Military reverses of the Soviet Union and the United States in Afghanistan over recent decades mirror the experiences of Colonial Britain in the 19th century. These episodes have solidified the South Asian nation’s reputation as the ‘graveyard of superpowers’. As the US military moves forward with its full withdrawal from the country in accordance with a peace accord recently concluded with the Taliban, Afghanistan stands to assume renewed prominence in the Chinese Communist Party’s geopolitical calculus. In this respect, the evolution of Chinese strategy in Afghanistan since 2001 will have a direct bearing on the manner in which the regional security environment is likely to shape up, and how this will in turn impact the interests of other stakeholders across Central and South Asia.

From the moment when the first Soviet tanks rolled into Afghanistan on Christmas Day, 1979, the nation has been engulfed in a near-constant state of war. To date, there have been three distinct phases of the Afghan conflict: 1) the Soviet invasion and western-backed Islamic insurgency (1979-1989), 2) the Afghan Civil War (1989-1992) and the rise of the Taliban (1994-2001), and 3) the American invasion and ongoing Taliban insurgency (2001-present). Over the course of the past four decades, Afghanistan has become a focal point of geopolitical contestation. Following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and its collapse two years later, a diverse group of global power have cultivated a growing set of interests in the embattled country. Iran, India, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, and the Central Asian republics all view the future of Afghanistan as a matter of strategic import.

Presently, Afghanistan stands at the threshold of an uncertain next chapter in what has been a troubled modern history. In response to the 9/11 terror attacks that emanated from the Taliban’s then-Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the US launched a full-scale invasion. Its initial mission of uprooting transnational terror organizations like the al-Qaeda under the protection of the Taliban gradually morphed into a broad and poorly defined military occupation cum nation-building project. Condemning itself to repeat history through muddled policy and the absence of a long-term strategy, the performance of the US military in the rugged country has yielded much bloodshed and little in terms of constructive results. After years of stalled negotiations, in February 2020, the US and the Taliban concluded a comprehensive peace agreement. While a fuller treatment of this deal’s contents is beyond the scope of the present discussion, suffice it to say that it is unlikely to deliver either peace or a stable future to Afghanistan. As the US continues to draw its in-country forces down to zero, China is eyeing the contested nation with newfound anxiety.

The pullout of the remaining US forces from Afghanistan coincides with China assuming an increasingly confrontational and assertive role in the regional sphere. A number of noteworthy departures from precedent have been observed in the past decade under the tenure of Chinese President Xi Jinping who, as of 2018, is qualified to remain in office for life. In contrast to its previous maxim of “hide your strength and bide your time”, the change in tone under Xi has been characterized by a more proactive and aggressive approach to securing China’s vital interests both at home and abroad. Escalating tensions in the South China Sea, Sino-Indian clashes on their disputed Himalayan frontier, and China’s expanding global footprint as a consequence of the Belt and Road Initiative all testify to this shift in Chinese foreign and military policy.

The Chinese-Afghan frontier is the smallest land border China shares with any of its fourteen neighboring countries. In part thanks to the vagaries of geography, Afghanistan was of marginal strategic interest to China prior to 9/11. However, since the early 2000s, Beijing has become increasingly fixated on the potential terrorist threat emanating from beyond its porous inner-Asian frontier. One militant group, in particular, has risen to prominence—in the eyes of the Chinese security establishment, at least—as the Uighur terror-threat incarnate. The origins of the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) are obscure, but, in the past fifteen years, a growing body of evidence has emerged on what is currently the premier Uighur terrorist outfit. The group’s leader, Abdul al-Haqq al-Turkistani, has occupied a seat on al-Qaeda’s executive shura council since 2005, and it enjoys cordial ties with the Taliban leadership. Through the 2010s, the TIP has effectively maintained a military presence in Afghanistan. For instance, as recently as December 2019 the TIP released new footage of its training camps and heavily-armed fighters in the Badakhshan Province (which borders Chinese Xinjiang). Since 2015, the group has also deployed a contingent of Uighur fighters to join the ranks of the Salafi-jihadi resistance battling the Assad regime in the Syrian Civil War.

