For years now, security analysts all over the globe have been wary of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, especially in the Persian Gulf. Ever since the United States (US) withdrew from the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018 and slammed crippling sanctions on Iran and its oil exports, tensions in the region have increased, as Tehran refuses to back down from its proxy wars in the region even in the face of a terrible economic crisis. And while the prospect of a direct and open conflict seems highly unlikely in at least the near future, the threat of nuclear escalation is growing increasingly real, as Gulf powers Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have officially begun to develop nuclear energy of their own. In this regard, it is important to look at the geopolitical factors at play that may affect the Gulf’s intentions and ability to develop nuclear arsenal from what are right now being presented as civilian facilities.

In the recent past, adversarial lines within the Persian Gulf have moved on from just being bound to the historical, sectarian, and ethnic rivalries between the Arabs and the Iranians. Interestingly, historical rivalries with Israel are also thawing to strengthen a mainly Saudi-led, US-backed coalition against an Iranian-Russian axis that is backed by the Iran-allied Lebanese Hezbollah forces in Syria and the Houthis in Yemen.

Increasing nuclear ambitions in such a volatile part of the world have concerned experts, who are wary of Iran’s blatant disregard for international norms, rules, and regulations set by the JCPOA, and its denial of access for assessments by the United Nations nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Announcements by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia to shift to more nuclear-dependent energy sources in bids to diversify their oil-driven economies has added a layer of worry to international analysts monitoring the region.

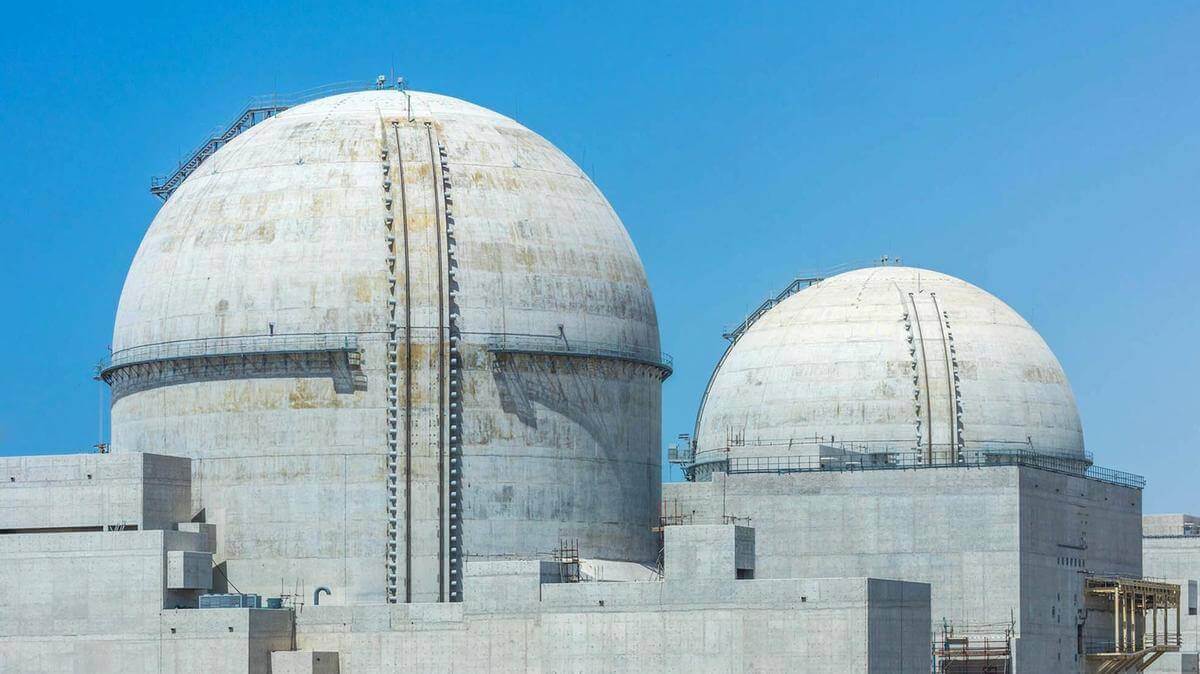

Most recently, the UAE, a staunch US ally as well as the first Arab Gulf state to officially declare the normalization of diplomatic ties with Israel, inaugurated four new nuclear reactors at the first nuclear power station in the Arabian Peninsula, the Barakah. The reactor, which was reportedly launched years behind schedule due to construction and budgeting issues, has been developed in agreement with the IAEA’s Additional Protocol, which allows the agency to enhance its inspection capabilities in the country. Abu Dhabi has also made a firm commitment that its intentions with the plant are peaceful, stressing that it will not enrich uranium or reprocess any spent fuel at the plant. Further, the Barakah has also managed to secure the 123 Agreement with Washington, which is a crucial approval that can pave way for bilateral cooperation for civilian nuclear capabilities, including the trade and transfer of nuclear training, equipment, materials, and components.

