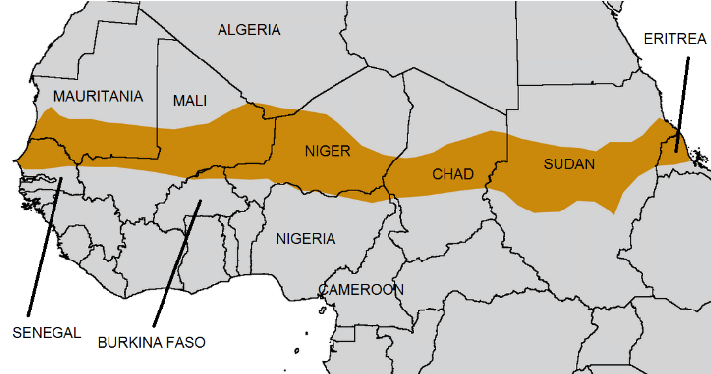

There is a strip of land just below the Sahara Desert, that stretches across the entire African continent, where the stakes for rain and peace are high. It is known as the Sahel, and it comprises portions of 10 African nations, from northern Senegal on the Atlantic coast, through parts of Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, and Sudan, to Eritrea on the Red Sea coast.

The semi-arid region has been characterized by severe climate risks, crippling food insecurity, and in recent years, metastasizing violence in three countries—Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger—which has and continues to endanger the lives of millions. This ‘fireball of conflict’, which is swiftly engulfing most of the Central Sahel region, is further made complicated by the presence of a multitude of actors—from non-state armed groups, to national and international forces, to local militia.

The security crisis has its roots in the January 2012 uprising in Mali, where an alliance of separatist Tuareg rebels and jihadist armed groups launched a rebellion in the north against the central government. Islamic militants quickly took over strategic northern towns, and the insecurity and violence that followed displaced nearly 375,000 people over the next 12 months. The situation prompted a military intervention by former colonial power France in January 2013, which aimed to halt the advance of the Tuaregs and allied jihadist groups towards the nation’s capital Bamako, and prevent the total collapse of the Malian state. Though the mission, known as ‘Operation Serval,’ was successful in dislodging militants, local groups linked to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) have since regrouped, and continue to exploit local conflicts, poverty, and religious and ethnic divisions to secure safe havens and win new recruits. Owing to a combination of porous national borders, an abundance of non-state armed groups, and weak state authority, insurgencies and intercommunal violence have now spread not only into central Mali, but also into the wider region.

Burkina Faso and Niger have also seen a surge in hostilities in recent months. Burkina Faso, which was previously hailed as a success story of religious diversity, inclusion, tolerance and social cohesion in West Africa, is now in the grips of a violent existential crisis, perpetuated by extremist groups. Following the ousting of President Blaise Compaoré in 2014 after 27 years of his rule, the country failed to consolidate power and created a security vacuum, which has since been exploited by jihadists. Like in Mali, attacks by militant groups are also fanning the flames of intercommunal tensions, as certain groups are accused of joining or harboring the insurgents. Attacks against the Fulani communities in both Mali and Burkina Faso, for instance, have increased due to such hateful rhetoric. As a result, there has also been a proliferation of community militias. Violent clashes between these groups have killed scores of people, forced thousands out of their homes, and pushed entire communities to the brink of starvation. According to the UN, as of April 2020, more than 830,000 people are displaced internally in Burkina Faso and 2.2 million are in need of humanitarian assistance.

In Niger, the 2017 killing of Nigerien troops and US Special Forces near the border between Mali and Niger brought international attention to a long-neglected region that has been plagued by security threats, endemic poverty, hunger, malnutrition, and disease. In 2019, Niger ranked last on the UN’s Human Development Index, and increasing insecurity along its western and southeastern borders has only moved the situation from bad to worse. Armed groups with supposed links to the Islamic State have repeatedly targeted Nigerien security forces, and the resulting insecurity has internally displaced more than 97,000 people. Sexual violence, kidnappings for ransom, mass killings, murders, looting, and destruction of houses of civilians by armed groups is rampant. Niger also regularly absorbs refugees from Mali and Nigeria. Almost 250,000 people who fled their homes due to the Boko Haram now live in makeshift camps in Niger’s Diffa region in the southeast near the Nigerian border. Clashes in Niger have also led to thousands fleeing to neighboring Mali—a country already riddled with conflict—thereby pushing civilians into a constant cycle of misery.

According to the UN, terrorist attacks have increased fivefold in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger in recent years, with more than 4,000 deaths reported in 2019 in the border areas between the three countries, as compared to the 770 deaths reported three years prior. The African Centre for Strategic Studies has reported that violent activity from militant groups in the Sahel has doubled every year since 2015. Terrorism, organized crime, and inter-communal violence is spreading in areas where the State’s presence is weak, and attacks against civilians have been on the rise, both in number, and frequency. Civilian deaths in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have increased fourfold since 2018. More than 1,000 civilians had lost their lives in the first four months of this year alone.

The international community has intervened, but has struggled to halt the violence in the region or address the root causes of the rapidly deteriorating situation. In 2013, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) established a peacekeeping mission in Mali, called MINUSMA (UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali), which was followed by France launching its counterterrorism ‘Operation Barkhane’ in 2014 (which replaced ‘Operation Serval’ and expanded its reach regionally). The Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram has also been present in the Lake Chad region since 2016, and the UN-AU-EU-backed G5 Sahel Joint Force came into force in 2017. Apart from these, there are also a number of United States (US), German, Belgian, British and Italian soldiers on the ground, both within MINUSMA and in the framework of bilateral agreements with countries of the Sahel (where some of these nations have military bases).

However, funding shortfalls, conflicting and insufficient mandates, and coordination disputes have led to the multilateral forces being unable to stem the tide of violence. At its annual summit in Addis Ababa earlier this year, the African Union (AU) spoke of possibly deploying 3,000 troops in the Sahel for 6 months, to work with the MNJTF and G5 Joint Force to address the terrorist threat in the region. However, the exact modalities of such an intervention are yet to be worked out, especially with regards to financing and troop contributions, which would affect the composition of the force. Furthermore, there are also looming concerns about potentially overcrowding the security space in the Sahel, which is already problematic.

The frustrations over the troops' failure to curb violence and insecurity have also been compounded by allegations of horrific human rights abuses by these troops, including unlawful extrajudicial killings during military operations, sexual and gender-based violence, and maiming. As terror attacks intensify, the crackdown by state and international forces is that much more brutal, and thousands of innocent civilians are getting caught in the crossfire. Aid organizations operating in these areas have emphasized that the military response in the region is “part of the problem”, asserting that social and economic challenges will also need to be addressed in order to carve a path towards sustainable peace and stability.

The toxic mix of escalating armed conflict, displacement, hunger, and widespread poverty in the Sahel is only exacerbated by the acute impacts of climate change. Erratic rainfall is common, and wet seasons are shrinking. Almost 80% of Sahel’s farmland is degraded, and the temperatures are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average. Longer and more frequent droughts are further undermining food production, along with risking people’s lives and livelihoods. 5.5 million people—out of a total of 12 million—are on the brink of facing emergency levels of food insecurity. 7.5 million people in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger are in need of humanitarian assistance and protection, marking a rise of 1.4 million people in one year, and more than 1.2 million people have been uprooted from their homes.

The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic is going to push this already overwhelming crisis to its tipping point. Last month, the UN Migration Agency (IOM) sounded the alarm about the unprecedented levels of humanitarian need across the region. Apart from the internally displaced and refugees, travel restrictions have left over 20,000 migrants stranded at borders, and another 2,000 waiting in transit centers. Since they have limited access to healthcare facilities, the lack of testing or treatment of COVID-19 cases among these groups could lead to devastating outcomes for host populations.

Sustained international attention and effort is needed to address this tragedy unfolding right before our eyes. While the security implications of the situation has prompted foreign intervention in the region, it has to be backed up by continuous and strong support for local and regional development, humanitarian, and peacebuilding efforts, that address the urgent needs of civilians. For instance, The AU Peace Fund has been set up to serve exactly this purpose, and countries should commit to contribute to the endowment, which currently stands at $150 million, to prioritize activities such as mediation and preventative diplomacy. With millions of lives on the line, inaction is not an option.

Image Source: NRC