With today’s slight withdrawal of troops from the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between India and China in eastern Ladakh, it seems that the 6 June meeting between the two nations’ general officers has led to a partial de-escalation of the border conflict. However, the increased presence of Chinese troops at the frontier–which Shekhar Gupta described as ‘predictable’ after the unilateral abrogation of Article 370 last year–has definitely shaken New Delhi, who must now strengthen avenues to maintain its position in the region, especially in the neighbourhood and in the country’s strategic waters.

In the same tune, it appears that last week’s virtual bilateral summit between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Australian counterpart Scott Morrison has brought back to surface New Delhi’s attempts at strategic hedging in the Indo-Pacific, specifically the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). And while the Indian Ministry of External Affairs denied any mention of China at the summit, it is undeniable that the signing of new strategic and maritime security agreements between the two countries has come against the backdrop of Beijing’s increasing presence in the region.

In the recent past, China has adopted a strong and relatively unchecked combination of political support, hard military tactics, and high economic patronage with nations in South and Southeast Asia to gain its foothold in the regional waters. Thus far, India has been unable to match the Asian power in both economic and strategic support to the other countries involved–rather, it is highly dependent on medical diplomacy and its deep historical and societal ties to maintain its dwindling ‘big brother’ relationship with most of its neighbours.

China’s String of Pearls strategy, through which it has been spreading its naval power in the high seas with help of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), poses a major threat to regional stability in the Indo-Pacific. The power has been expanding its presence in the IOR as well as the central and western Pacific Ocean, claiming almost all of the South China Sea. Its claims are countered by Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, and the Philippines. This massive Chinese presence in the high seas, especially in the IOR, also poses a credible threat to India and Australia’s security interests in the seas of the region.

See also: Philippines Temporarily Backtracks From Decision to End Military Agreement With US

Since 2014, the Modi government has placed a special emphasis on an enhanced presence in the IOR to harness security at its coastlines and build a blue economy. In an Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA)-led effort, India aims to promote inclusive, sustainable, and smart employment opportunities for those involved in the IOR’s economic activities like aquaculture, fisheries, seafood farming, shipping, renewable energy, and blue carbon efforts, among others.

To achieve these goals, New Delhi has focused on prioritizing relations with the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), as well as actively pursuing its Maritime Capability Perspective Plan (MCPP). From a security perspective, the MCPP is a grand plan to bolster India’s regional maritime operational capabilities by introducing new submarines, warships, and aircraft. The aim is to increase naval capabilities by introducing 500 aircraft, 200 ships, and 24 attack submarines by 2027. Procurement delays and slow inductions have even prompted Modi to consider talks with Russia to collaborate on building the ships. But the process for this is still ongoing, and India’s enhancement in the seas is not just limited to this.

New Delhi is also focused on implementing robust efforts towards maritime diplomacy with Southeast Asia and IOR littoral states in the spirit of its Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) initiative to ensure expansive and effective partnerships with islands and countries in the region. However, for SAGAR to truly emerge as an alternative to the Chinese BRI would require India to provide competitive investment strategies to secure its regional interests and play great power politics in the ocean. Compared to China, though, India has a long way to go with respect to assisting its maritime partners in building security capabilities and infrastructure.

It is also worth noting that before 1991, conflicts in the IOR were almost wholly managed by the United Nations (UN) and international organizations as per the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). But the ambit of international law mechanisms dealing primarily with states was ill-equipped to deal with complex crime networks, pirates, and terrorist threats emerging from non-state actors in the Indian Ocean. This lack of legal frameworks to check the IOR also allowed China to increase its military presence and strategically align itself with smaller nations.

This gargantuan role played by Beijing in the IOR has heightened New Delhi’s need for strategic cooperation with other powers to work towards its national security interests in the region. Beijing has already rubbished the United States-Japan-Australia-India Quadrilateral Dialogue (Quad)–which was resurrected in 2017–as a “headline-grabbing idea” that is “doomed to fail”. And while the grouping is not technically an alliance, New Delhi must break away from the status quo so as not to weaken its strategic autonomy by being reliant on quadrilateral relations.

It is apparent that China considers growing Australian maritime involvement as a nuisance–in 2008, it raised a high objection to Canberra’s participation in the Malabar Exercise with India, Australia, and Japan. But with the AUSINDEX exercises established in 2015, New Delhi and Australia already demonstrated their re-emergence of maritime ties.

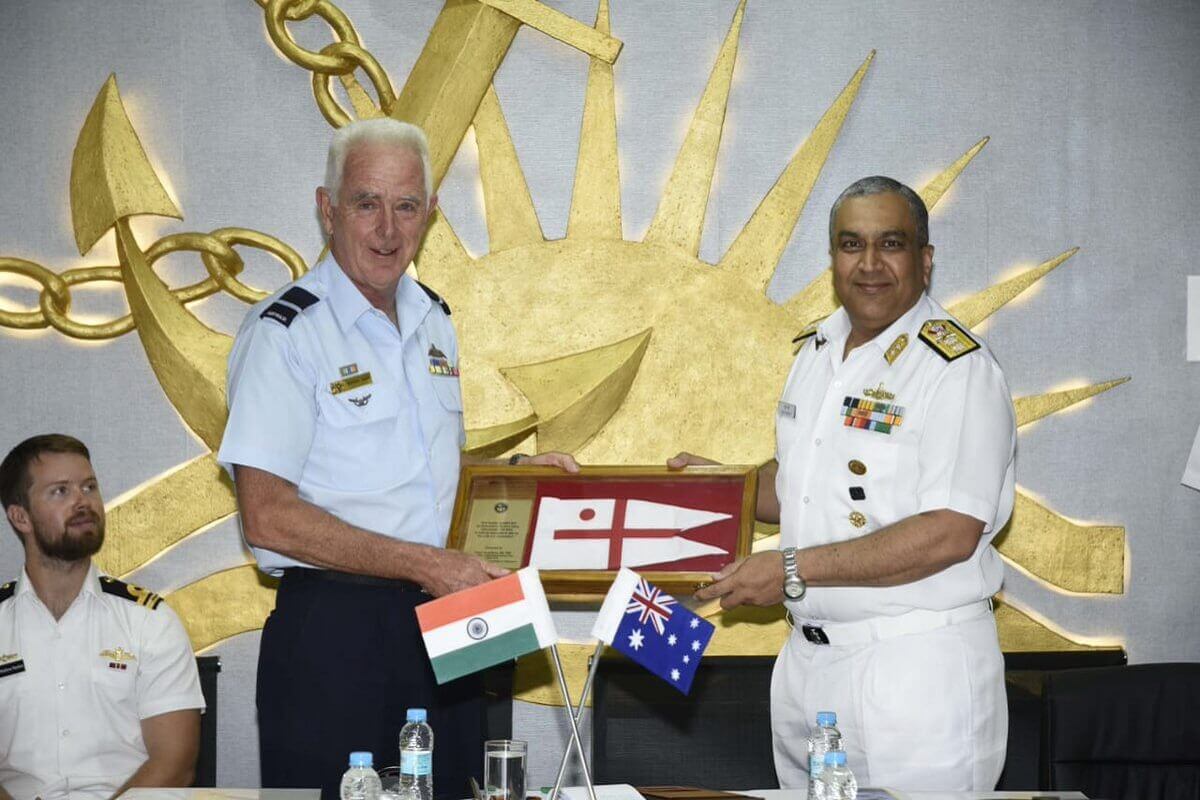

And with the signing of several important documents during their virtual summit on 4 June, Modi and Morrison have agreed to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership that includes a network sharing arrangement of cyber-enabled critical technology, cooperation on mining critical minerals (for which both have traditionally been dependent on China), water resources management, and a landmark Mutual Logistics Support Agreement (MLSA) that allows for the building of stronger links between civil maritime agencies and coastguards to develop deeper navy-to-navy engagement. In their Joint Declaration on a Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo- Pacific, the leaders reiterated their commitment to international law and “supporting a rules-based maritime order” to tackle non-traditional threats like piracy, terrorism, illegal human and animal trafficking, drug smuggling, unregulated fishing, and climate change among others. Further, they committed to working towards supporting regional architecture and the centrality of the ASEAN and related multilateral fora like the IORA, IONS, ARF, IOTC, IMO, and ADMM-Plus.

Therefore, while Australia is not a large enough power to help India quash Chinese interests in the IOR, a strengthened maritime relationship and the building of a secure bilateral structure in the region can deter unilateral action from single actors like Beijing and disallow them from disrupting regional stability in the Indo-Pacific. The MLSA would allow for both countries to access each others’ military bases and share equipment and intelligence. On an almost immediate basis, this would give India a massive strategic boost as it can now expand its presence and reach the Pacific across the Indonesian straits via the Cocos islands, which border some essential trade routes along the coastline. Under a deal with Kuala Lampur, Canberra also has access to an airbase at Butterworth which New Delhi may be able to leverage as well.

In the face of rising Chinese military presence in the region, several world powers have voiced their support for a free and open Indo-Pacific. Accordingly, China is growing wary of India building global alliances to deter further Chinese aggression and presence in the region. In an interview with Su Hao, founding director of China Foreign Affairs University’s Center for Strategic and Peace Studies, the CCP media outlet Global Times has already reported that by inking these deals with Morrison, Modi “may hope to shape more pressure toward China from the international community – in particular from the West.”

And while these new and enhanced cooperation deals with Australia will work towards these goals, Modi must also carefully manage his balancing act with Beijing considering the latter’s unwavering stance towards its territorial interests and the budding economy’s heavy reliance on cross-border trade. With the likelihood of a cold war between the US and China and with American President Donald Trump clearly stating his support for India in its ongoing border dispute with China, New Delhi must also be careful in how it hedges its relationships with the Quad, lest it foments the idea that India is breaking away from its culture of non-alignment.

It appears that India’s hedging strategy of building security links with regional powers while creating a modus vivendi with China is intensifying its security dilemma with its neighbour. Informal bilateral Modi-Xi summits and shared pleasantries based on historical and societal ties may not be enough anymore. As a country that is highly dependent on investment and trade from Beijing for its own economic growth, the key question remains as to what Modi plans to prioritize in his relationship with Beijing. The rather opaque domestic reportage of the recent border skirmish and downplaying of the diplomatic crisis with Nepal seems to indicate that Modi is reluctant to make any bold moves at the frontiers.

At the same time, as talks of extending an invite to Canberra for the next Malabar Exercise emerge, it is important that Modi find a way to ensure that his relationship with the Quad does not translate to one of alignment with the US, else it stands to face multiple security and economic threats from China.

Image Source: The Statesman