With Cyclone Amphan destroying over 5,000 houses and killing 72 people in West Bengal alone, there have been several appeals from left-leaning intellectuals and civil society to declare the calamity as a ‘national disaster’. Many have been quick to call out Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his ruling party for ignoring the plight of Bengal due to political differences with the state government and have heavily criticized national news media houses for their lacklustre reporting on the disaster. However, while such criticism warrants investigation, there are several deep-rooted systematic factors that impede the Centre from taking timely action and providing financial support to states in the face of natural disasters, despite intent.

Firstly, there are three main steps of disaster management–mitigation, relief, and reconstruction. The Disaster Management Act, 2005 (DMA), which guides the country’s planning response, requires that plans for all-rounded disaster management be formulated at the district, state, and national levels, with corresponding funds. This means that, at any given point, six plans and six funds are required for disaster management at various levels. But, apart from the National Disaster Relief Fund (NDRF) and State Disaster Relief Funds (SDRF), other corresponding funds seem to be missing, especially for reconstruction.

At the same time, the DMA does not have any definition of what constitutes a ‘national’ disaster or calamity, and neither does it have clear demarcations for the classification of disasters as local, state, or national disasters. These clarifications have been made to a certain extent in the 2016 National Disaster Management Plan (NDMP), which categorizes disasters into three levels with an outlined scope of which authority is liable to provide capabilities and resources in case of a calamity. The levels have been defined as L1 (district), L2 (state), and L3 (national), based on the “vulnerability of disaster-affected area, and the capacity of the authorities to deal with the situation”.

In the past, there have been demands from states to declare natural disasters as ‘national disasters’–such as 2014’s Cyclone Hudhud in Andhra Pradesh, the Assamese floods of 2015, and Kerala’s 2018 floods–but all of these calamities were classified as being of “severe nature” and not large scale or catastrophic events that would demand action as per category L3. The coronavirus pandemic, which is biological in nature and has transcended state boundaries, is perhaps the first disaster to be classified as ‘national’. On the other hand, neither the ongoing locust swarm in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, nor the forest fires of Uttarakhand have been deemed as emergencies or crises as yet.

That being said, since disaster management is considered a state subject under the NDMP, the primary responsibility for the same lies with state governments, with the Centre contributing logistical and financial support only during ‘catastrophic’ disasters and on request by state authorities. This is why disaster management experts believe that the use of the phrase ‘national disaster’ by politicians and citizens alike is highly inconsistent with institutional realities.

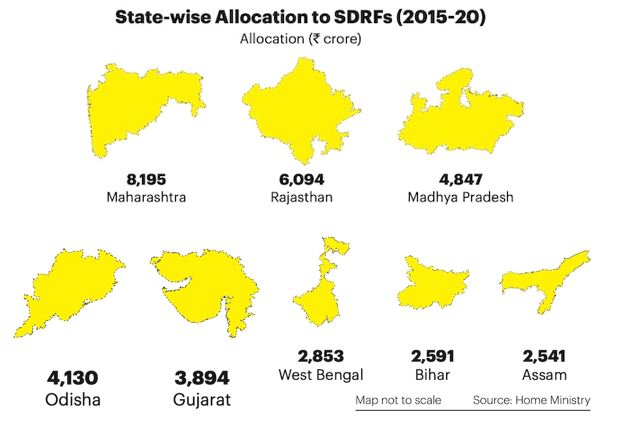

Further, there exists a severe lack of sufficient financial leeway as per the norms of the NDRF and SDRF, which restrain the Centre from providing financial assistance to calamity-prone states during natural disasters. The current mechanism of SDRF allocation is decided by the Finance Commission, where contributions are made by the Centre and states in a 75:25 ratio (in hilly areas, the Centre contributes 90%). And these fixed allocations disbursed from the NDRF to respective SDRFs are based on factors like state disaster expenditure, area, and population rather than considering the vulnerability of particular states to natural disasters. For example, in the total budget of INR 61,220 crore for the period of 2015-20, Maharashtra received the largest share of SDRF allocation, while Odisha, which has long been identified as the most vulnerable state, received only half that amount. West Bengal was also far down on this priority list.

