The farmers’ protests have struck a chord with populations across various demographics, with civilians and politicians both within and outside India praising the demonstrators’ unwavering determination and appreciating the invaluable fruits of their labour. Against this backdrop, several commentators have debated the merits and drawbacks of the newly-introduced bills that instigated these protests. In fact, even prior to this latest uprising, India had already been witnessing increasingly frequent protests, demonstrating the need for a drastic change in the country’s agriculture industry. However, amidst this growing unrest among farmers, one of the less addressed and acknowledged points is that India simply has too many farmers, and this issue needs to be addressed expeditiously.

Some of this can be attributed to social hierarchies, caste, and the fact that certain professions are passed down from one generation to the next. On one hand, the new bills arguably could indeed have been deliberated over more intensely and included farmers in the consultation process, especially given that the agriculture industry is the driving force of the country, employing millions of people. Deregulation may leave several already impoverished and indebted farmers even more vulnerable, further compounding the mounting crisis of farmer suicides. While the newly introduced bills could arguably bring in the necessary changes to reform the agricultural industry, they fail to address the need to focus on diversification of India’s labour market. The fact that there are so many farmer suicides and so many impoverished farmers may suggest that the industry itself is overcrowded. However, the reforms introduced by the government put the cart before the horse, in that they seek to achieve this long-term goal without first addressing the immediate concerns of citizens who are still employed in the agriculture industry.

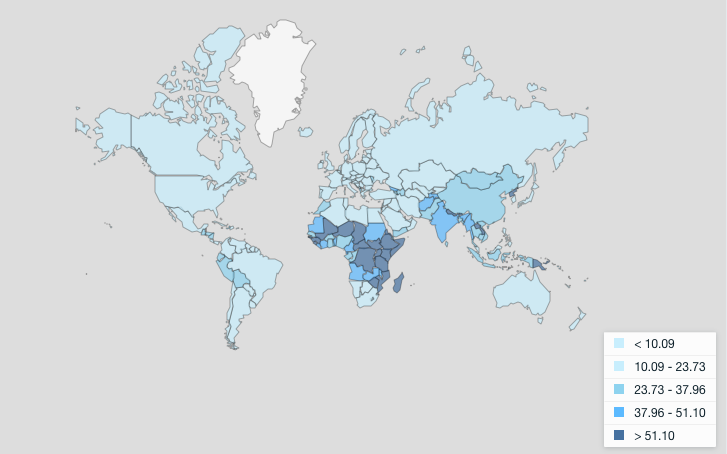

Most developed countries have proactively diversified their job market to reduce their reliance on agriculture. Since the early fifties, economists have established that for developing countries to evolve from a backward agriculture-centric economy, they must shift towards industrialisation. This trend is clear from the recent data published by the World Bank in September 2020, which clearly shows that, since 1991, the percentage of people worldwide who are employed in agriculture has steadily decreased. On further analysis of the data, it becomes increasingly evident that the populations of richer or more developed economies are the least dependent on agriculture for employment. For instance, in the United States, merely 2% of the population is employed in agriculture. On the other hand, countries like Afghanistan, who are generally thought of as weak economies, have seen the smallest percentage of a shift from employment in agriculture to other industries.

