On November 18, 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was sworn in as the president of Sri Lanka, and three days later, he appointed his brother Mahinda as the prime minister (PM). Their re-emergence in the upper echelons of Sri Lankan politics came after last April’s Easter bombings in Colombo by Islamic terrorists, which left 259 people dead. Just six months before the elections, these tragic events fuelled a resurgent wave of Sinhalese nationalism that was both capitalized on and reinforced by the Rajapaksas in their election campaigns. Eleven years on from the end of the 26-year civil war and the Mullivaikkal massacre, Sri Lankan Tamils, who form 11% of the population, are holding on to their loved ones just a little bit tighter after the government was thrust back into the blood-soaked hands of two of the chief architects of the Tamil genocide.

During the civil war, between 70,000 to 140,000 Tamils, who refer to Sri Lanka as Eelam, were murdered, and over 300,000 were displaced. This decades-long conflict was marked by human rights abuses by both Sri Lankan forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Several Tamil civilians were extrajudicially killed and routinely murdered, raped, tortured, and even abducted and then fed to crocodiles, while the LTTE is known to have attacked civilian targets and recruited child soldiers. Caught in the crossfire were innocent Tamil civilians, with at least 40,000 killed in the Mullivaikkal massacre during the final stages of the protracted conflict. Prior to this massacre, with the armed forces sensing victory over the LTTE, the government purposely misled Tamil civilians by ordering them into “no-fire zones” with the promise of shelter, where thousands were then indiscriminately tortured, raped, mutilated, and shot at. In the aftermath of the war, it was estimated that over 20,000 Tamils had gone ‘missing’. In January 2020, President Gotabaya finally admitted to a UN envoy that they were all dead. The sheer brutality of the Sri Lankan army’s actions—which amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity—has been documented by the United Nations (UN), Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the Public Interest Advocacy Centre, and others. Puppeteering these acts of genocide were Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was President at the time, and his brother Gotabaya, who was the defense secretary.

Over a decade later, while the dust continues to settle on crimes committed by Sri Lankan authorities, the tears of Sri Lankan Tamils have yet to dry. Eelam Tamils continue to traverse the rocky path towards justice for the various crimes committed against them, and with the ominous cloud of the Rajapaksas now looming over them once more, this road has only gotten longer.

The wheels that have driven reconciliation and justice beyond the reach of Tamils were set in motion in advance of the Mullivaikkal massacre. In anticipation of a brutal and ugly conclusion to the war, the Sri Lankan government ordered international humanitarian organizations, such as the UN, to withdraw from the war zone. In the absence of international watchdogs, authorities under-reported the number of civilians in shelters and camps so as to reduce the amount of humanitarian aid given, and then restricted the deliveries and failed to provide safe passage for that same aid, resulting in thousands of deaths from lack of food and medical care. Moreover, hospitals were hit with “aerial and shelling attacks” at least thirty times during the last five months of the conflict, meaning that even those who were lucky enough to receive medical aid ran the risk of being targeted once more.

There was a semblance of hope under the President Maithripala Sirisena, who preceded Gotabaya, when he co-sponsored a resolution in which he and 11 other countries agreed to a UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) investigation of war crimes, promising “transitional justice”. The investigation was to consist of four arms: “an office of missing persons; an office for reparations; an accountability mechanism with international judges, lawyers and investigators; and a mechanism for truth and reconciliation”. While progress was indeed limited and largely symbolic, an office of missing persons and an office for reparations were established. Indeed, while it may have been a campaign ploy, Sirisena also initiated power-sharing endeavors with minorities and even reduced the ambit of presidential powers through the 19th Constitutional Amendment.

However, come November 2019 and the victories of the Rajapaksa brothers, even these piecemeal and minimal steps towards reconciliation and justice were dismantled. In February of this year, Minister of Foreign Relations Dinesh Gunawardena issued a statement saying: “I wish to place on record, Sri Lanka’s decision to withdraw from co-sponsorship of Resolution 40/1 on Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka.” He said that while Sri Lanka remains “committed” to facilitating “sustainable peace and reconciliation”, this would be through a locally-managed process. PM Mahinda decried the “historic betrayal committed” by the Sirisena government in partnership with the United National Party, the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) and the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) party to co-sponsor the UN Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1. Meanwhile, both brothers have sought to repeal the 19th Amendment, which reduces the Presidential term limit from six years to five years, institutes a two-term limit, and places restrictions on when the President can dissolve Parliament.

