In a globalized world, universal human rights have acquired a unique significance–not only are they markers of judging civil and political liberties in a country; they are also tools for international diplomacy.

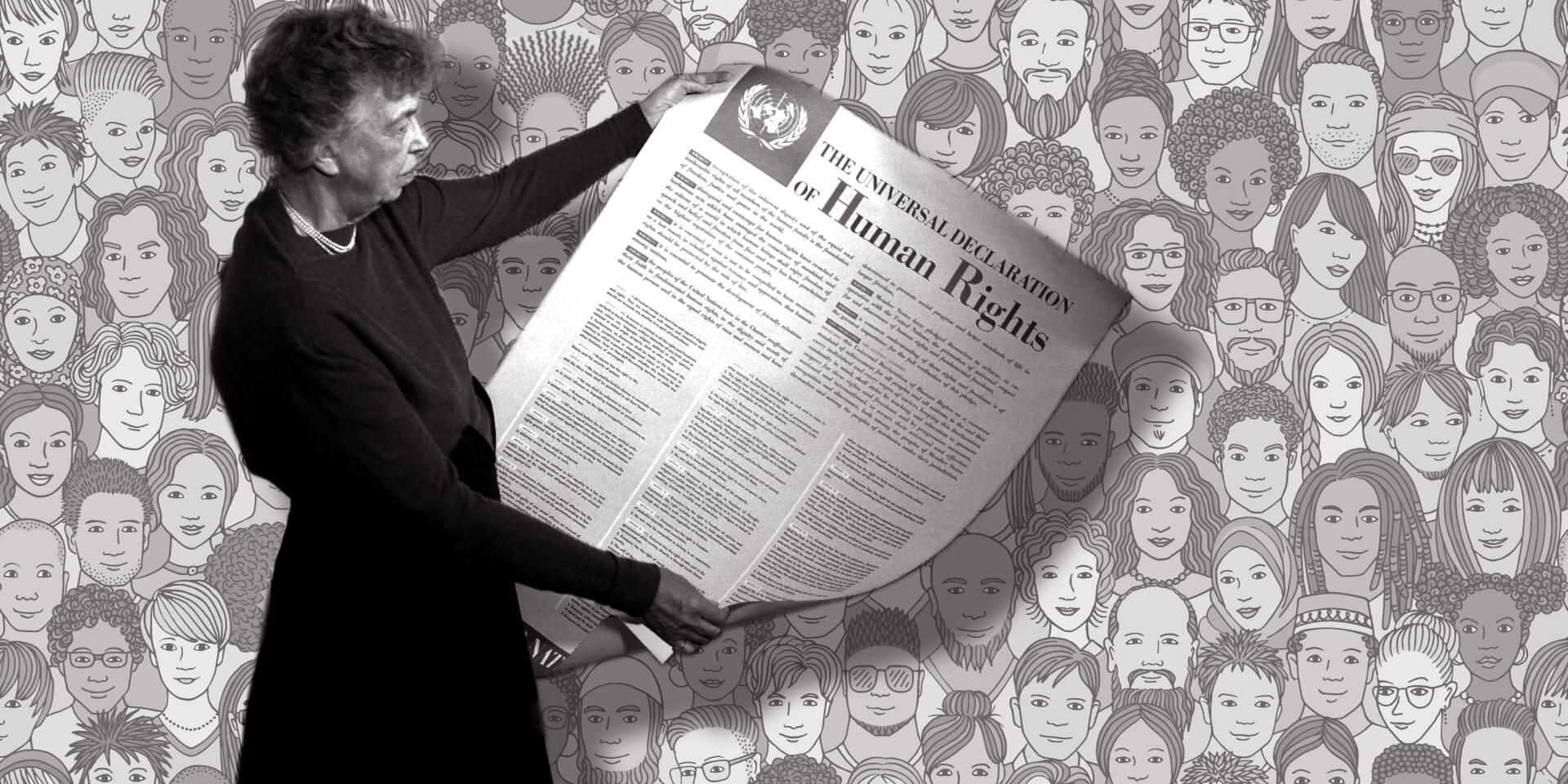

However, ever since the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948, the question of whether human rights are universal or culturally relative has been a major subject of debate among policymakers and intellectuals.

The idea that human rights are a “Western” construct and do not always fit comfortably within non-Western societies is a view that has often been driven forward by leaders in Asian, Islamic, and African countries. This notion, which stems mostly from a rejection of Western ideals in post-colonial setups, is both simplistic and factually inaccurate.

At the same time, in a truly international human rights system, there is no expectation to impose the same mechanisms to different conditions and contexts, especially in the application of human rights that deal with public order and morality, like non-discrimination. In a 1966 judgment, the International Court of Justice ruled “…to treat equally in a mechanical way would be as unjust as to treat equal matters differently.”

Source: Simon Kneebone

The main critique by cultural relativists is that those who made the UDHR were privileged Western elites whose perspectives did not reflect those of the ordinary populace. However, this is blatantly untrue–the drafting committee included representatives from Lebanon, China, the Philippines, Chile, and India.

Secondly, many relativists believe that the practice and rhetoric of human rights are reflective of Western values and principles that are individual-centric, while non-Western belief systems that are more communitarian in nature are not represented. But alternative propositions, like the 1990s’ Asian Way, have been equally ineffective.

Many governments have resisted certain international norms since they are perceived to be contradictory to their local political interests and the established cultural and social values. Furthermore, it has been argued that certain rights under the UDHR, such as the rights to marriage and religious freedoms and the private ownership of the means of production, are directly contradictory to the norms and practices in many non-Western societies.

For example, India is the largest democracy in the world and the poster-child for cultural diversity; yet, marital rape is a legalized practice which has been defended under the garb of protecting the sanctity of traditional Indian conjugal relations. Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, dominant religious groups claim that it contradicts their beliefs to recognize religious and marriage freedoms.

The Global South’s most influential ethical and religious frameworks from Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, all prescribe a deep sense of commitment to human fulfilment and the dignity of human life. All of these traditions recognize the need for justice of the common man and restrictions on authority for the greater moral good of humanity.

On the flip side, the Western conception of absolute state sovereignty, which travelled to the rest of the world through Marxism and colonialism, rejects any moral restrictions from the outside. Historically, Western states (until the Second World War) were often reluctant to accept external norms.

In what can be considered as one of the first attempts to universalize human equality, Japan at the League of Nations attempted to amend Article 21 of the Covenant with the following draft clause:

"The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord, as soon as possible, to all alien nationals as states members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect, making no distinction, either in law or in fact, of account of their race and nationality."

This was vehemently opposed by the US, Britain, Australian, Poland, and Greece because these nations felt, especially in the aftermath of the First World War, that this legal concept of international rights and equality contradicted the sovereign nature of their states which gained authority from racially and ethnically biased politics and laws. This also explains why the US pulled out of the UN Human Rights Council last year and why Australia still does not have any constitutional protection to safeguard the human rights of its citizens.

Perhaps, the UDHR is the only so-called limitation that has been imposed and accepted wholeheartedly by most Western powers with mechanisms in place for checks and balances, unlike international agreements on larger issues of defence, trade, or climate that seem to be perceived as non-binding by those who continuously breach them in the name of national security.

Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism also speaks of the sovereign nation-state as an impediment to a human being’s intrinsic ‘right to have rights’. This is because human rights only seem to be safeguarded on the basis of membership (or citizenship) to a state, while the very nature of human rights means that they transcend such constructs.

Therefore, to say that Western countries are automatically receptive to human rights due to their democratic traditions and cultural ‘superiority’ is misguided.

A major issue in human rights discourse is the severe misunderstanding of non-discrimination and related concepts in international law. Equality before the law includes the different treatment of certain persons depending on differences in their lived realities. It is not enough only to recognize everyone as equal, but to acknowledge their differences so that roadblocks to equitable living can be systematically removed.

According to the European Court of Human Rights, if there is no reasonable justification in the different treatment of a person(s) or no proportionality established between the means and the aims sought from these exercises, only then is it considered discriminatory.

For example, many East Asian policymakers have argued that the right to development is of higher priority than other rights, and that the best way for the region to ensure human rights for its citizens is to collectively move towards development, even if it means restricting their civil and political liberties. Contrarily, the US seems to emphasize civil and political rights but keeps aside socioeconomic rights since they might harm the country’s capitalist system and may infringe on autonomy.

Even the international human right to education is practised differently everywhere. In parts of Europe, free education up to the university level is offered in most countries–but for poorer countries, it may be financially unviable and unsustainable to offer free public education for all.

This is because the implementation of cultural, social, and economic rights is dependent on local circumstances, as mentioned in Article 2 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The Article states:

“Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps individually and through international assistance and cooperation...to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant...”

For actions that cause physical or mental harm to any individual or group, this is non-negotiable. However, for rights regarding public order, security, or morality, subjectivity must be maintained where the validity of the action taken should be determined before labelling it as a ‘breach’.

Article 19(2)(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights acknowledges and accepts that the right to freedom of expression is not absolute and can be restricted by law for the respect of the reputation and rights of others. So, when Arab monarchies are accused of heavily censoring their media, they are actually doing so in accordance with international law.

Hence, while all international human rights are universal and have been accepted by almost every modern state, the impact of the application of these standards is relative. Morally driven rights are not zero-sum games, and it is important to continue the tension between universalism and relativism so that entities on both sides may evolve and open new avenues for different kinds of societal changes.

In English-language literature, the use of the term ‘human rights’ has increased by 200% since the 1940s and has been utilized 100 times more than ‘natural’ or ‘constitutional’ rights. More and more people around the world are realizing that discrimination, exploitation, and oppression that have been rationalized by political/ideological/cultural myths are inexcusable, and social justice movements and protests across the world reflect this awakening.

Even international organizations are restructuring and reframing their conceptions of universal rights as more and more players from the Global South gain prominence in the international system.

Hence, it is imperative that this dissonance between the universal and the relative remains, as it only fosters growth in both directions, and the recognition of both perspectives as valid remains crucial in maintaining checks and balances of both, states and supranational actors.

Reference List

de Varennes, F. (2006). The Fallacies in the "Universalism versus Cultural Relativism" Debate in Human Rights Law. Asia-Pacific Journal On Human Rights And The Law, 1, 67-84.

Donnelly, J. (1984). Cultural Relativism and Universal Human Rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 6(4), 400-419.

Harris-Short, S. (2003). International Human Rights Law: Imperialist, Inept and Ineffective? Cultural Relativism and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Human Rights Quarterly, 25(1), 130-181.

Le, N. (2016). Are Human Rights Universal or Culturally Relative?. Peace Review, 28(2), 203-211. doi: 10.1080/10402659.2016.1166756

Oman, N. (2010). Hannah Arendt's "Right to Have Rights": A Philosophical Context for Human Security. Journal Of Human Rights, 9, 279-302.

South West Africa Case (Second Phase) (1966), International Court of Justice 284.