The last few weeks have seen shocking and heart-wrenching images coming out of Ecuador–of bodies abandoned on sidewalks and wheelchairs, packed in cardboard coffins, and stacked in mass graves–as the coronavirus exacts a horrific toll on the country’s impoverished residents and overwhelmed authorities. The Andean nation is suffering one of the worst outbreaks in the world, and is painting a cruel picture of the debilitating effects of the virus on not just healthcare care systems and the economies in developing countries, but also on their governments’ ability to keep track of its spread.

Ecuador’s Guayas province has emerged as the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in Latin America, with its capital, the port city of Guayaquil, estimated to have incurred over 8,000 deaths. According to official data, the number of deaths in Guayas jumped from a normal average of 3,000 to nearly 11,000 in the six weeks between the beginning of March and mid-April. However, the true scale of the crisis has largely been obscured by the government’s inability to determine who has the virus and to engage in contact tracing, which is exacerbated by the global shortage of testing kits and personal protective equipment (PPE).

Infectious diseases are not a new phenomenon for the country. Despite covering only 110,000 square miles, the nation has borne the brunt of a tremendous diversity of such diseases. The spread of COVID-19 is currently coinciding with one of the largest dengue epidemics in the broader region, with a total of over 3 million cases. Of those, 8416 cases are in Ecuador, with 84% of the cases in Guayaquil. This could explain the disproportionate vulnerability of Ecuadorians and the tremendous devastation brought about by the coronavirus in the country, despite having a relatively young and rural population.

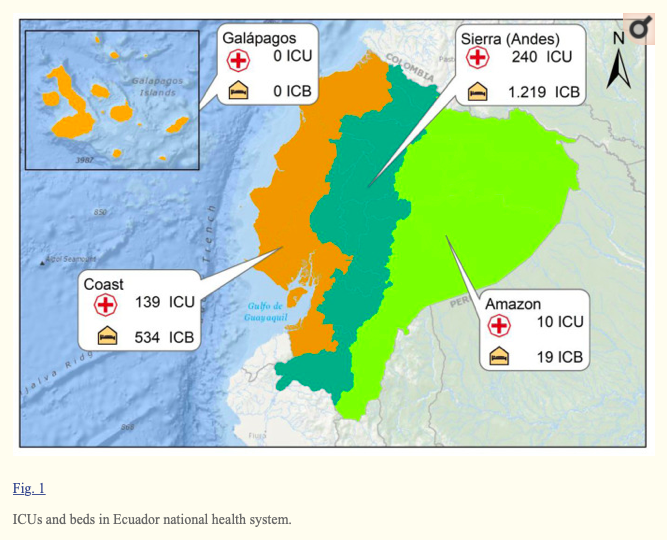

Ecuador has four geographic regions with marked climatic, social, and traveler’s entry differences–Coast, Andeans-Sierra, Amazon, and the Galapagos Islands. The most significant public health problems occur on the coast, with Guayaquil serving as the primary source of transmission and contagion as it is the country’s main commercial hub. The first reported case of COVID-19 in the country was a woman who flew into Guayaquil from Madrid in mid-February. Spain, which is one of the world’s coronavirus hotspots, is also home to approximately 400,000 Ecuadorian migrant workers and expats, many of whom rushed home to Guayas due to the pandemic. Today, almost 80% of the total COVID-19 cases in the country are concentrated in Guayas.

However, the government did not seem to understand the severity of the threat of the virus when it emerged. Just three weeks after the first case had been diagnosed, the governor of Guayas allowed the Libertadores Cup soccer game in Guayaquil to continue as scheduled; it was attended by over 17,000 fans. There is no data detailing the impact of this game on Ecuador’s COVID-19 case count. However, there were several instances of people attending public gatherings between March 4 and 18, even once local authorities had issued stay-at-home orders, illustrating the government’s inability to effectively contain the virus.

When President Lenín Moreno’s administration finally declared a state of emergency, initiating a national curfew and compulsory social isolation, it was clear that the government failed to consider its impact on the most vulnerable. The 2010 census showed that 26% of people in Guayaquil did not have access to drinking water, and 53% lacked a public sewage system. More than 60% of the population in Guayas have no records with the public social services network, indicating high numbers of underemployment, and 20% are cleaners, street vendors or laborers. Guayaquil is also the city with the highest poverty rate in the country, which stands at 11.2%. Since so many people live hand-to-mouth, without any government benefits and protections, adhering to government rules can mean starving. Thus, despite increasingly strict lockdown and curfew orders, Guayas residents are leaving their homes more than anyone in Ecuador.

The terrifying images of corpses on the streets, and devastation across the country resembling a war-zone prompted some government action. Though initially in denial about the severity of the horrors posed by the pandemic, Vice President Otto Sonnenholzner, who lead Ecuador’s response to the pandemic, issued a formal apology on April 4. “We have seen the images that should never have happened,” he said in a nationally televised address. He added, “As your public servant, I apologize.” Soldiers and police in Guayaquil have cordoned off many poorer virus-hit neighborhoods, enforcing strict lockdowns. In addition, a municipal task force made up of medics, firefighters, and city workers has gone house to house looking for potential cases, while sanitary workers have disinfected and fumigated public areas. Authorities have also created a corpse-collecting task force to clean up the streets, however, with morgues and crematoriums completely overwhelmed, bodies are being stored in industrial refrigerators. President Moreno has also announced the building of emergency cemeteries in the city, aimed at burying roughly 100 people per day.

Though officials are now stating that they are regaining control of the situation, the persistence of grave structural problems is magnifying the challenge of fighting the pandemic. Ecuador, with 17 million inhabitants, has just 389 intensive care units (ICU) (2 units/100,000 inhabitants) and 1183 ICU beds (7 beds/100,000 inhabitants).

Recently, the World Bank pledged $20 million to the country to finance the procurement of medical supplies needed to treat COVID-19 cases and the equipping of a larger number of intensive care and isolation units. Additionally, the funds are supposed to contribute to financing the national communication strategy and the dissemination of prevention and protection messages for the short and medium-term. However, given that the most vulnerable are disconnected from public systems, the task at hand will be challenging.

Ecuador’s vulnerability is compounded by the fact that the Moreno government has slashed funding to public health systems, with public investment in healthcare falling from $306 million in 2017 to $130 million in 2019. In 2019 alone, more than 3,000 health officials were laid off from the Ecuadorian Health Ministry, amounting to 4.5% of total employment in the ministry. Additionally, with extremely limited testing kits available, it is possible that only symptomatic patients are being tested for the virus, meaning that a majority of the cases are going undetected. In fact, Guayaquil mayor, Ms. Cynthia Viteri said, “We will never know what the real number is, because there are no tests.”

President Moreno’s declining popularity during one of Ecuador’s toughest moments in its 200-year history is also increasing tensions. Over the last two years, the Moreno government has used authoritarian tactics in order to persecute its opponents. By usurping the power of the judiciary, the administration has sought to crush opposition, by either imprisoning leaders, or forcing them into exile. Even in the midst of the current crisis, Moreno’s government is still waging an offensive against former President Rafael Correa to ensure that he cannot stand for office again. Furthermore, the government is already at odds with indigenous organizations - due to its 2019 decision to end fuel subsidies - and has faced criticism due to its enactment of the IMF-sponsored reforms. With elections due to be held in February 2021, Moreno continues to try to cling on to power, at the cost of social and economic stability and human rights as the country is tackling its immense and surging debt alongside an ever-increasing death toll. His governance has thus has left Ecuador gravely ill-prepared to deal with a pandemic, with critics arguing that he seems less focused on containing the virus than he is on advancing his own political ambition.

Furthermore, the economic cost of the pandemic has been compounded by the collapse of export revenues, ruptures in the country’s main oil pipelines, and massive foreign debt payments. Amidst falling oil prices, public debt has risen to nearly 52% of GDP, well over the stipulated limit of 40%. The country’s dollarized economy has also proven to be a double-edged sword, in that, while it has stabilized the economy and shielded citizens from inflation and economic shocks resulting from political turmoil in the region, the stronger dollar has also made Ecuador’s exports less competitive. In times of crisis like this, the government also cannot print dollars to increase liquidity in the country. Experts suggest that Ecuador’s gross financing needs this year could hit an “unmanageable” $8.1 billion this year, and that the economy is likely to contract by 6%.

The absence of money is also affecting the government’s ability to provide any immediate relief to those most affected by the crisis. Though an emergency fund could help provide some relief to the citizens of Ecuador, since the government will have to decide the parameters to decide who is “most vulnerable”, a large proportion of potential beneficiaries are bound to be left out due to current fiscal constraints.

Therefore, the government’s delayed response, defunding of critical medical infrastructure, and continued politicking amidst the ongoing pandemic has left Ecuador highly vulnerable and unable to tackle its twin crises of a crippling debt and a rapidly rising death toll. The larger, unfortunate reality is that Ecuador’s devastation may not be unique. As the pandemic has toppled some of the strongest economies in the world, it threatens to wreak even more destruction in poorer nations, which have weaker public systems, overcrowded homes, little access to basic utilities, and staggering levels of inequality. Any government measures must be in accordance with this reality in order to save the greatest number of lives and reduce the burden on the economy and healthcare system.

Image Source: openDemocracy