Aside from undoing some of the progress made under the previous government, the Rajapaksas have also sought to institute their own reforms that further undermine national unity and Tamil identity and representation. Just four years after the government decided to play the national anthem in both Sinhalese and Tamil in order to engender togetherness, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced that the policy had now been scrapped. To distance Tamils even further from political discourse, there are only two Tamils in Gotabaya’s 51-member Cabinet, which is disproportionate to the demographics of the country.

These actions are compounded by the fact that the current administration continues to celebrate its genocidal soldiers as ‘war heroes’. On the eleventh anniversary of the end of the civil war, Gotabaya said, “In a small country like ours where our war heroes have sacrificed so much, I will not allow anyone or organization to put pressure on them and harass them. We will not hesitate to withdraw from any organization or agency if our war heroes are targeted”. Gotabaya has even spoken of granting immunity and clemency to soldiers accused of war crimes. He made true on his promise in March, when he pardoned and released Staff Sergeant Sunil Ratnayake, who was on death row for murdering eight Tamil civilians in 2000, including a five-year-old child and two teenagers. The dictatorial undertones to the Rajapaksa dynasty were evinced by Nimal Siripala de Silva, the Minister of Justice, Human Rights and Legal Reforms, who said, “The final decision is with the President. He can overrule anything. He has the absolute power to grant pardon, no one can question him.” Thus, given their penchant for glorifying the bloodiest chapters in Sri Lanka’s history, it inspires no confidence when Mahinda attempts to reassure Tamil leaders that he will discuss the release of Tamil political prisoners with his brother.

This mistrust is cemented by the fact that there is increasing militarization in the Northern and Eastern provinces, where the majority of Tamils live. Sixteen of the Army’s nineteen divisions are stationed in these two provinces, and several cities with high concentrations of Tamils have a ratio of one soldier to every three civilians, while the average soldier to civilian ratio across the entire country is just one to fifty. This imperious overwatch is made possible by the fact that, since the end of the civil war, the military’s numbers have doubled from 200,000 to more than 400,000. Moreover, the hatred which fuelled the civil war evidently still plagues the military, as evidenced by the poignant image of Brigadier Priyanka Fernando making a throat-slitting gesture at Tamil protestors outside of the Sri Lankan High Commission in London in 2018.

There has also been an increase in surveillance on and harassment of Tamil activists and politicians. For example, the offices of the Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF) are routinely encircled by armed soldiers. Ahead of the Mullivaikkal Remembrance Day, a judge ordered senior TNPF leaders into isolation, with the bogus claim of disease control and prevention. The home of the lawyer who successfully appealed this order was then attacked. Similarly, a Sri Lankan court barred TNA, TNPF, and the Uthayan Tamil newspaper from holding Tamil genocide remembrance day events in Jaffna, a decision which was then enforced by the army. Aside from these legal repercussions, the Sri Lankan police have warned TNPF members that they would shoot them if they lit candles to commemorate the eleventh anniversary of the genocide, while PM Mahinda has alarmingly declared that all Sri Lankans must “pull together or perish”.

Likewise, Tamil property, temples, and cemeteries are being destroyed, often to make way for Buddhist viharas, or monasteries. While many of these events pre-date the Rajapaksas, the perpetrators of these acts have only grown more brazen in the face of the brothers’ re-ascent on the Sri Lankan political ladder.

Human Rights Watch reports that the families of the more than 20,000 ‘forcibly disappeared’ Tamils, who Gotabaya has now admitted are all dead, are still being subjected to “government surveillance and intimidation”. In addition, while the government has opened legal proceedings against Tamil activists and politicians, it has put a stop to similar proceedings against the officers accused in the ‘enforced disappearances’ cases. Simultaneously, over 700 criminal investigators looking into such matters and indeed the Rajapaksas have now been slapped with travel restrictions. Concurrently, the offices of media outlets that are critical of the brothers have regularly been raided on false accusations of hate speech, and Tamil reporters have been “censored”, “attacked”, and threatened.

