As the coronavirus ravages Iran, with both ordinary civilians and high-ranking government officials falling prey to this indiscriminate outbreak, attention has turned to the complicity of the United States in Iran's woes.

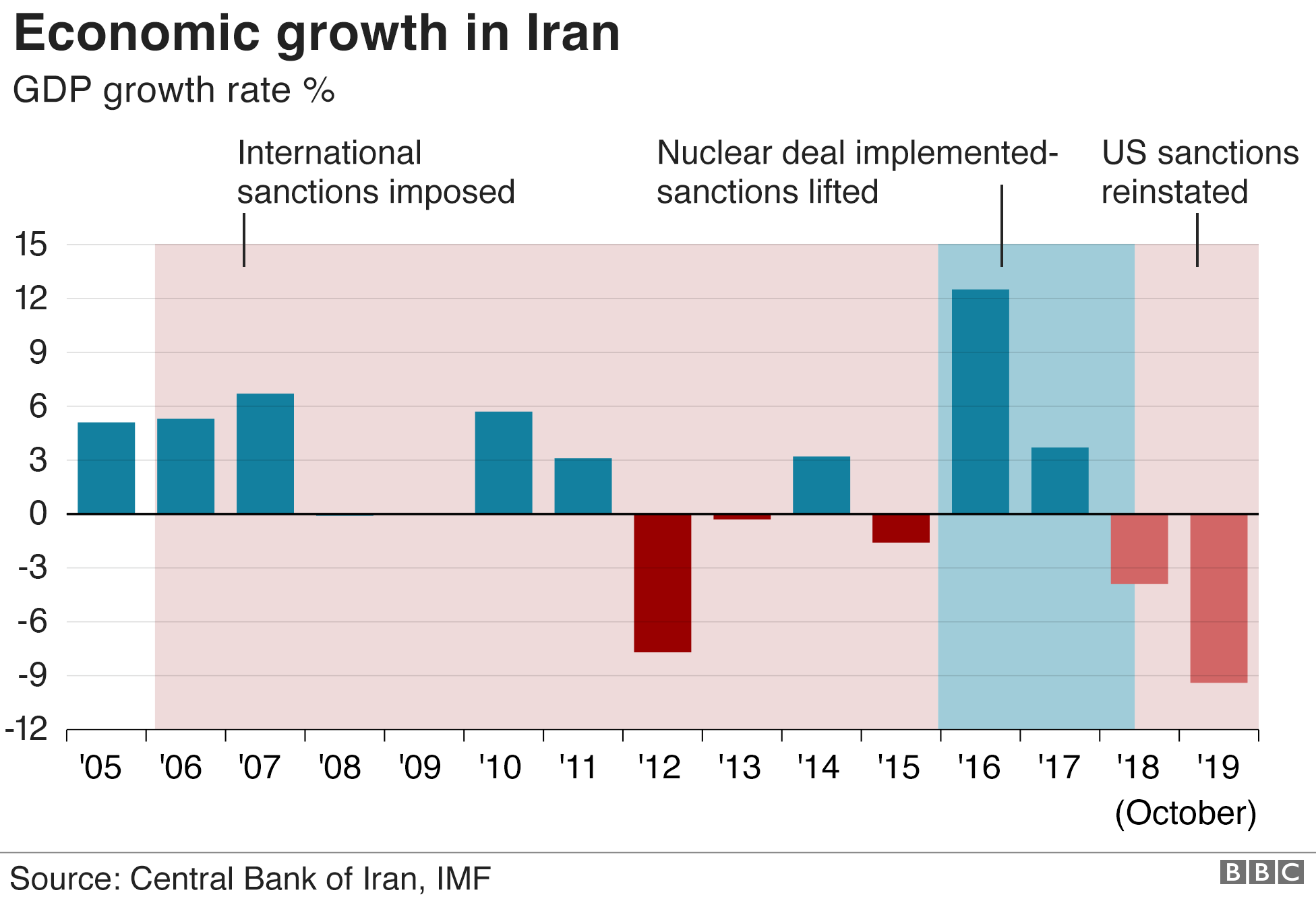

US sanctions caused Iran's economy to contract by roughly 9.5% in 2019. After signing the 2015 nuclear deal, world powers lifted sanctions on Iran, leading to an “economic growth spurt” and “recovery” in Iran, with 12.3% GDP growth in 2016. However, after US President Donald Trump pulled out of the deal and reimposed sanctions on Iran, much of this economic progress was undone, with Iran slipping back into the deep recesses of a crumbling currency, spiraling prices, and increasing unemployment. Trump hopes that the intensification of sanctions through a ‘maximum pressure’ strategy will force Iran to renegotiate the terms of the nuclear deal and accede to American demands.