Paul Dorfman, the founder of the Nuclear Consulting Group and an advisor to several governments on nuclear radiation risks, said that the Barakah is simply “the wrong reactor, in the wrong place at the wrong time”. This is because the UAE has several options for renewable energy that are far cheaper and more sustainable, given its climatic realities and conditions. And while Abu Dhabi has also announced that it is building the world’s largest solar energy centre, the real motivations behind spending billions on a nuclear fission facility for electricity generation when it could just invest more in safer and cheaper options are worrying nuclear energy experts like Dorfman who believe that the Emirates’ decision to continue with a significantly more expensive option may signal their interests in nuclear weapon proliferation, hidden in plain sight as civilian construction.

Similar to Abu Dhabi, Riyadh also insists that its nuclear ambitions are limited to civilian energy projects; however, it differs from Abu Dhabi in that it has not officially sworn off developing nuclear weapons. In fact, despite credible concerns of proliferation, the US has supported the Kingdom in its nuclear endeavours.

But, the Saudis have been rather secretive about their planned nuclear project, which was announced in 2018. Satellite images published by Bloomberg earlier this year have revealed that the Arabs have built a roof over their reactor at the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology in Riyadh. This development has also alarmed nuclear experts since the Saudi administration has not invited the IAEA to inspect the reactor or monitor the site.

To further complicate the geopolitical alliances in the region, a recent Wall Street Journal article revealed that, as per a deal with Beijing, Riyadh would be constructing a facility to extract uranium yellowcake. The facility has not yet been publicly disclosed but is rumoured to have begun construction near the sparsely populated desert city of Al Ula, located in the country’s north-west. The move is also likely to cause alarm in Israel, whose officials have closely monitored Riyadh’s nuclear progress. In response to the news about the secret facility, Berlin just yesterday urged Riyadh to comply fully with the terms of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), of which the Kingdom is a signatory.

Even though WSJ reports that Riyadh is not even close to the point of developing nuclear weaponry, the exposure of the facility has appeared to draw attention and alarm in the American Congress, where lawmakers have expressed their concern about its growing nuclear energy goals. These worries are grounded in recent development and in Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s 2018 statement, in which he vowed that the Kingdom would “follow suit as soon as possible” if its adversary Iran successfully developed nuclear weapons.

This Chinese alliance also stands to jeopardize Riyadh’s relations with Washington, as the US-China rivalry continues to escalate. So far, China has chosen to ignore Gulf countries’ close relations with the US in its dealings and investments, despite being a close ally to Iran. Currently, Saudi Arabia is also a large beneficiary of American arms—in a recent report by an American government watchdog, it was revealed that the US State Department had bypassed Congress to hasten a multi-billion dollar arms deal with the Kingdom. Favourable posturing towards Beijing, especially in security and defence ties, for which it has traditionally been reliant on Washington, therefore, may thwart its existing strategic alliance in the West.

Another crucial aspect to consider is the power dynamic within the Gulf. While the Saudis and Emiratis are known commercial business competitors, they also find themselves with divergent military and security interests in Yemen, a conflict that they were initially allies in. Now, the UAE supports the separatist Southern Transitional Council (STC), while Saudi continues to back the government fighting Iran-backed Houthis. The increasing competition between the two neighbours and the haste by which they are securing foreign deals for nuclear energy signals the possibility of the beginning of a nuclear power race between the two states.

Therefore, the instability in relations and diverging alliances in the region have made the introduction of civilian nuclear energy highly problematic, especially since Riyadh has refused to allow the IAEA to conduct thorough checks at its facilities, despite pursuing a comprehensive program with the body, having a representative on its board of governors and pushing for the same strictness to be applied to Tehran. This is a crucial step to ensure that regulations and surveillance are done in accordance with internationally-recognized non-proliferation treaties. Put simply, keeping the body away would further increase global doubt regarding enrichment and the domestic dealings regarding substances that flow out of such reactors.

If the issue is one of the economy alone—i.e., diversifying away from petroleum-dependency for energy and trade—environmental experts have argued that nuclear power proves to have far more potential risks on ecological, climatic, radioactive, and geopolitical levels. These worries have been elucidated on by experts such as Carnegie Endowment fellow Dr Cornelius Adebahr, who said, “The threat of a regional arms race is real… for regional politics, the question will be about nuclear enrichment and non-proliferation. ”

Currently, the UAE has emerged as a regional leader in the Gulf, and the Middle East in general, with unwavering support from the US, unlike Saudi Arabia whose human rights track record still manages to drag its activities under a close scanner. Thus, the Emirati nuclear programme is bound to be viewed with less suspicion than those of Saudi or Iran, especially since it has addressed and conformed to international safeguards. The increasing dominance of the UAE shows that the US has far more faith in Abu Dhabi than in Riyadh, which has been most apparent in yesterday’s peace deal with Israel that the American President has hailed as historic and is fielding as one of his biggest foreign policy wins.

HUGE breakthrough today! Historic Peace Agreement between our two GREAT friends, Israel and the United Arab Emirates!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 13, 2020

If we are to keep the environment aside for a minute, it can be argued that nuclear power is a crucial step in the Gulf states’ post-hydrocarbon development, especially after the pandemic. However, the geopolitical realities of the region, which seem to be shifting and polarizing in unpredictable ways, must be kept in mind by foreign investors and collaborators since the region is just steps away from becoming a breeding ground for nuclear warfare. It is imperative that the IAEA be allowed full and frequent access to facilities being developed in the Gulf and for the monarchies to, for a change, provide transparency to the international community.