These intimidation tactics and negation of history have not only been reserved for Sri Lankan citizens or residents of the island nation.

For instance, it has emerged that a Sri Lankan employee at the Swiss Embassy in Colombo was abducted and forced to surrender “sensitive embassy information” on citizens who are seeking asylum in Switzerland following the Rajapaksas’ presidential and prime ministerial victories.

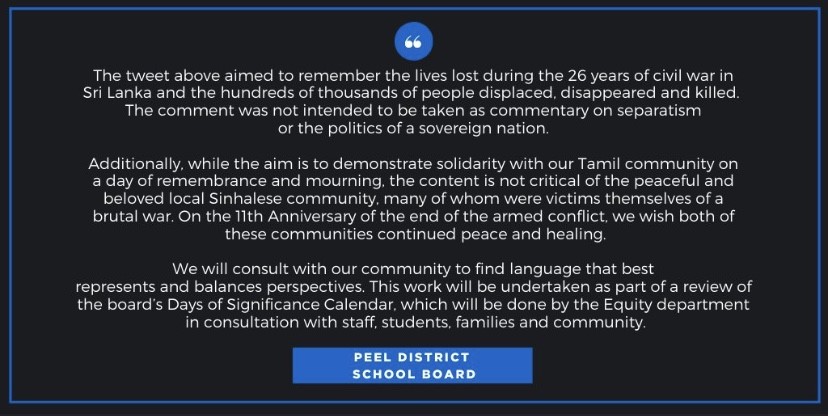

In Canada, the Peel District School Board tweeted on May 18: “Today is Tamil Genocide Remembrance Day. We honor the innocent lives that were lost, those who were displaced, and those who suffer trauma to this day.” Almost immediately, the Board was forced to massage the fragile egos of the “peaceful and beloved local Sinhalese community” after the Sri Lankan embassy and the Canadian Sinhala community rallied and gathered the signatures of over 20,000 petitioners to “reject any proclamation of Tamil “Genocide””.

Even global news outlets have not been spared the wrath of the Sri Lankan Government. In May, the Guardian asked, “Eelam is an indigenous name for which popular holiday island?,” in a travel quiz. Eelam is the native Tamil name for the island of Sri Lanka; however, Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner to the UK wrote to the publication saying that “Eelam has never been used as an indigenous name for Sri Lanka” and denounced the newspaper for a “sinister attempt to propagate the ideology of a proscribed terrorist outfit”. Under this pressure, the Guardian took the question down.

It thus rests on international actors like India, Canada, the UK, Germany, France, Switzerland, and Australia, which all have large amounts of Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora and refugees, to form a renewed push for an investigation into war crimes and create pressure on Sri Lanka to engender reconciliation among Eelam Tamils.

During a meeting with his Sri Lankan counterpart Mahinda in February 2020, Indian PM Narendra Modi said, “I am confident that the Government of Sri Lanka will realize the expectations of the Tamil people for equality, justice, peace, and respect within a united Sri Lanka.” India holds a strong ethnic connection with Sri Lanka, given its own 80 million-strong population of citizens in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, and the fact that it has taken in over 100,000 Sri Lankan Tamil refugees. India has also built over 44,000 houses in the Tamil-majority Northern and Eastern provinces. At the same time, India also wields significant bargaining power in its relations with Sri Lanka. For instance, during his February visit, Mahinda asked Modi to defer Colombo’s debt repayment for three years, and also discussed an additional $400 million Line of Credit.

Similarly, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has mourned the loss of thousands of Tamils during the civil war, and called on the Sri Lankan government to “fulfill its international and domestic commitments to establish a meaningful accountability process that has the trust and confidence of the survivors”. He added that “Canada continues to offer its full support to the Government of Sri Lanka and all those working toward accountability, justice, peace, and reconciliation on the island”. In addition, Gary Anandasangaree, a Toronto-based Liberal parliamentarian of Tamil descent, has leveled that the Sri Lankan government has not sufficiently addressed human rights abuses. Likewise, Brampton mayor Patrick Brown has described the Peel School District Board’s apology to the city’s Sinhala community for commemorating Tamil genocide as “disappointing”, saying that the Board “should not tweet to commemorate a genocide and then apologize to the oppressor”.