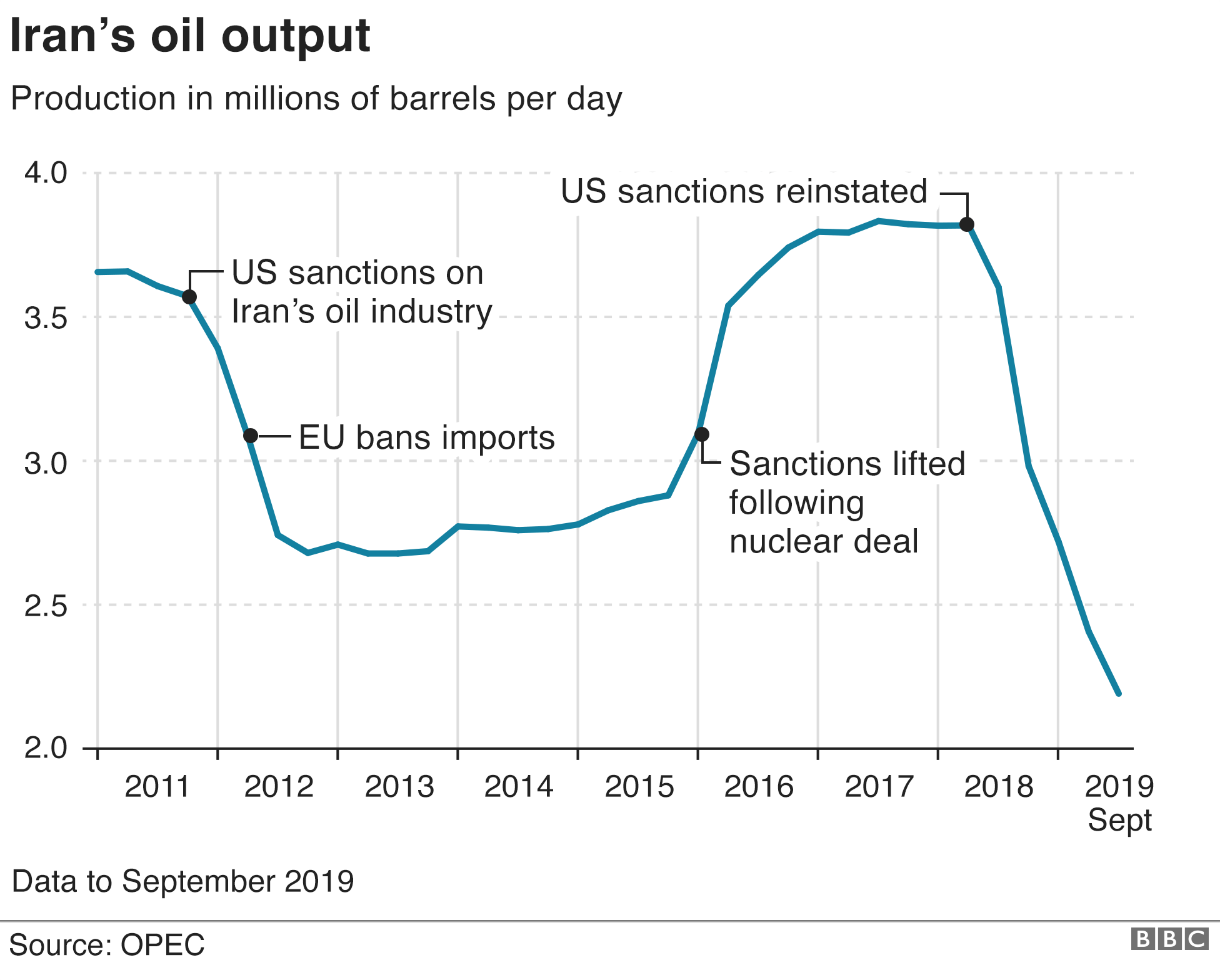

US sanctions target Iran's energy, shipping, banking, and financial sectors, causing foreign investment and oil exports to plummet. Furthermore, the sanctions are not only primary, prohibiting US companies from trading with Iran, but also secondary, extending to foreign firms and countries. Trump admits that his goal is to “bring Iran's oil exports to zero, denying the regime its principal source of revenue”.

Inflation is soaring, with food and beverage costs up by 61% and petrol costs by roughly 50%. Protestors took to the streets to voice their discontent against the Iranian regime, leaving over 208 dead, but the true culprit lies thousands of miles away on Pennsylvania Avenue, carelessly tweeting away into the depths of the night.

Iran’s plight has only been magnified with the onset of CoViD-19, with citizens unsuccessfully scrambling to find masks, gloves, and medicine in a country that appears totally bereft of a contingency plan for this global pandemic. Following an exponential rise in the number of cases, the demand for “respiratory masks and contamination suits, symptom relief medication, and immunity-boosting vitamins, as well as disinfectants, detergents, and related hygiene equipment” has reached unprecedented levels.

Although Iran does have extensive domestic manufacturing infrastructure, pharmacies and shops are “running low”, importers are “struggling to get their hands on new inventory and factories”, and factories are unable to keep up with surging demand. Iranian producers of medicine, disinfectants, and protective clothing are heavily-dependent on imported “ingredients and materials”. Iranian medical professionals report an inability to secure respiratory masks, surgical gowns, ventilators, and antiviral medication.

Given the primary and secondary sanctions by the US, many airlines and international shipping companies are no longer operating in Iran. The World Health Organization says that its attempts to deliver coronavirus testing kits to Iran have been delayed “due to flight restrictions”. Hence, US sanctions have severely constrained Iran’s ability to receive medical goods, raw materials, or humanitarian assistance. Consequently, its ability to contain the coronavirus epidemic has been severely impeded.

Humanitarian items–such as food, medicine, and medical devices–are technically exempt from sanctions, but the Trump administration used counterterrorism laws to “severely restrict” this form of trade. Multiple public and private Iranian banks are designated as terrorist entities, which precludes them from paying for humanitarian goods.

The vindictive and spiteful attitude of the US was also on display in its reaction to the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) October 2018 ruling, in which it ordered the US to “remove any impediments” to the importation of “medicine, food, and civil aviation products”. This included impediments related to the payment for these products. The ruling relied on the 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations and Consular Rights. Article 7 of the treaty states that neither nation will place monetary restrictions on each other to ensure the “availability of foreign exchange for payments for goods and services essential to the health and welfare of its people”. However, following the ICJ's ruling, the US withdrew from the treaty, essentially removing exemptions on food and medicine.

The debilitating impact of US sanctions on Iran’s ability to avert and now contain a public health emergency can be argued to be intentional. This is corroborated by the fact that the US, in fact, has a long, storied, and gruesome history of callously imposing harsh sanctions with little regard for their societal repercussions.

In 1962, the US implemented an embargo on all exports except food and humanitarian supplies to Cuba. Yet, a 1997 report by the American Association for World Health (AAWH) said that the embargo nonetheless contributed to “malnutrition [...], poor water quality, lack of access to medicines and medicinal supplies, and limited the exchange of medical and scientific information due to travel restrictions and currency regulations”. Moreover, the report says that although exceptions were technically made for certain goods, there was still a ‘de facto’ embargo on medicinal supplies.

From 1962-1992, medicines were allowed to be exported for "humanitarian" reasons. However, in 1992, the Cuban Democracy Act (CDA) banned foreign-based subsidiaries of US companies from trading with Cuba, and US citizens from traveling or sending family remittances to Cuba. After the passage of the CDA, access to medicine became even more difficult as every export of medicine required the certification of the president through 'on-site' inspections. Similar to Trump’s ongoing strategy with Iran, the act was designed to create a “democratic opening” by “wreak[ing] havoc on [the] island”. Moreover, this approach continues till date, with Trump intensifying the “economic, commercial, and financial embargo” against Cuba.

The US is also one of several countries to issue sanctions against Venezuela. The first of these sanctions came in December 2014 under the previous President Barack Obama through the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act, which places individual sanctions against specific people “deemed to be aiding the regime”, such as government and military officials.

Under President Trump, individual sanctions extended to sectoral sanctions by prohibiting US citizens from purchasing Venezuelan government debt. The Trump administration also placed sanctions on the Central Bank of Venezuela, the state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PdVSA), and Minerven, the state-operated gold mining company. In August 2019, Trump enforced a “total economic embargo” against Venezuela, minus humanitarian aid. Additionally, he empowered the Treasury Department to levy secondary sanctions against foreign and domestic entities doing business with the Maduro regime.

The US is hopeful that these sanctions will lead to regime change, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo calling for a “negotiated transition to democracy” and Donald Trump recognizing opposition leader and National Assembly President Juan Guaidó as the legitimate interim president of Venezuela.

The United Nations' human rights chief Michelle Bachelet said she was “deeply worried" the US' 'unilateral sanctions' will "severe[ly] impact on the human rights of the people of Venezuela”. One-third of Venezuelans struggle to meet minimum nutrition requirements. Studies show that sanctions have “reduced the public’s caloric intake, increased disease and mortality”.

Government mismanagement is largely responsible for hyperinflation, falling wages, rising prices, and shortages. Additionally, President Nicolás Maduro himself cut off foreign aid from the US, Canada, and the EU, saying their aid was a violation of Venezuela's sovereignty. However, his volatility is largely in response to the sanctions.

The US government’s willingness to use Venezuelan citizens as pawns in a larger strategy to achieve regime change is both opportunistic and manipulative. As Bashar al-Assad has shown in Syria over the past decade, an autocratic despot like Maduro is harder to remove than the US might believe, particularly when he can count on the enduring support of Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, and Hassan Rouhani.

North Korea, too, is reeling from the impact of US sanctions. After meeting with supreme leader Kim Jong-Un in Hanoi in February 2019, Trump said the talks broke down over sanctions, saying, “[North Korea] wanted the sanctions lifted in their entirety, and we couldn't do that.” The US is unwilling to relent until North Korea stops testing nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles. While there is limited data on North Korea, due to severe restrictions on information placed by the administration, the Seoul-based Bank of Korea estimated that North Korea underwent its biggest contraction in two decades in 2017, with its real annual GDP falling by 3.5% and its exports by 37.2%.

A 2018 UNICEF report details that 200,000 North Korean children suffer from acute malnutrition, and that sanctions put 60,000 of them at risk of starvation due to the "disruption in the availability of humanitarian supplies". While US sanctions exclude humanitarian aid, they nevertheless delay or “outright block” humanitarian shipments to North Korea. One NGO reported that it took over a year to ship 16 boxes of beans to the crisis-torn country. The sanctions also severely limit the transport of metal goods, which significantly disrupts the shipment of medical supplies. For example, a shipment of reproductive health kits was delayed as it contained aluminum steam sterilizers, which are the most vital element of the kit.