When considered alongside the intensifying threat posed to its national security by the TIP and kindred groups, Chinese policymakers are undoubtedly eyeing US withdrawal from the region with great interest. In fact, Beijing has begun to pursue a strategy of containment vis-a-vis Afghanistan that further evidences China’s growing assertiveness on the international stage. This push to “secure the perimeter” has been characterized by a number of hard-power projections that directly impinge on Indian and future American interests in the region.

Recently, China has been quietly expanding its footprint in neighboring countries along its porous Central and South Asian periphery. In late 2016, allegations surfaced that the PLA was conducting joint patrols with the Afghan military in the remote Wakhan corridor. While Beijing adamantly denied the presence of Chinese troops on Afghan territory, a government spokesperson did acknowledge the conduct of joint law-enforcement exercises in the area. While the details remain murky, the departure of the remaining US forces from the theater is likely to catalyze a more overt PLA presence on the ground in Afghanistan.

China has also begun securing the flanks of the Wakhan Corridor by developing military infrastructure in neighboring Tajikistan. Since at least 2017, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has maintained a base in Tajikistan overlooking the Afghan-Chinese border that, according to satellite imagery, is equipped with heliports and has the capacity to hold a battalion-sized contingent of light infantry. Tajikistan, whose long and porous land border with Afghanistan have endowed it with an intractable jihadi challenge of its own, has traditionally fallen under the Russian security umbrella. In light of Xi and Putin’s deepening bilateral ties, China’s creeping military presence in Tajikistan apparently comes with Russia’s blessing and may signal an expanding Chinese military presence in the region as a whole.

The third external variable at work in China’s Afghan equation is Pakistan. China and Pakistan have enjoyed particularly cordial ties for decades, united by their joint opposition to the prospect of Indian regional hegemony in South Asia. In terms of soft power, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which includes Xinjiang and the entirety of Pakistan, is considered the ambitious initiative’s centerpiece. However, the CPEC crosses through the disputed territory of Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK), deepening the geopolitical game of chess currently being conducted between the PRC, Pakistan, and India in this contentious neighborhood.

Like Afghanistan, Pakistan has also served as a refuge for its fair share of terrorist groups since the Western-backed jihad against the Soviet Union of the 1980s. The top leadership brass of al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and the TIP have used Pakistan as a safe harbor for decades. China is well aware of this fact, and has taken meaningful steps to improve security for CPEC infrastructure and Chinese assets in Pakistan. To date, both nations vehemently deny the presence of PLA forces in Pakistan. However, in late 2015, the Pakistani military announced its formation of the Special Security Division (SSD), whose explicit mandate is to ensure the security of the CPEC. Composed of over 17,000 troops operating under the command of a brigadier general, the SSD demonstrates the degree to which Chinese interests are shaping Pakistan’s military force structure and domestic security agenda.

In sum, China’s geopolitical strategy in Afghanistan is currently in transition. Historically, the grandiose ambitions of superpowers in Afghanistan have been violently checked. The most recent iteration of this pattern, the American invasion of 2001, has prompted a rising China to reconsider its strategic approach to Afghanistan in the face of an emerging power vacuum. Deeply concerned by the nexus between domestic unrest and the transnational terror threat posed by groups like the TIP, securing its political and military interests in Afghanistan have become a strategic priority for China. To this end, Beijing policy of containment manifests in a bolstered military presence in the Wakhan Corridor quadruple-point between China, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. In an aggressive break from precedent, these Chinese hard-power deployments along its Central and South Asian periphery foretell an impending collision with Indian and American interests in the region. As India contemplates the looming reality of a post-American Afghanistan, it would behoove policymakers in Delhi to better understand the evolution of China’s interests and emerging strategy towards Afghanistan.

China and the Future of a Post-American Afghanistan

As China occupies the strategic vacuum US withdrawal from Afghanistan portends to create, Indian interests are likely to be compromised.