Likewise, during his visit to Sri Lanka in 2013, former UK PM David Cameron met with Tamil leaders and refugees in the Northern Province and also flagged the Kingdom’s concerns over human rights abuses by Sri Lankan forces during the civil war. The current PM, Boris Johnson, has said that he “hopes there will be reconciliation in Sri Lanka, accountability for what has gone before us, what’s happened in the past”.

The UN, too, has passed three resolutions that urge the establishment of war crimes investigations. However, none of the aforementioned countries or the UN have referred to the treatment of Sri Lankan Tamils as genocide. Photographer and former UN staffer Benjamin Dix, who was present in Sri Lanka during the civil war, has said, “It is very fair to say that the Army committed genocide. The atrocities in Sri Lanka were definitely towards ethnic cleansing.” He added, “The Sri Lankan Army does not believe that they committed atrocities. It is a propaganda that they liberated Tamils from the Tamil leadership. It was not a liberation, but [the] destruction of the Tamil community.”

The UN, and India in particular, are complicit in the actions of the Sri Lanka government and armed forces. A former UN staff member, on a visit to Sri Lanka in February 2009, prior to the final stages of the war, was “very seized” by the exponential growth in civilian casualties and told his seniors that the UN “would be complicit if we do not act on it”. However, his warning was not heeded, and UN staffers suspended their count of casualties just days before the Mullivaikal massacre, and even put out statements that supported the government’s account of the events, wherein the LTTE were presented as uniquely responsible for atrocities committed during the civil war, even in the face of widespread evidence of genocide by the Sri Lankan army. Likewise, the Indian army provided logistics, weaponry, and training to their Sri Lankan counterparts, which indirectly contributed to the loss of thousands of Tamil lives. India’s complicity makes it highly unlikely that it will accelerate its demand for justice as it would simply result in more attention on its role in the conflict.

Indeed, Mahinda has already rebuffed Modi’s call for Sri Lanka to implement the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prescribes the devolution of certain powers to provincial councils in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, such as policing powers and control over “land from the unitary state”. Mahinda has emphatically said that any resolutions that are “not acceptable to the majority community” of Sri Lanka will not be fulfilled, once again reaffirming his commitment to Sinhala nationalism, at the expense of reconciliation for Tamils.

Aside from India, Sri Lanka has already repeatedly rebuffed calls from other international actors and organizations to launch or participate in investigations into war crimes and crimes against humanity. At the same time, even if India were to press for such an investigation, Sri Lanka is seemingly weaning itself off of Indian support and moving into the arms of China with the signing of the Hambantota Port and loan deals with China. In the past, China has advanced the goals of one of its other Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) partners, Pakistan, wherein it protected the Jaish-e-Mohammed terror group leader Masood Azhar from being blacklisted by the UN Security Council (UNSC) as a global terrorist. Hence, it is possible that China would lend similar support to Sri Lanka as well, shrouding the government and the Rajapaksas from accountability.

Ultimately, as former US ambassador to Sri Lanka Patricia Butenis said in a leaked cable from January 2010: “There are no examples we know of a regime undertaking wholesale investigations of its own troops or senior officials for war crimes while that regime or government remained in power.” Even at the time, she said that any international clamor for prosecutions and investigations would merely result in Rajapaksa and his allies doubling down on their “super-heated campaign rhetoric [...] that there is an international conspiracy against Sri Lanka and its ‘war heroes’.” So long as the Rajapaksas remain in power, justice for the crimes committed by Sri Lankan authorities during the civil war and reconciliation for Sri Lankan Tamils, both at home and abroad, will remain elusive.

The Wounds of Sri Lankan Tamils Can’t Heal So Long As the Rajapaksas Are in Power

The brothers rose to power during a resurgent wave of Sinhalese nationalism in 2019.

July 5, 2020

IMAGE SOURCE: APPrime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa (left) and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa (right)