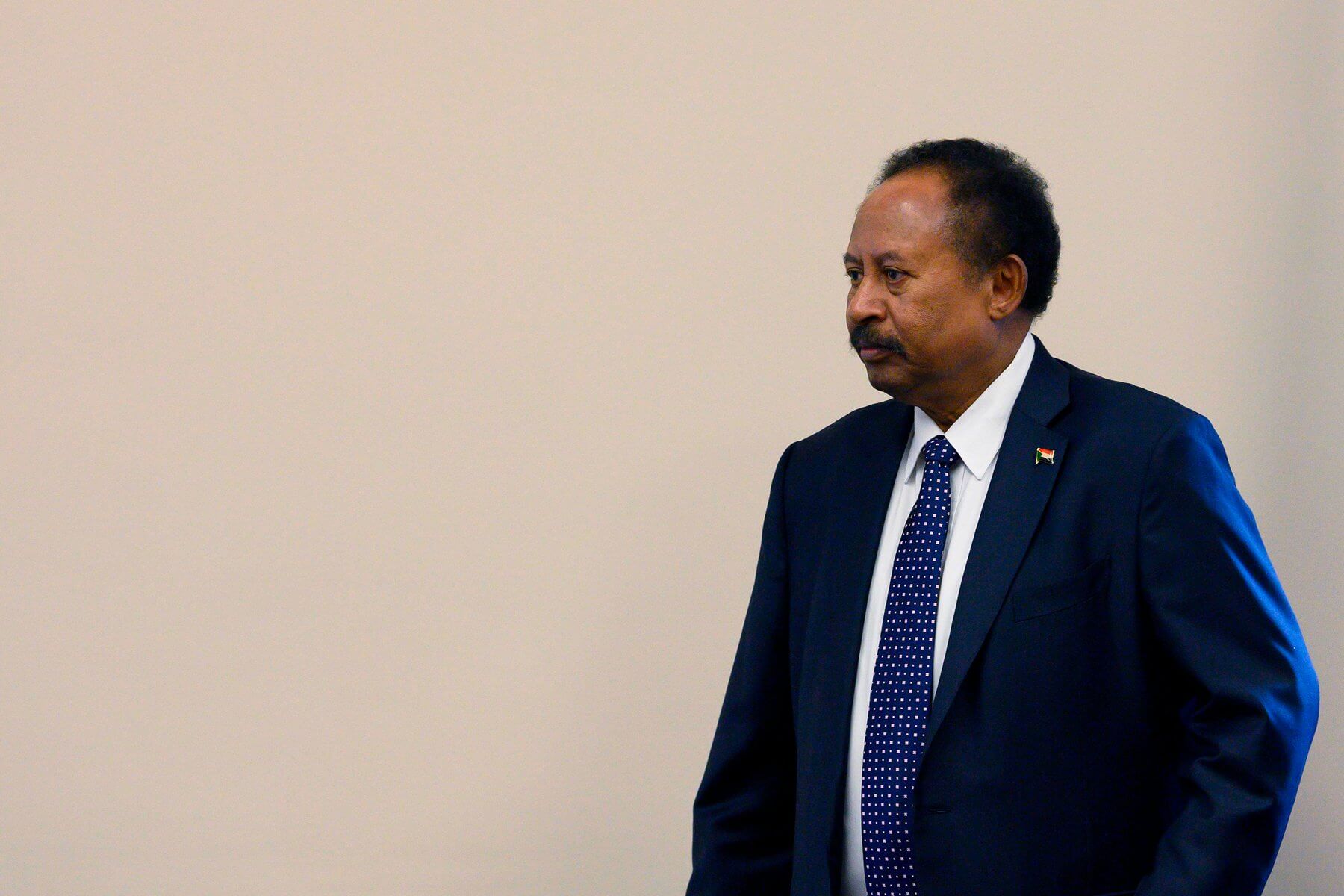

It has been a little more than a year since Sudan’s long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir was ousted from power after a 30-year reign, in what can only be described as an extraordinary revolution. In the time that has followed, Sudan’s transitional government—headed by a council of civilian and military representatives and led by former UN economist-turned-Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok—has worked to swiftly dismantle the toxic legacy that Bashir left behind and move the country forward through sweeping social and legal reforms.

This has included the repealing of a number of laws used to regulate women’s behaviour in the country, criminalizing female genital mutilation (FGM), ending punishment by public flogging, and easing restrictions on the sale and consumption of alcohol. Most recently, the leadership also signed a peace deal with Sudan’s primary rebel union—the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF)—which reportedly covers important issues regarding land ownership, security, power-sharing, transitional justice, and the repatriation of those who fled their homes during the war, and also contains provisions to dismantle rebel fighters and integrate them into the national army.