More importantly, NDRF and SDRF funds are focused mainly on providing immediate relief in case of disasters and do not account for the massive rehabilitation and reconstruction costs borne by states to recover lost infrastructure and natural resources. While the Union Home Secretary in 2019 said that India had suffered losses to the tune of $80 billion due to natural disasters over the past two decades, the Centre only released an additional INR 7,000 crore and INR 10,000 crore to the NDRF and SDRF respectively for the year. To put numbers in perspective, 2019’s Cyclone Fani led to losses of nearly INR 12,000 crore in Odisha alone.

This fixed SDRF allocation system also disallows any flexibility for funds to be disbursed based on predictions by the meteorological department and is the primary reason why Central responses are always delayed and are discussed only after the disaster hits. For example, after 2018 Kerala floods, the state government requested a relief package of INR 21,000 crore for reconstruction but was only provided INR 3,048 crore from the Centre. When the state was afflicted with floods again in 2019, the Centre refused to release extra funds, citing non-expenditure of previous funds as the reason. However, a Kerala state government official pointed out that NDRF funds are highly limited in their scope of usage and the fixed-rate system is inconsistent with ground realities of expenditure. “For instance, the allocation is as little as Rs 1 lakh for a km of road, whereas the actual cost is around Rs 1 crore per km. Similarly, a fully damaged house is provided Rs 95,100, which is far from adequate. It is not enough for reconstruction at a scale required for a natural disaster,” they said.

Also, the borrowing capacity of states is limited under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003, so if the state does not have adequate resources for mitigation and restoration, these matters are dealt with extremely slowly. Responding to the massive infrastructural losses caused by Cyclone Amphan, NDRF Chief SN Pradhan said that the only way to reduce property damage and save lives is through the creation of disaster-resilient infrastructure, especially in coastal belts. However, just the cost of basic post-disaster rehabilitation borne by vulnerable states year after year leaves them with little financial support to undertake such large-scale and expensive infrastructure projects. For Odisha, this has resulted in a constant cycle of impoverishment and a severe migrant crisis, despite the state having arguably the most efficient disaster response system in the country.

The paradoxical nature of a decentralized disaster management system existing in tandem with a centralized funding system often drives affected states to source funding from the public on a case-by-case basis to their respective Chief Minister Relief Funds (CMRF) and the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund (PMNRF), which are public charitable trusts. While CMRFs usually raise money based on specific causes and campaigns, funds from the PMNRF are primarily used to offer relief to the families of those that have died in natural calamities or due to accidents and riots.

India also receives funds from international agencies like the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank during calamities and disasters of severe nature. Both organizations have also extended support towards the country’s fight against the coronavirus. In the past, states have been able to raise international funds directly in the past–such as the ADB and World Bank’s joint pool of around $900 million in three phases after the 2001 Gujarat earthquake. It is also worth noting that while India’s disaster funding systems are beset by such inadequacies and failures, the country is a ready provider of international aid for emergency disasters, especially to its neighbours and countries in Southeast Asia afflicted by similar natural calamities. Yet, the Modi government has prevented states from receiving foreign funding in the recent past.

Nevertheless, such mismanagement is not unique to the incumbent government. Prior to the Modi era, as per a Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) report in 2015, the National Disaster Management Authority of the country had no information about the progress of disaster management work carried out in states for the past 7 years. Simultaneously, it was unable to implement various planned projects for preparedness and mitigation, with these efforts being abandoned midway or sent for redesigning due to poor planning. The report also revealed that the authority had been functioning without its core expert advisory committee from 2012-2015. Such laid-back attitudes towards natural disaster mitigation and climate change threats across governments have further exacerbated the plight of already vulnerable states.

Therefore, while it is important to discuss the political motivations behind the Modi government’s neglect towards Bengal, it is equally imperative to look at the inherent flaws in the country’s funding system for disaster management that impede efforts despite intent. Odisha and West Bengal have been lauded internationally for preempting the disaster and evacuating as many people as they could, but are now being faced with the gargantuan challenge of rehabilitation and restoration.

There is an urgent need for robust changes that account for the realities of Indian states’ predispositions to varying natural calamities, especially in the face of climate change. The system should not be dependent on debts and donations and should rather focus on higher allocations to SDRFs, and flexible fund use. There must also be a shift towards exploring newer ways of international collaboration for funding, urban planning strategies, and natural resource management. Else, in the wake of the pandemic and consequent plans for massive industrialization across the country, even wealthier states may not be able to survive impending natural disasters.

Image Source: Free Press Journal/PTI