On March 23, Myanmar reported its first COVID-19 case, and, almost immediately, China stepped into action, sending two consignments of medical supplies, masks, thousands of testing kits, and personal protective equipment (PPE). In April, Beijing sent a 12-member medical team specialising in epidemics, infection control, and laboratory testing. It also sent medical supplies and laboratory equipment worth more than 4 million yuan to assist the ailing Southeast Asian nation. Apart from governmental aid, Chinese foundations, such as the Jack Ma Foundation and the Alibaba Foundation, have also donated medical supplies to Myanmar. Likewise, the State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC) donated mobile toilets and 1 million yuan worth of medical supplies to Myanmar. SPIC’s assistance is particularly significant, given that it is a significant stakeholder in Myanmar’s controversial hydropower projects, including the suspended Myitsone dam project in Kachin. However, Myanmar has been seeking to overcome its reliance on China and remains hesitant regarding Beijing’s motives for providing aid.

By no means is Myanmar the only state obtaining assistance from Beijing. In fact, by mid-April, the Chinese government had already provided aid to over 140 countries and even sent 14 teams of medical experts to 12 countries. This magnanimous assistance has led to suspicions and suggestions that China’s Covid-19 diplomacy is less about humanitarian assistance and more about soft power projection. Dubbed as “mask diplomacy” by Western analysts, the move is perceived as an attempt to shift the narrative from China being the cause for the outbreak of the virus to one who has successfully contained its spread. For instance, China sent thousands of masks, PPEs, and test kits to Egypt, and, in March, the economic giant put out a report detailing its COVID-19 assistance rendered in the Middle East. It was seen as a response to growing negative sentiments in the region against China for not controlling the spread of the virus at its onset. Consequently, China’s motivations behind delivering medical aid has been interpreted as a move to change this narrative. Apart from the Middle East, China also ramped up its COVID-diplomacy across South Asia, with several reports detailing its assistance to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. Interestingly, Nepal declined competing offers of medical aid from both China and India.

How then does the pandemic related aid from China to Myanmar differ from its aid to other countries? And, why is this important for India? Firstly, assistance to Myanmar stands out as it, along with Pakistan and Laos, was the only country that allowed military medical teams from China to contain the spread of the virus within its borders. This is revealing because it depicts a degree of trust at the bilateral level. Military medical teams rank higher than their civilian counterparts and hence indicate the importance Beijing attaches to Naypyidaw. Furthermore, the militaries of the two countries often conduct joint training exercises and technical exchanges, showcasing a high level of trust. Secondly, from the total Chinese aid given to all Southeast Asian states, Myanmar (and Laos) received a more significant share than other countries in the region. Apart from assistance from the central Chinese government, provinces within China have also disbursed aid to Naypyidaw. Myanmar was also one of the first to receive support from China, but this could be due to the close geographical proximity the two states share.

The underlying motivation for China’s COVID-diplomacy in Myanmar appears to be strategic and economic in nature, which is depicted through the pressure China put on Myanmar to hasten approvals of stalled economic projects soon after the aid was sent. Another motive for China may be its desire to change the global narrative, which has largely been critical of China. By engaging in COVID-diplomacy, China aims to ease the blame being placed on it for initially repressing information on the spread of the virus. However, in the case of Myanmar, this aid comes with certain strings attached. Media reports emerged that, in May, during a phone call, President Xi Jinping urged Myanmar to accelerate the implementation of the projects that were discussed during his visit to the country in January. Calling for the expansion of “practical cooperation”, President Xi maintained that implementation of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was necessary to further strategic interests between the two states. Alongside the government, Chinese companies have also used aid as a bargaining tool to pressurize Myanmar into implementing the goals of CMEC. For instance, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), which is the first Chinese commercial bank operating in Myanmar and which facilitates financial cooperation for CMEC projects, donated about 150,000 masks and 4,000 test kits to Myanmar’s Health and Sports Ministry. Similarly, government authorities from Baoshan city in Yunnan province sent aid worth 400,000 yuan to Myanmar’s Kachin State government. Like in the case of the ICBC, this aid is particularly telling, as companies from Baoshan have signed agreements with Kachin state to develop the Myitkyina Economic Development Zone (MEDZ) part of the strategic economic corridor.

Additionally, unlike the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), even before the pandemic, Myanmar was relatively slow in implementing CMEC projects. As a result, it has been suggested that Beijing’s COVID-diplomacy in Myanmar is underpinned by the need to expedite the progress of its BRI projects in the country. This is a point that has been reiterated by U Maw Htun Aung of the Natural Resource Governance Institute, who said: “China seems to be hoping that relations with Myanmar will improve and that there will be no more obstacles to their investments due to the help they are providing now.” These developments have given rise to growing concerns against Chinese investments in the country, as seen in the case of Myitsone Dam in the past.

More recently, security challenges arising from armed conflict between ethnic rebel groups and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) caused doubts over the future of the Muse-Mandalay Railroad project, which is part of CMEC. The rise in ethnic armed conflict has disincentivized other countries from investing in Myanmar, thereby increasing Naypyidaw’s dependence on Beijing and furthering the cycle of exploitation and manipulation that has been laid bare during the ongoing pandemic. Regarding the railroad project, U Ye Tun, a former member of Parliament from Myanmar, stated, “If companies from other countries do not compete in the tender due to security issues, China will have more opportunities to win the tender. It will be a one-sided competition, and it may lead to over-pricing or quality issues.” Therefore, Myanmar’s apprehension regarding China’s strategic investments is specifically with the fear of an impending debt-trap with its powerful neighbour. Myanmar is said to have an international debt of $10 billion, of which 40% is owed to China, propelling Myanmar to actively seek other partners, wherein India becomes a prominent option.