Bans on textile exports severely curtail female employment, and sanctions on the country's fishing, garment, and coal industries strip tens of thousands of North Koreans of their livelihood. The threat of secondary sanctions essentially forces US allies to fall in line, resulting in global sanctions against North Korea. For example, South Korea closed a joint factory complex that employed more than 50,000 North Koreans. And this past week, China's ambassador to the UN, Zhang Jun, warned that North Korea is “suffering negatively” from the coronavirus and urged the US and others to lift sanctions on the embattled nation.

These unforgiving measures have drawn the ire of multiple countries around the world. In fact, the term ‘economic terrorism’ has become somewhat of a catchphrase amongst the international community.

In November 2019, during the 74th session of the United Nations General Assembly, Belarus characterized sanctions against Cuba as “economic terrorism”. These sentiments were echoed by Nicaragua, Myanmar, Zimbabwe, Vietnam, China, Grenada, Tunisia, Azerbaijan, Singapore, Uganda, Russia, India, Mexico, Philippines, Algeria, Syria, Laos, Myanmar, Kenya, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Gabon, Angola, Nicaragua, Belize, Indonesia, North Korea, Jamaica, South Africa, and Sudan.

In 2019, Iranian Foreign Minister Javed Zarif also accused the US of “economic terrorism” and “cutting off access to cancer drugs”.

Grateful to @WHO & friendly nations for solidarity in fighting #COVID19—in face of US #EconomicTerrorism, which has endangered Iranian patients.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) March 2, 2020

Urgent need in Iran for:

- N95 Face & 3-Layer Masks

- Ventilators

- Surgical Gowns

- Coronavirus Test Kits

- PPF

- Face/Body Shields

In February 2020, The Venezuelan government filed a request with the International Criminal Court seeking an investigation into American officials for "crimes against humanity" for their sanctions, with the country's Foreign Minister, Jorge Arreaza, calling the sanctions a "weapon of mass destruction" against the Venezuelan people.

In 2018, Kim Jong-un lauded his citizens for handling the “difficult living conditions caused by life-threatening sanctions and blockade”. In early February 2019, prior to the Hanoi conference, a memo by North Korea’s ambassador to the UN, Kim Song, described how the “barbaric and inhuman” sanctions were to blame for a ‘food crisis’ in the country.

Given the supposed illegitimacy of Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea’s regimes, it is easy to dismiss their concerns as oppressive regimes shrouding themselves from blame. However, one suspects that these same genuine concerns and valid criticisms would be given more credence if they came from a democratically elected leader. These countries’ governments have no doubt contributed greatly to their own citizens’ misery, but US sanctions have hammered the indelible final nail to their coffins.

Regardless of the culpability of these administrations, it is the civilians who get caught in the crosshairs. Civilians are held hostage to the machinations of great power politics as the US coerces their countries to accede to its demands through the threat of starvation, bankruptcy, lawlessness, unemployment, disease, and, ultimately, death.

There is insurmountable evidence that the US has knowingly let innocent civilians die as part of its ‘maximum pressure’ campaigns in its pursuit of submitting world powers to its will and expanding its sphere of influence. While it may not have directly killed them, that the US is both eager and willing to use the lives of helpless people as political currency is indicative of the eugenicist and genocidal underpinnings of its sanctions.

There is perhaps no more apt illustration of this than former UN ambassador and US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright's '60 Minutes' interview in 1996. Her exchange with correspondent Lesley Stahl went as follows:

Lesley Stahl: “We have heard that half a million children have died. I mean, that's more children than died in Hiroshima. And, you know, is the price worth it?

Madeleine Albright: “I think this is a very hard choice, but the price–we think the price is worth it.”