On Tuesday, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) released its 2021 World Press Freedom Index, and revealed a “dramatic deterioration” in citizens’ access to information and a commensurate rise in the hurdles placed before journalists. In fact, the report claimed that journalism, which RSF describes as “the best vaccine against the virus of disinformation”, is “totally blocked or seriously impeded” in 73 countries and “constrained” in 59 countries, which cumulatively represent 73% of the 180 countries studied.

RSF argues that the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has been used as a pandemic to restrict journalists’ access to information and their ability to conduct field reporting. In fact, it noted that several world leaders—including Venezuela’s (#148) Nicolás Maduro, Brazil’s (#111) Jair Bolsonaro, the United States’ (#44) Donald Trump, Kyrgyzstan’s (#79) Sadyr Japarov, Tanzania’s (#124) John Magufuli, and Madagascar’s (#57) Andry Rajoelina, to name but a few examples—have attempted to supplant the role of journalists by touting unproven and often dangerous treatments for COVID-19. Others, like Egypt’s (#166) Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi have outright banned anyone but the Ministry of Health from publishing statistics on the pandemic.

Overall, the report concluded that the situation of press freedom is very serious in 11.88% of the countries, difficult in 28.71% of countries, problematic in 32.67% of countries, fairly good in 19.80% of countries, and good in just 6.93% of countries.