September 1, 2020

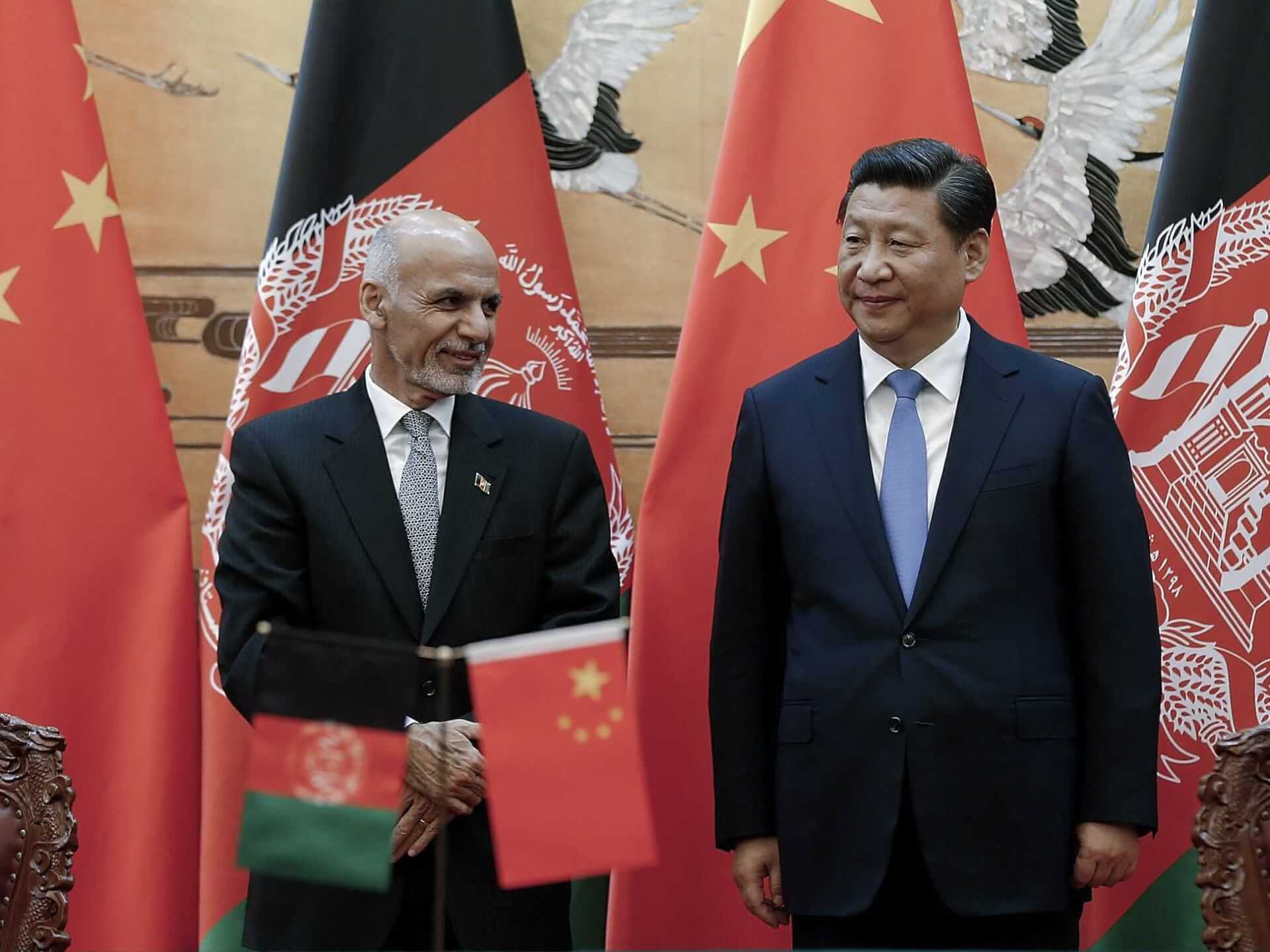

Afghanistan President Ashraf Ghani (L) with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping (R) SOURCE: