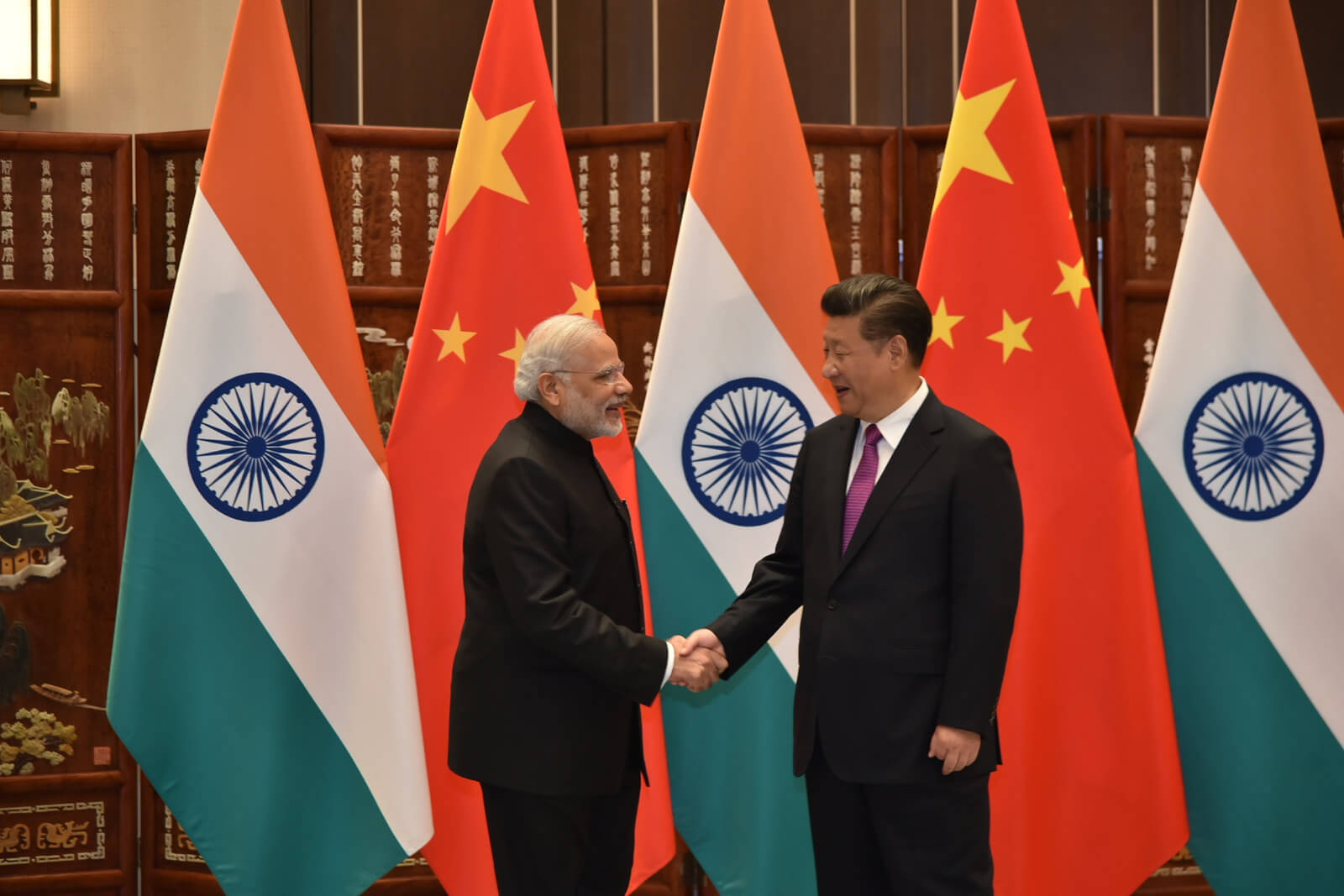

The death of twenty Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese soldiers on June 15 in Galwan valley region instigated a series of events that worsened the already scarred Indo-China relations. Despite both sides claiming to have agreed to de-escalate in the area, any success in bilateral diplomatic negotiations appears distant as both countries continue to increase their military presence and infrastructure in the region. However, it is beneficial for both parties to avoid engaging in a full-blown military altercation, as it will prove to be devastating to the economy and security interests of both the countries.

Also Read: India Blocks 59 Chinese Apps Over “Sovereignty and Integrity” Concerns

In the absence of reconciliatory bilateral discussions, questions have arisen as to whether this dispute should be resolved by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the judicial arm of the United Nations. While India has previously indicated its reluctance to take any border-related issues to the ICJ, calling for the international body to resolve the dispute could prove beneficial, as it could pave the way towards a solution, rather than leaving the matter unsettled. Primarily, the financial costs for India are incredibly high. India retaliated with economic actions, such as toughening up quality control measures, pushing out Chinese firms from domestic projects and urging local consumers to boycott Chinese products. While it has vowed to reduce Chinese influence in Indian markets, it will be a problematic short-term goal to achieve. In fact, India’s largest trade deficit is with China. In the fiscal year of 2018-2019, China exported goods worth $70.3 billion to India. On the other hand, Indian exports to China were worth merely $16.7 billion.

It must be noted that the limited jurisdiction of the court creates several hindrances to the Galwan dispute being resolved in the ICJ. During the discourse that established the ICJ, several states expressed concern about a prospective threat to their sovereignty due to an all-powerful judicial body. Hence, the ICJ statute limits the powers of the court from ruling on the rights of a country by making it contingent on the states accepting the jurisdiction of the body. While India does recognise the jurisdiction of the court, in its declaration, it clarified that the power of the ICJ to resolve international disputes would not apply to cases which concern or relate to “the status of its territory or the mediation or delimitation of its frontiers or any other matters concerning boundaries”.