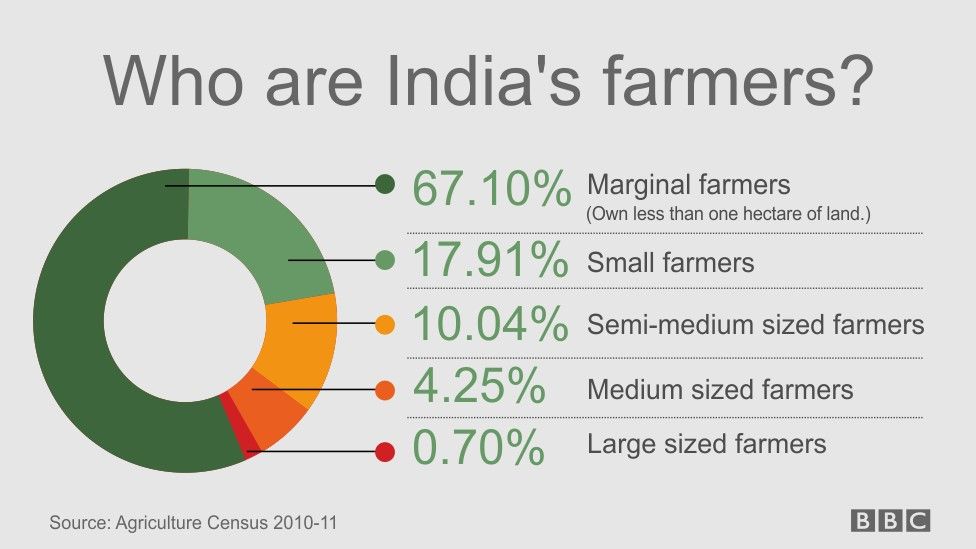

India is no different. With its economy growing and an increasing number of citizens focussing on education with the desire to migrate to urban areas, the aspiration of the Indian workforce to shift from agriculture is evident. This has been driven by the lack of opportunity and growth that taints the agricultural industry. Furthermore, while previously farmers were prosperous owners of vast fertile lands, now, according to the National Sample Survey Organisation, the average size of a farm is merely 0.2 hectares. With the groundwater levels depleting, the sizes of farms reducing and the fertility of soil decreasing, the cost-to-yield ratio has nosedived. These developments have essentially forced India to diversify its job market.

Yet, in spite of mass migration to urban areas, India continues to be highly dependent on agriculture for employment. In fact, around 50% of India’s total workforce continues to be employed in agriculture-related employment. Combined with the fact that agriculture contributes to merely 15% of India’s GDP, it is clear that this overreliance on agriculture is problematic, to say the least. This has precipitated a monumental downfall in per capita income in the industry, leaving many impoverished and straddled by debt.

However, despite the apparent need for diversification of the job market in India, political motivations continue to drive the Indian government’s actions when it comes to agriculture, especially considering the proportion of voters that are either farmers or employed in agriculture-related activities. This has motivated policymakers to disincentivise the modernisation and mechanisation of agricultural practices and push for a continued reliance on manual labour. For example, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA), which was passed in 2005, reads: “As far as practicable, a task funded under the Scheme shall be performed by using manual labour and not machines.” Hence, rather than promoting technological solutions that make farming activities more profitable and less labour intensive, governments have sought to increase reliance on agriculture-based employment despite clear evidence of its harms. In the short-term, this maintains jobs; in the long term, however, this leads the overcrowding of the industry, which not only reduces per capita income but also impedes the advancement of India’s economy.

This lack of political will has led to a stagnation in agricultural policymaking in the country. The current regime, which focuses on food production and not on making agriculture a lucrative business, has been in place since the 1960s. When the policy was first formulated, the focus was on ensuring food security, wherein the aim was to incentivise production and secure access to affordable food. Now, with the onset of the green revolution, the inadequate supply of food is not as much of a concern; instead, the issues that continue to burden the agricultural industry and farmers are those of fluctuations in demand, lack of cold storages for perishable produce, and difficulties in transportation.

However, the continued prioritisation of political motivations has led to various calls for reform being significantly watered down or rejected entirely. Most recently, in 2018, the Dalwai committee called for a shift in the policy from a production-centred one to one that is demand-focused and market-based in order to increase the incomes of farmers. However, there has been no action taken by the government to implement the recommendations out of fear of resistance from the community. Similar recommendations made to the Indian National Congress-led government by the Swaminathan Commission in 2004 also met with the same fate. The Commission recognised the importance of urbanisation and called for infrastructure development in pursuance of this. However, like the Dalwai committee, there was no tangible progress made in the furtherance of these recommendations. This is primarily driven by the age-old fear that policy changes in agriculture will inevitably result in political backlash from farmers, who have historically been resistant to drastic policy changes and the modernisation of their industry.

Nevertheless, the impact of not introducing gradual changes over the years that adapted to the evolving agricultural needs of a country is now being felt. Decades of inaction have now necessitated an overwhelming transformation that cannot be delayed any further, which has invariably created an unprecedented level of disharmony among farmers. Regardless of the necessity for reform, by delaying the implementation of such policies for so long, the Indian government has created an overcrowded industry with underpaid workers who are essentially forced to continue digging an even deeper hole for themselves due to the lack of viable, visible, and accessible alternatives.

The importance of the timely introduction of bold steps to shift the Indian labour market’s reliance on agriculture can neither be denied nor ignored. There is a need for Indian policymakers to push for the diversification of the Indian job market to make it match the industries’ contribution to the economy, which will ultimately increase the per capita income of farmers while also modernising India’s economy. This is particularly challenging, as the demands of farmers cannot be ignored. Not only do they form a significant chunk of any vote bank, but they are also crucial for protecting India’s food security. Hence, it is a sticky situation for political leaders and legislators, who are not only being pressurised to spearhead much-needed reforms but are also faced with vociferous opposition at each step. This, combined with the risk of endangering their political ambitions, is a significant obstacle for any government looking to bring in drastic changes and realign the Indian labour market.