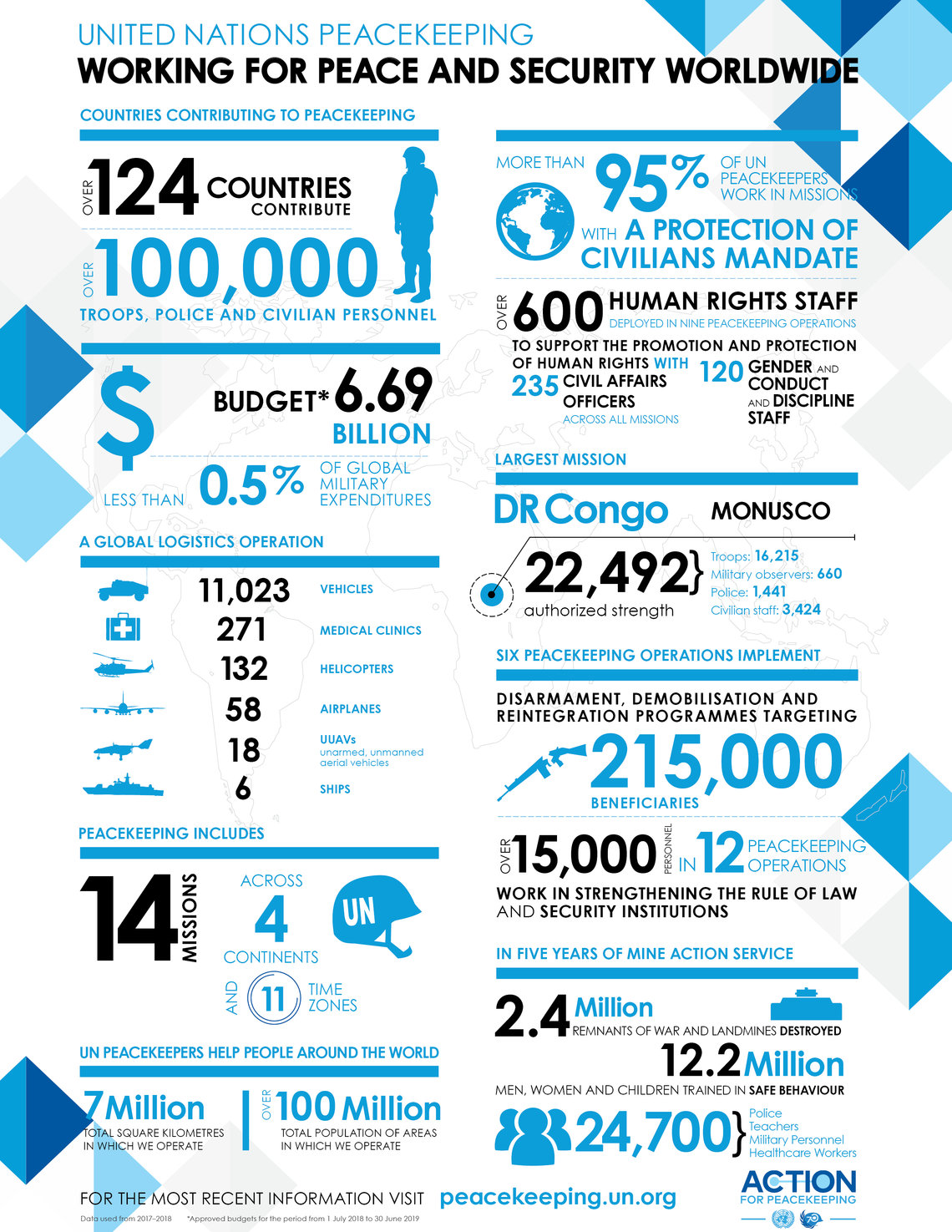

The coronavirus pandemic is perhaps the biggest test of global leadership, and along the way, it is highlighting the challenges facing the international community in coordinating crisis and disaster responses. Over the last month, United Nations peacekeeping missions–which are considered to be the organization’s most unique and dynamic instruments to support peace and stability in fragile contexts– have been in full crisis management mode to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among their 100,000 plus civilian, police and military personnel spread across 3 continents.

As these missions are forced to adapt to a new reality at a much higher pace than at any time before, it is important to be realistic about what they can achieve, and how this crisis could significantly alter peace operations in the months to come.

In response to the pandemic, missions are already assessing what activities are essential–and therefore need to be adapted–and which ones can be paused until the crisis is over. Five out of the 13 active peacekeeping missions–in South Sudan (UNMISS), Darfur (UNAMID), Central African Republic (MINUSCA), Mali (MINUSMA) and Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO)–have explicit protection of civilians (POC) mandates, which involve essential activities like patrols and convoy escorts, humanitarian assistance, force protection, protecting key infrastructure, and support to host state institutions and local authorities. Some missions have halted their quick impact projects (QIPs) for the time being and are diverting their resources and support to local and national bodies tasked with responding to the novel coronavirus.