On the other hand, China doesn’t recognise the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ. In fact, China has previously been resistant to accepting the authority of international bodies, specifically for issues relating to territorial disputes. The best example for this is the South China Sea (SCS) decision by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, which dealt with the dispute between the Philippines and China. In this case, the tribunal passed its ruling on several issues in the disputed region in the South China Sea, including the validity of the nine-dash line, which is the demarcation China uses to claim its “historical rights” against the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam. The UNCLOS ruled in favour of the Philippines. However, the Chinese foreign ministry rubbished the judgement as “null and void” saying that China “neither accepted nor recognised” the award. In fact, China continued to flout the decision by using its military power to intimidate the Philippines. In 2017, Philippines’ President, Rodrigo Duterte, said that Chinese President Xi Jinping was threatening to declare war if the Philippines decided to utilise the gas reserves of the region. Hence, hypothetically, even if the Galwan case is consensually brought to ICJ, a non-favourable verdict is likely to be disregarded by China.

Another way a dispute can be brought before the ICJ is through the United Nation Security Council (UNSC) exercising its power to call upon countries to settle a dispute before the body. However, China is a permanent member of the UNSC, and will definitely block the referral of the Galwan dispute, as accepting any such claims would result in all of its territorial disputes, specifically those in Southeast Asia, being brought into question.

Since the traditional route of filing a case before the ICJ is not viable in the current situation, India could appeal to other organs of the UN to seek a non-binding advisory opinion on the issue. This strategy was adopted by member states, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Kuwait, who, through a General Assembly resolution, sought an advisory opinion of the ICJ on the legality of the construction of the wall by Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. As can be seen in the Israeli wall case, while these opinions are not binding, they are looked at as “authoritative assessments” of such issues and are influential in swaying the opinion of the international community. As a result, any further activity by the defaulting country will consequently be considered as “unnecessaryprovocation”. Moreover, it could persuade countries to impose other forms of diplomatic pressures, like economic sanctions, on countries defying such opinions of the ICJ.

India also appears to have a stronger historical claim to the region, which the ICJ is likely to support. There are two aspects that the court typically looks into while assessing a country’s claim to the territory – the first possession of the disputed property, and the length of unfettered control. As for “historical priority”, several security experts of the region call China’s claim over the Galwan region unprecedented. Former Northern Army Commander Lt. Gen. DS Hooda says that the area was “never a dispute in their own maps and their own historical accounts” and is merely an attempt by the Chinese to “gain some strategic advantage”. Further, in 1990, the region was not included in the list of the 12 disputed areas in Ladakh that two sides sketched out. Even the claim of duration lies in favour of India. Following the intrusion in 1962, when Chinese forces trespassed into Indian territory and eventually withdrew from the region, India has held peaceful and undisturbed control over the area.

India’s relatively favourable position in the international community will also benefit its standing in a multilateral body like the ICJ. While partisanship in the ICJ as an institution is difficult to establish, several studies show that individual judges support positions that adhere to their personal biases. For instance, 90% of the times, judges vote in favour of their home country. Moreover, judges are also likely to vote according to the political stand of their country of origin, by voting in favour of their strategic partners. Further, members of the court have also proven to be swayed by the publicopinion of the international community. While India continues to expand its influence as a global player, China’s reputation has been severely impacted because of the COVID-19 pandemic, with several countries blaming the lack of transparency of the Chinese government for the extent of the global devastation caused by the outbreak. Moreover, China is also facing flak from other countries like the US, Japan and Australia over its “maritime ambitions.” In fact, the aforementioned countries are collaborating with India to check China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

Also Read: US House Foreign Affairs Committee Holds Hearing Titled “China’s Maritime Ambitions”

While other border issues, such as the ongoing one in the Kashmir Valley, may not be as favourable for India to resolve through the ICJ, the resolution of the dispute with China on the Galwan region skirmishes by an international body is definitely one that would benefit its claim to the territory. With India itching to secure its position as a permanent member of the UNSC and establish itself as an international power, relying on organs of the UN for dispute resolution will also show its determination towards maintaining the sanctity of such multilateral bodies. Further, this could also strengthen the credibility of its title amidst international actors. However, this may manifest into an opening for other countries, such as Pakistan and Nepal, to bring their territorial claims against India before the ICJ. With its persisting scepticism to surrender its jurisdiction on its border disputes to any third party, will this be a can of worms India is willing to risk breaking open?

India-China Border Dispute Coverage:

- India-China Skirmishes in Sikkim and Ladakh Leave Several Soldiers Injured

- Indian Army Chief Addresses Simmering Tensions with Nepal, China, and Pakistan

- Multiple Chinese Army Incursions Reported Along LAC, Indian Army Chief Takes Stock

- PM Modi Meets With Top Military Brass to Discuss Escalating Indo-China Border Tensions

- Donald Trump Offers to “Mediate” India-China Border Dispute

- PLA Keeps Up Pressure on LAC Amid Border Tensions with India

- India, China Increase Military Presence Along LAC

- India, China Agree to Gradual and Verifiable Disengagement in Eastern Ladakh

- India and China Pull Back Troops From Three Key Areas in Eastern Ladakh

- India-China Tensions Continue as Satellite Images Show Resurgence of Chinese Posts

- India Imposes Economic Sanctions on China Following the Death of 20 Indian Soldiers

Image Source: The Diplomat