Asia-Pacific

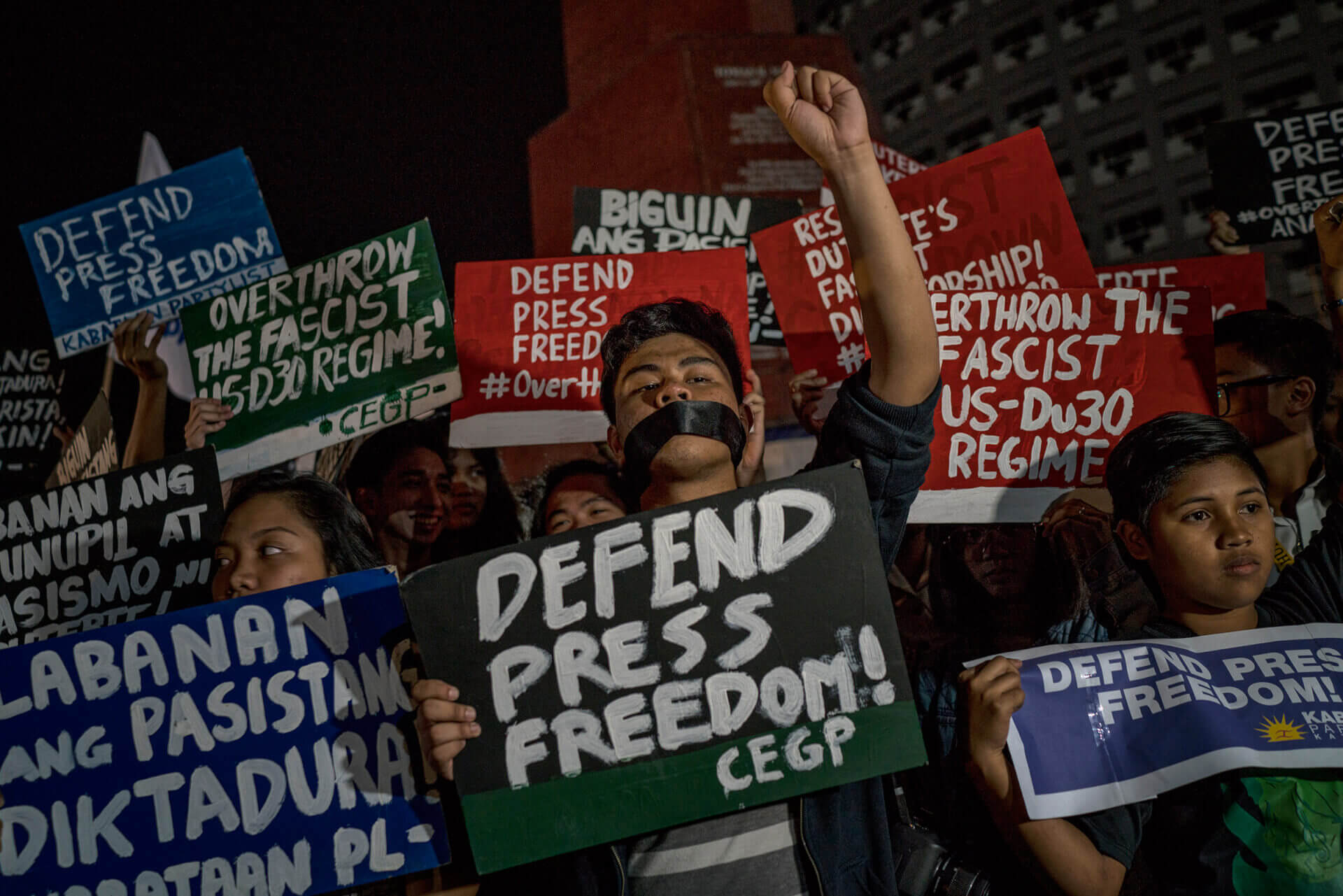

Aside from the “methods of totalitarian control of information” employed by the region’s “authoritarian regimes”, there is also a worrying but continued trend of “repressive legislation” and “suppression of dissent” by what the RSF describes as “dictatorial democracies”.

In India (#142), pro-government accounts are often used to spread propaganda and even hate against critics of the government, wherein journalists who speak up against the government are often declared to be “anti-national”, “anti-state”, or “pro-terrorist” by supporters of the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP). This often has real-world implications, where journalists are harassed and even physically attacked by BJP supporters, often with the help of the police. At the same time, many of these critics face arbitrary arrests on charges like “sedition” and “endangering national security”.

In Pakistan (#145), the military’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) uses chilling tactics like “judicial harassment, intimidation, abduction, and torture” to “silence” and intimidate critics of the military and government both within and outside the country’s borders.

Similar declines in press freedoms have also been reported in Bangladesh (#152), Sri Lanka (#127), and Nepal #106). Meanwhile, Afghanistan (#122) remains the world’s deadliest country for journalists, with six media workers killed in 2020 and four more since the turn of the new year.

China was ranked at 177 and RSF described the Asian giant as the world’s “undisputed specialist” in the “censorship virus”. For example, by passing the National Security Law on Hong Kong, it can now arrest any critics of Beijing under the guise of national security. This firm control over access to information is even more prevalent in the mainland, where the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which is overseen by President Xi Jinping, heavily controls information, spies on or censors citizens, and disseminated propaganda to steer national discourse.

North Korea ranks at 179, which is hardly a surprise, considering Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un’s continued iron grip on power in the country. It was recently revealed that state media in the country has left citizens in the dark over the development of COVID-19 vaccines, possibly due to the fact that it is entirely reliant on donations from other countries that could still take a while to arrive.

Although not as severe as in China or North Korea, press freedoms are also quite dismal in Thailand (#137), the Philippines (#138), Indonesia (#113), Cambodia (#144), Malaysia (#119), Myanmar (#140), and Singapore (#160), where criticism of the government is often punishable under conveniently created “anti-fake news” laws. The situation in Myanmar, in particular, is of particular concern, especially after the coup in February, which was followed by mass arrests of journalists.

There is, however, some cause for celebration with Bhutan (#65), Mongolia (#68), Timor-Leste (#71), New Zealand (#8), Australia #25), South Korea (#42), and Taiwan #43) who have all worked towards ensuring sufficient separation between the state and the media industry, even during the ongoing pandemic.

Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

In Syria (#173), the Assad regime has banned all information on the coronavirus throughout the pandemic, despite evidence of rising cases in neighbouring Iran (#174) and Lebanon (#107). Such actions have ultimately discouraged citizens from turning to the media at all. In Saudi Arabia (#170), even pro-government journalists reported a drop in readership and viewership, as the public increasingly began to get their information directly from government websites, since the two have become essentially indistinguishable anyways.

Like in a number of countries in the region, Iran has heavily censored information on the number of deaths from the coronavirus, so as to minimise criticism of the government’s handling of the pandemic. Although the government’s official death toll is around 80,000, independent studies reveal that the number could be well above 180,000.

Press freedom in four countries in North Africa—Egypt (#166), Morocco (#136), Algeria (#146), and Libya (#165)—was recorded as “bad” or “very bad”, even in the face of popular movements demanding greater freedom of expression and access to information since the Arab Spring at the start of the previous decade. The reason for this lowly ranking is attributed to “judicial harassment of journalists”, “arbitrary arrests”, “interminable provisional detention”, and “repeated trials”.

Given that many journalists cover protests in the region, they are often seen by government authorities as being one with the demonstrators or “inciting” rebellion, violence, riots, or “unauthorised demonstrations”, such as the protests in Iraq’s (#163) Kurdistan the Hirak movement in Algeria. This has been complemented by a rise in “hate speech” against the media, often by far-right politicians, such as in Tunisia (#73). Likewise, in Jordan (#129), journalists were either arrested for or banned from releasing information on unemployment and protests by teachers.

Likewise, in Egypt, authorities are legally permitted to censor online media and jail journalists for spreading what the government regards as “fake news”, and put out a notice saying that state-owned news agency Sana was the only provider of “valid information”.

RSF contends that this has left journalists in the region having to choose between two equally undesirable options of ‘self-censorship’ or propaganda.

North America

The US became a hotbed for misinformation during the pandemic, when several alternative news outlets spread false information about the virus and treatments for it. In fact, many of these wild conspiracy theories originated from the White House, with President Donald Trump spouting one wild lie or claim after another.

Furthermore, there was also a troubling increase in the number of attacks on media workers in 2020, with many of these acts of aggression perpetrated by law enforcement officials during the Black Lives Matter protests.

Furthermore, Twitter’s decision to permanently ban Trump in light of his incitement of the Capitol Riots on January 6 underscored the dangerous ability of tech giants to influence and steer political discourse. Trump also oversaw a period in American politics that has resulted in unprecedented distrust of the media, due in part to his baseless allegations that the election was stolen from him. For example, 56% of Americans now believe that “journalists and reporters are purposely trying to mislead people by saying things they know are false or gross exaggerations”.

Europe

As expected, Europe remains the healthiest region of the world in terms of press freedoms. In fact, 14 of the 20 highest-ranked countries on RSF’s press freedom index are in Europe—Norway (#1), Finland (#2), Sweden (#3), Denmark (#4), Netherlands (#6), Portugal (#9), Switzerland (#10), Belgium (#11), Ireland (#12), Germany (#13), Estonia (#15), Iceland (#16), Austria (#17), and Luxembourg (#20).

That being said, RSF did note some worrying trends and incidents in the continent. For example, Hungarian (#92) President Viktor Orbán, like many other countries across the world, has implemented severe restrictions on access to information about the coronavirus, wherein journalists are often charged for spreading “fake news”. Similar approaches have been adopted in Serbia (#93) and Kosovo (#78).

Aside from the pandemic, journalists have also faced censorship, intimidation, or punishment for covering topics like migration. For example, in Greece (#70), journalists are often arrested so as to prevent them from speaking to migrants, who the government is worried may reveal too much information about how they are being treated. Such restrictions were even observed in countries that rank fairly high on the list, such as Spain (#29).

In other countries, like Poland (#64), state-owned media outlets have essentially been transformed into “propaganda outlets”, wherein funding is withheld unless they “toe the government line”.

At the same time, there has also been a rise in attacks on journalists by civilians, which can often result in self-censorship, particularly if the assailants are not punished appropriately or are acquitted entirely. The pandemic, in particular, has increased the frequency of physical attacks on journalists. For example, in Germany (#13) and Italy (#14), reporters have been attacked both by police and civilians while they have been covering protests against coronavirus restrictions and lockdowns.

It is evident that press freedoms are particularly absent in eastern European countries, and the fact that this has been a continued trend for years has pushed some journalists to fight back. For example, in Russia (#150), journalists have repeatedly pushed the government to acknowledge the true death toll from the coronavirus, which ultimately resulted in authorities revising the figure by saying that the death toll was three times the official number. Nevertheless, journalists in the country continue to be censored using the “disinformation law”.

Latin America

In Brazil (#111), President Jair Bolsonaro last year briefly instructed the health ministry to only show COVID-19 infections from the past 24 hours so as to reduce criticism of his handling of the pandemic, which has been nothing short of catastrophic. Even if he has since scrapped that policy, he has continued publicly vilifying journalists and critics of his governance. In fact, his administration’s lack of transparency pushed a number of media outlets to form an alliance whereby they gathered information from the country’s 26 states and the federal districts of Brasilia and published their own public health notices.

El Salvador noted the biggest drop in the index, falling by eight places to 82nd, which RSF attributed to a lack of transparency, “denial of access to public spaces”, “police seizures of journalistic material”, “presidential aides refusing to answer pandemic-related questions at press conferences”, and a “ban on interviews with officials about the pandemic”.

Virtually identical methods were employed in Guatemala (#116), Ecuador (#96), Nicaragua (#121), Honduras (#151), and Venezuela (#148). In fact, Guatemala’s President, Alejandro Giammattei, publicly declared that he wanted to “put the media in quarantine”.

Like Bolsonaro, leaders across several other Latin American countries accused the media of blowing the severity of the pandemic out of proportion and inciting panic. Government-coordinated efforts to undermine journalists through online platforms are also observed in Peru (#91), Argentina (#69), and Colombia (#134).

Unsurprisingly, Cuba, which has close to no freedom of expression or public access to information ranks 171st.

Meanwhile, despite Mexican (#143) President Andrés Manuel López Obrador vowing to tackle corruption, he has often used his press conferences to criticise media reports and journalists he doesn’t agree with. Journalists in the country are frequently attacked and intimidated, particularly when covering alleged corruption or organised crime. Physical attacks against journalists have also been observed in Haiti (#87) and Chile (#54). A total of 13 journalists were killed in 2020 in Mexico, Honduras, and Colombia.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Earlier this year, ahead of the presidential election in Uganda (#125) on January 14, the Yoweri Museveni-led government revoked the press credentials of all foreign journalists. The government also increased the roadblocks for content-sharing and news platforms to publish information. Local journalists have been subjected to intense physical intimidation as well.

This appears to be a trend that has been observed all across the region, with RSF having recorded “three times as many arrests and attacks on journalists in sub-Saharan Africa between 15 March and 15 May 2020 as it did during the same period in 2019.” To the end, the report notes that Africa “remains the world’s most dangerous continent for journalists”.

In several countries, such as Tanzania (#124), the work of reports was impeded because the government refused to release information or statistics on the virus. In other countries, like Eswatini (#141) and Botswana (#38), authorities placed criminal charges on journalists reporting on the pandemic, alleging that they were peddling “fake news”.

Aside from the pandemic, in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo (#149), South Africa (#32), Zimbabwe (#130), and Rwanda (#156), journalists were arrested, intimidated, or gagged for reporting on corruption or organised crime, much like in Latin America. Likewise, journalists in Nigeria (#120) arrested or killed while covering the #EndSARS protests last year.

There has also been a marked increase in government control and moderation of online media and social media platforms, with many outlets arbitrarily having their licenses suspended.

Central Asia

The Nagorno-Karabakh war between Azerbaijan (#167) and Armenia (#63) resulted in the deaths of at least seven journalists.

The region as a whole recorded multiple internet shutdowns, particularly after disputed elections, such as in Kyrgyzstan #79).

Turkmenistan is ranked 178th on the index, which has not been helped by the government’s refusal to admit the presence of the coronavirus in the country. In fact, independent local media is virtually non-existent and others operate in secrecy to leak information to foreign news outlets.

In Tajikistan, anything information about the pandemic that the government deemed to be “false” or “inaccurate” resulted in reporters receiving heavy fines or being imprisoned in an apparent effort to intimidate journalists into parroting the claims of the government, which continues to maintain a suspiciously low case count and death toll for the virus.

The full report can be found here.