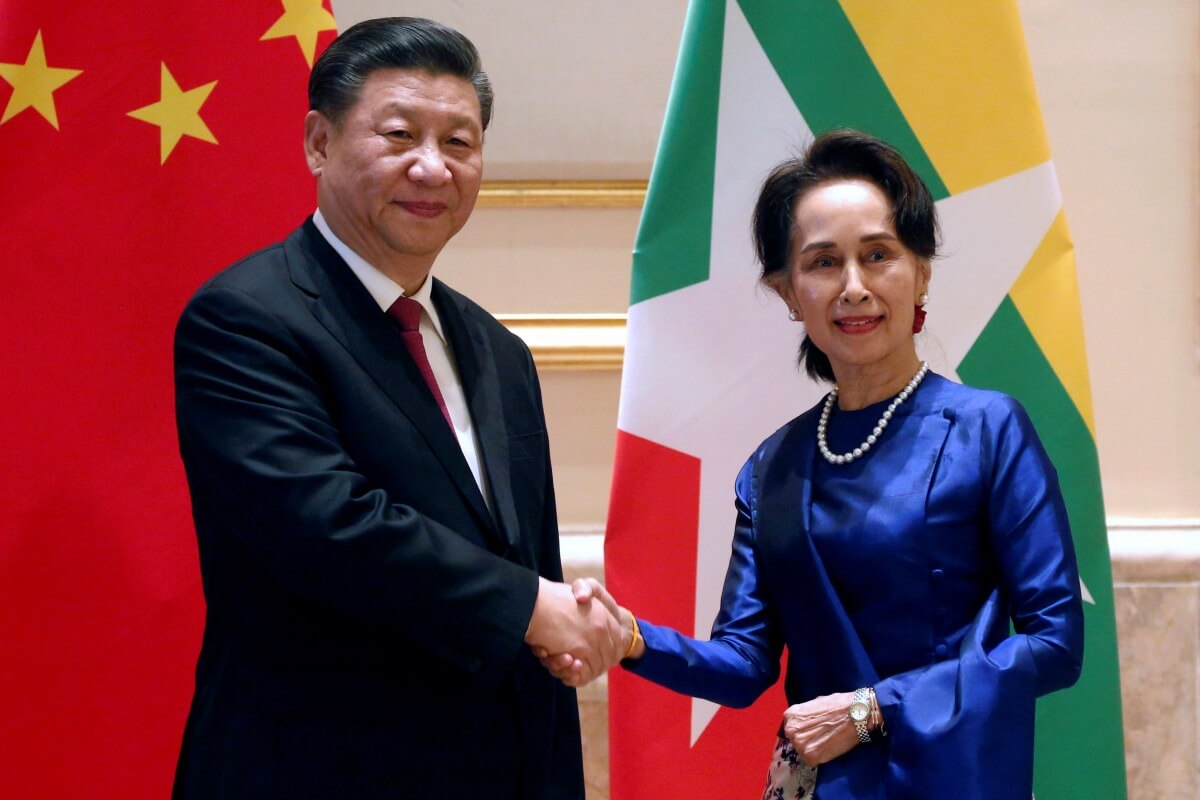

Like China, India, too, has provided aid to Myanmar during the pandemic. In a phone call with Myanmar's State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, Prime Minister Modi assured Naypyidaw that New Delhi is willing to provide economic and medical assistance to combat the spread of the novel Coronavirus. The initiative was part of India’s ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and came against the backdrop of China’s growing COVID-diplomacy in India’s neighbourhood. India also assisted in evacuating Myanmar nationals from Wuhan, which was widely reported in Myanmar’s local media, engendering goodwill among the local citizenry.

The strategic interests underpinning Beijing’s aid to Myanmar are undoubtedly a source of concern for India, which also has critical geostrategic projects in the Southeast Asian country. One of these is the Kaladan Multi-Modal transport project, which would prospectively connect Kolkata to Myanmar’s Sittwe port. The project began in 2008, but is riddled by delays stemming from terrain to insurgency. Therefore, India is aware of the challenges and security issues arising from armed conflict within Myanmar and has nonetheless continued to pursue long-term interests with Naypyidaw. Myanmar can hence look to New Delhi as a reliable partner and decouple from Chinese dependence.

Accordingly, trust appears to be strengthening between Myanmar and India, with the former making good of its promise to apprehend Indian rebels on its soil. In a significant policy shift earlier this year, Myanmar handed over 22 militants to India. The militants belonged to separatist groups from the Northeast of India and included the United National Liberation Front (UNLF), the People’s Liberation Army of Manipur (PLA), among others. It was the first-time rebels were handed over to the Indian side, marking an important milestone in bilateral relations. “There is hope of similar episodes in the future. The real challenge is to convince Tatmadaw to unleash a more aggressive policy in the future,” said an Indian government official. Such instances indicate closer ties between New Delhi and Naypyidaw and further showcases that India can emerge as a viable alternative to China for Myanmar.

With the advent of the Act East Policy in 2014, the need to improve ties with Naypyidaw is growing. New Delhi must continue to foster better relations with Myanmar despite domestic challenges emanating from the COVID-19 virus and the ensuing economic slowdown to truly bring to fruition its neighbourhood first policy and galvanise its rising power aspiration in the international system. Providing Myanmar better aid in the midst of a pandemic is a chance to counteract deep-seated Chinese interests, thereby ‘acting east’ in the real sense.