However, despite these gains, the issues that first triggered protests across the nation last year continue to plague Sudanese society. Extreme economic fragility to due rampant inflation and a near-bankrupt government has left the government unable to provide for its citizens. To help address this problem, the Sudanese leadership has called on the international community, stressing that significant debt relief and investment into the poverty-stricken country are important prerequisites to overcome the remaining obstacles. However, there remains one major roadblock to progress on this front: Sudan’s designation on the United States’ (US) State Sponsors of Terrorism (SST) list.

The US’s SST was created in 1979 to designate countries that had “repeatedly provided support for acts of international terrorism”. Sudan’s name was entered on the list in August 1993, not only due to former President Omar al-Bashir’s government’s ties to a wide range of Islamic extremists such as the Abu Nidal Organization, the Palestinian HAMAS, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the Lebanese Hizballah, and Egypt’s al Gama’at al-Islamiyya but also because the US said that the country served as a safe haven for Iranian-backed jihadist groups and was extensively propagating anti-US rhetoric through its foreign policy agenda. After the 1998 attacks on US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, the US began keeping a close eye on Al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, who was found to have taken refuge in Sudan from 1991-96, prompting even harsher measures from the US.

However, things are drastically different today, and, since Bashir’s removal, the Sudanese leadership has emphasized that the country shouldn’t be punished for crimes committed by the previous regime. Unlike other nations on the SST list, which include Syria, Iran, and North Korea, Sudan actually has a responsible government that is keen to move forward, and last year’s revolution was fundamentally opposed to the sort of militant Islamist ideology that has in the past polarized and impoverished the country. It has even done its part to comply with the US’s requirements for its removal.

One of the biggest points of contention was Sudan compensating the families of the victims of the 1998 terror attacks and the 2000 bombing of USS Cole in Yemen that were supported by Bashir’s government. On this front, in February 2020, the Trump administration reached an agreement in principle with the Sudanese leadership, who has agreed to pay the $335 million. The country has also taken efforts to improve humanitarian access within its borders, instituted new and progressive social reforms, and has supported American and international counterterrorism efforts, all the while showing that it no longer sponsors terrorism. Though these improvements led to the lifting of most unilateral US sanctions on Sudan in 2017, its removal from the SST still remains a challenge, despite a significant normalization between the two sides, and the US even supporting the new Sudanese government.

While the Obama government held out from delisting Sudan because of its poor human rights record and its history of authoritarianism, the Trump administration’s refusal to move ahead in the process shows lethargy, or even worse, the lack of understanding within the US leadership of the implications of delaying updating Washington’s policy towards Khartoum.

In fact, aside from not recognizing the true impacts of blacklisting Sudan, US leadership has also shown an alarming lack of knowledge about the nature of the Sudanese government. In an August 25 meeting between US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Sudanese PM Hamdok, the US also urged Sudan to establish ties with Israel, only to be told that that the transitional government did not have the mandate to decide on such major issues relating to foreign relations.

This form of tunnel-vision is derived from the contractual nature of the Trump administration’s foreign policy, wherein it holds countries hostage to achieve more overarching goals, particularly ahead of the November elections. For example, the US insists normalization of ties with Israel in virtually all negotiations with actors in the region, despite Sudan asking the US to keep delisting separate from the issue of Israel.

While Washington continues to employ this faulty approach towards Khartoum, the coronavirus crisis has further plunged Sudan into the deep recesses of a crumbling currency, spiraling prices, and increasing unemployment. Sudan even declared an economic state of emergency earlier this week. Though the transitional government has said that it will set up special economic courts and institute stronger currency controls as well as crack down on the black markets and illegal traders in an effort to address the crisis, international help will be needed to bring some semblance of stability to the country. However, due to its designation, Sudan cannot seek debt relief and financing from Bretton Woods institutions like the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The country has a real chance to move towards becoming a stable democracy and economy if its internal reforms can be complemented by external financial and technical support. The US must recognize that helping Sudan is in its interests because the current economic crisis (coupled with the fallout from COVID-19) and the continuing security challenges have the potential to completely bury the transitional government, and push the country back into crippling instability, which could ironically pave the way for anti-US forces to once again take hold in Sudan. Hence, establishing strong support for the civilian government is the best way for the US to curb the resurgence of an outfit like the old regime in the country and its support for terrorists.

US action on this front could also in fact increase its leverage and allow Washington the opportunity to shape an outcome for Sudan that aligns with its own security interests. Not just that, but quite simply, the SST designation is no longer reflective of Sudan’s behaviour. The delisting process itself is lengthy and requires approval from Congress after a six-month review, but if the US signals its willingness to initiate the process, it could incentivize the international community and other US allies to look more seriously into providing more sustained crucial assistance to a country desperately fighting to give democracy a chance.

The US Must Remove Sudan From Its Terror List. Here’s Why.

The country has a real chance to move towards becoming a stable democracy and economy if its internal reforms can be complemented by external financing and technical support.

September 17, 2020

Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok SOURCE: THE NEW YORK TIMES