this definition, India would appear to be unfavourable towards multilateralism. But, this is not the case, given that most countries seek to defend their national interests. Furthermore, with the rise of multipolarity in the international system, there is a reluctance to accept binding multilateral arrangements by nation-states, wherein President Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris Agreement in 2017 serves as a reflection of how power politics precedes multilateral cooperation. Similarly, with reference to the collapse of the Doha round of negotiations—several countries, including the US, China and even the EU—refused to make concessions on their interests, yet the breakdown of the talks was unfairly attributed to India and Nath.

In truth, India’s trade approach marries a healthy mix of pursuing regional and multilateral arrangements, as evidenced by India’s simultaneous active participation at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and signing of regional trade agreements. For instance, when New Delhi could not obtain the desired outcome at the 2008 Doha Round, it fell back on regional trade arrangements to further its economic growth. New Delhi’s free trade agreements, with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the signing of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) indicating a firm commitment to regional frameworks. Hence, a significant characteristic of India’s trade policy is following a multi-track approach that favours both regionalism and multilateralism. Despite prevailing domestic concerns, India went ahead and ratified the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) at the WTO in 2016, showcasing its engagement with multilateral mechanisms. The agreement aims to expedite the movement, transit, and release of goods, and, its objectives, according to Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, were deemed to be in “consonance with India’s ‘Ease of Doing Business’ initiative”. Therefore, despite some suggestions otherwise, India is indeed engaging at both the regional and multilateral level to further its trade policies.

Furthermore, away from the traditional definition of multilateralism, Risto Penttilä argues that creation of informal forums such as the G-8 (now G-7, following removal of Russia in 2014) and G-20 represent a shift towards a “lighter multilateral system”. India’s participation in the G-7 summit last year was regarded as an acknowledgement to its growing economy and active inclusion in informal multilateral forums.

However, fast forward to 2020, a lot has changed, and multilateralism is facing a new crisis amid the ongoing pandemic, wherein the US is advocating a policy of decoupling from China and other states such as South Korea and Japan are following suit. India, too, is advocating a policy of decoupling, owing to its stand-off with China along its border with the East Asian giant. Amid these tensions, it appears as though India could benefit from countries decoupling from China. The prevailing anti-China sentiment, especially in the wake of the coronavirus epidemic, has placed New Delhi in a unique position to expand its trade footprint. According to a report by Singapore’s DBS Bank, India can gain “particularly under categories on which the US has imposed tariffs on China”. In line with this trend, South Korea is looking at India as an alternative to diversify its supply chains away from China. India’s ban of Chinese apps and increasing trade barriers on goods to prevent the re-routing of Chinese goods into India from other Asian countries reiterate its mistrust of China and advocacy for a policy of decoupling. Indicating India’s corporate sector’s tryst with multilateral arrangements, Sunil Mittal, Chairman on Bharti Enterprises said, “India has always been open to multilateral agreements, but things have not gone the way we would have hoped.” Therefore, it can be argued that amid growing mistrust of China, multilateralism is undergoing a makeover, wherein the fractures in international relations are widening to form more distinct and separate trade and diplomatic blocs.

Nevertheless, Former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran has argued that multilateralism can be reinvigorated. He makes a case that, at present, the international system is confronting cross-domain challenges such as global economic loss, challenges to health security erupting from the epidemic which necessitates multilateral solutions. Echoing these sentiments, Amitabh Mattoo and Amrita Narlikar opine that India can simultaneously pursue both multilateralism and decoupling, wherein India can “build a coalition to bridge” the trust deficit caused by China through regimes that both incentivise and sanction Beijing to adhere to international norms.

Developing a multilateralism within Indian characteristics appears to be the way forward, and Indian scholars view the concept of multilateralism as more regional than universal and more normative than institutional. This understanding is reflected in India’s trade policy, which involves a multi-track approach of simultaneously pursuing bilateral, regional, and multilateral engagements. Essentially, India’s approach to multilateralism, when analysed from the domain of trade, is tethered to both formal and informal norms, combined with a thrust for regionalism. However, India places informal rules, such as a focus on consensus building, above formal institutional mechanisms practised in the WTO, and its conceptualization of multilateralism is rooted in regional collaboration, as witnessed in its Look/Act East policy. The ongoing strategic decoupling by the US appears to be a unilateral response to China’s revisionism of the world system, and India’s understanding of multilateralism could act as a salve to the decline of the concept. The unpopularity of the multilateralism notwithstanding, India should partake in strengthening multilateralism in general, particularly in the domain of trade. Accordingly, in the wake of rising anti-China sentiments, India should maximise its position of representing the developing countries and work with the developed world to shape multilateralism in the changing world order using multilateral forums such as the WTO.

Discerning India’s Approach to Multilateralism in a Time of Unilateralism

While decoupling with China, India should seek to reinvigorate multilateralism using trade

August 19, 2020

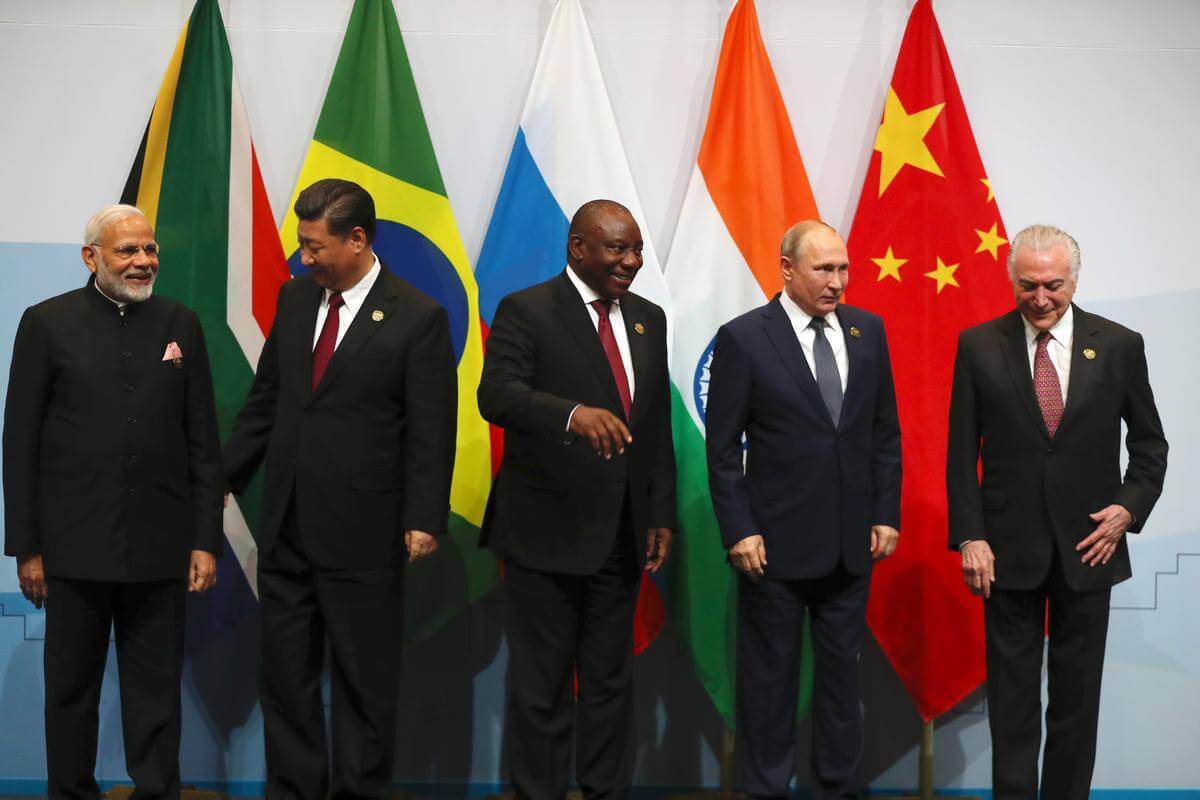

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi with heads of China, South Africa, Russia and Brazil at the BRICS summit meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa, July 26, 2018. SOURCE: REUTERS/MIKE HUTCHINGS