Minimizing the risk of transmission from peacekeepers to local communities is a crucial consideration for missions. After having acknowledged their role in the 2010 Cholera outbreak in Haiti, and due to previous–and continued–criticism about peacekeepers’ spreading HIV/AIDS in certain regions, the UN is aware of the acute danger that these missions may pose to host populations.

Some have already adopted restrictive measures. For instance, in Lebanon, UNIFIL has quarantined a whole battalion that was recently rotated into the country. Similar measures have been adopted in the UN mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), where flights for UNMISS staff moving between different field locations within South Sudan have been limited to essential movements only.

While missions are adapting to this crisis as much as they can to prevent and contain the virus, the pandemic is bound to have long-term impacts on their ability to achieve their goals and objectives, which, in crisis-torn regions, is already very difficult. Most missions are characterized by vague and lofty mandates from the Security Council to address complex challenges in extremely difficult operational environments, all without sufficient guidance or funding. With mandates not reflecting the realities on the ground, and financial donors, troop-contributing countries (TCCs), and police-contributing countries (PCCs) hesitant to provide more resources, missions are ultimately rendered dangerous and counterproductive. Missions are already stretched too thin, and the global recession that is looming due to the coronavirus pandemic will make it even more difficult to obtain the required levels of funding as donors divert resources towards domestic responses.

Suspending rotations of peacekeepers, while a necessary step, may also produce some negative consequences. On April 7, the UN announced that it was suspending rotations of uniformed personnel at all 13 missions until June 30, 2020. This has severe implications for both host countries and their populations, and the missions and their personnel as they deal with understaffing or prolonged deployments. The latter could have an impact on the staff’s mental health, and missions will have to make tough decisions to balance taking care of their people and implementing their mandates.

With limited resources and fragile security situations already complicating response measures, it will also be challenging for understaffed missions to ensure a safe environment for health workers to operate in, further impeding mitigation efforts. This was a key challenge to contact tracing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) during the 2016-18 Ebola outbreak. Violence and kidnapping by the Uganda Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the presence of armed groups operating in the region meant that there was a constant threat to the lives of health workers, as they faced an average of three to four attacks per week. This significantly affected response teams’ ability to contain the virus, as the security situation made it difficult to access affected populations and for health workers to identify and follow up with contacts of known cases. As the number of follow-ups dropped, new Ebola patients continued to be identified, which meant that there was perhaps “considerable transmission” that was going undetected. These new cases could potentially have been prevented if there were safer working conditions for health workers.

Planning for a potential large-scale evacuation of workers also seems futile. These missions are massive–MONUSCO, for example, has more than 17,000 personnel on the ground–and it is unlikely that countries would accept several thousand evacuees. Moreover, if missions leave, they would leave humanitarian workers to fend for themselves in areas where they are dependent on assistance by international military forces. In the case of the Ebola outbreak in Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014, the deployment of militaries was key to convincing many NGOs to maintain or establish operations in affected countries. In volatile regions, peacekeeping forces may be essential to ensure the safety of humanitarian workers and to enable their access to hard-to-reach populations.

Peacekeepers can provide either direct support to medical responses or logistical support through mobilizing air assets, and transporting patients and medical equipment. However, insufficient training, a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and misinformation about this pandemic may lead to troops being unable to perform their duties. For example, peacekeepers could become wary of transporting infected patients, which could hurt response efforts. This was seen during the response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa as well, where some forces were criticized for refusing to transport infected patients, which hampered productive civil-military engagement. Similar risk aversion may take over host countries in dealing with the coronavirus too, as local populations could become more hostile towards the presence of foreigners on the ground. Host governments could also exert more pressure on missions and limit their movements under the guise of restrictive measures to contain COVID-19, which would adversely affect their operations.

While most places where peacekeeping operations are active are on the periphery of the pandemic, the speed and reach of COVID-19 make it inevitable that the virus will eventually severely impact their work. Going forward, missions will have to consider a multitude of complex and interlinked dynamics in their operational environments. However, they cannot do this alone. They will require the full support of the UN Security Council. Mandates will have to be revised to reflect the new realities, risks and challenges. Alhough domestic turmoil is likely to consume member states due to the devastating fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, their international obligations during such a crisis cannot take a backseat.

Image Source: United Nations Peacekeeping

List of Abbreviations:

COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019

DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo

MINUSCA: United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic

MINUSMA: United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali

MONUSCO: United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

PCC: Police Contributing Country

POC: Protection of Civilians

QIP: Quick Impact Project

TCC: Troop Contributing Country

UMISS: United Nations Mission in South Sudan

UN: United Nations

UNAMID: United Nations Mission in Darfur

UNIFIL: United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon