India’s Notice and Pakistan’s “Intransigence”

On 25 January, hours before India and Pakistan’s hearing over the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, New Delhi issued a notice to Islamabad to modify the treaty. The statement demanded that the dispute be resolved within 90 days.

Sources in New Delhi claimed that the notice was due to Pakistan’s “intransigence” on the issue, as well as its pursuance of two parallel processes of seeking the appointment of a neutral expert by the World Bank in 2015, unilaterally withdrawing this appeal, and then going on to propose a court of arbitration in 2016.

Both approaches were taken by Pakistan to highlight and address its objections to India constructing two hydroelectric projects — Kishenganga and Ratle — on the rivers Jhelum and Chenab, respectively. Notably, India is yet to participate in the arbitration proceedings.

Despite repeated efforts by India to find a mutually agreeable way forward, Pakistan refused to discuss the issue during the five meetings of the Permanent Indus Commission from 2017 to 2022.

— Kanchan Gupta 🇮🇳 (@KanchanGupta) January 27, 2023

n7

Kanchan Gupta, a senior adviser to the Indian Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, highlighted that Islamabad’s actions contravened the mechanism for dispute resolution under Article IX of the IWT. In addition, by initiating “two simultaneous proceedings,” Pakistan had endangered the treaty by opening it up to “inconsistent or contradictory outcomes” to the dispute.

However, it remains to be seen whether India is looking for a specific modification to the dispute resolution mechanism or using the notice to pressurise Pakistan against blocking its hydroelectric power projects.

Article 12(3) of the Indus Water treaty provides provision for modifying the treaty https://t.co/H7DpC9Gj9l pic.twitter.com/NUDQrkO9Sx

— Sidhant Sibal (@sidhant) January 27, 2023

Pakistan’s Response

Responding to the notice, the Pakistani Attorney General’s (AGP) Office said that the notice was “a demonstration of India’s bad faith” and a means for New Delhi to distract from proceedings at The Hague. The release noted, “The Treaty cannot be unilaterally modified.”

The AGP’s statement reiterated Pakistan’s willingness to resolve the issue through both mechanisms under the IWT — the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which will resolve legal, technical, and systemic problems, and the appointment of a neutral expert to deal with technical issues.

This could be a big jolt to Pakistan. India has issued a notice to amend the Indus Water Treaty. Notice issued on January 25, 2023 gives a chance to Pakistan for entering into Inter Governmental Negotiations within 90 days. pic.twitter.com/bN3BSbhXVi

— Pranay Upadhyaya (@JournoPranay) January 27, 2023

In addition, Pakistani Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mumtaz Zahra Baloch said on Friday said India’s actions were “diversionary” and the procedure at The Hague was in compliance with the IWT.

Road to Current Dispute at The Hague

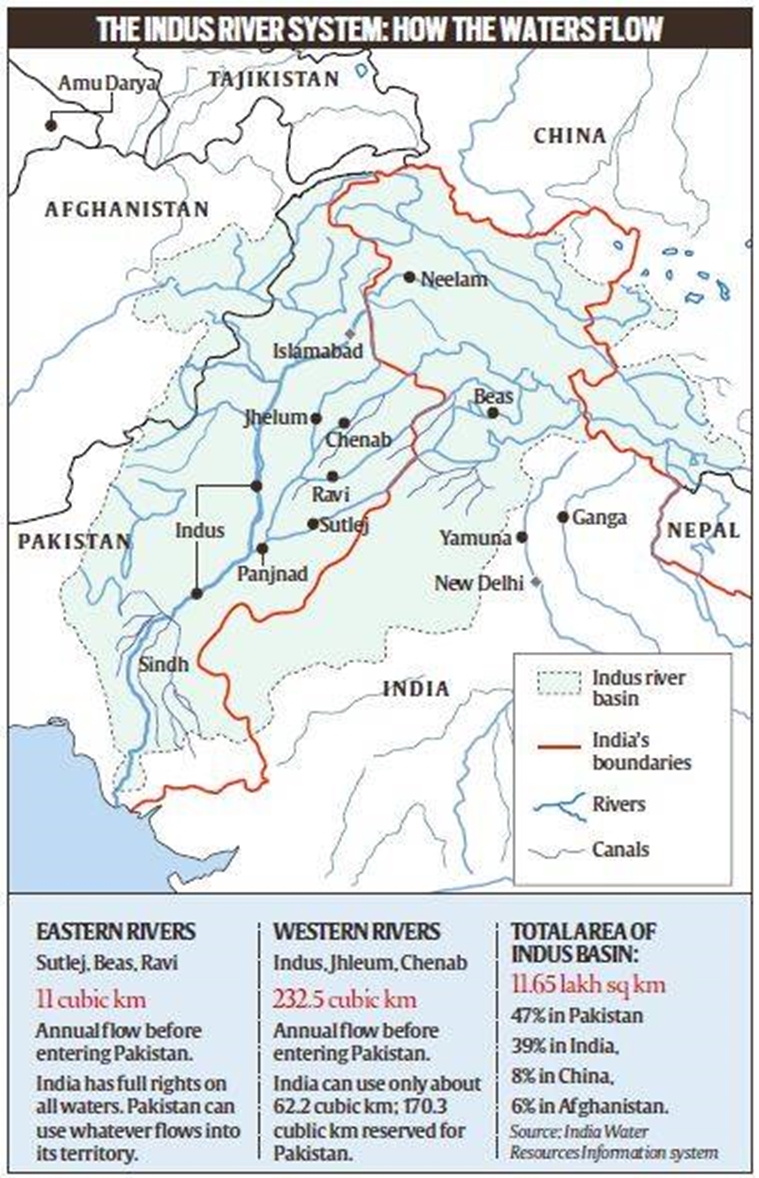

The IWT was signed in 1960. It deals with the Indus River, which originates in China-occupied regions in Western Tibet and is a crucial source of irrigation for farmers in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It crosses India and Pakistan before finally entering the Arabian sea.

As a result of the agreement, control over the western rivers — Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum — have been given to Pakistan. Meanwhile, India controls the eastern rivers — Beas, Ravi, and Sutlej. The Treaty also allows India to establish storage facilities and run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects on the western rivers.

The conflict arose due to India’s proposal to construct the 850-megawatt Ratle hydroelectric plant on the Chenab River and construction of a 330-megawatt plant on the Kishenganga River, which is a tributary of Jhelum River.

Islamabad claims that the projects on the western tributaries would obstruct the flow into Pakistan. Meanwhile, India insists that the proposal are run-of-the-river projects that the IWT permits.

Notably, the IWT demands that a neutral expert attempt to resolve the dispute before the parties approach the World Bank to set up the Court.

However, after Pakistan initiated parallel proceedings via a neutral expert appointment and the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the World Bank recognised the possibility of conflicting outcomes of the two proceedings and suspended its process for the Court of Arbitration in December 2016.

The Indus Waters Treaty is a water-distribution treaty between India and Pakistan, brokered by the World Bank, to use the water available in the Indus River and its tributaries. The Indus Waters Treaty was signed in Karachi on 19 September 1960 by Jawaharlal Nehru and Ayub Khan pic.twitter.com/QlTuCAsNSW

— SRI (@SRI_org) August 21, 2020

Nonetheless, after the two warring neighbours failed to accept a forum to resolve the dispute for six years, the World Bank set up the Arbitration Court and appointed Michel Lino as the neutral expert last October.

On the one hand, Pakistan previously admitted that it had initiated parallel proceedings. However, it claims it made the decision after government-level talks “came to nought.”

On the other hand, India has insisted that the World Bank’s role is “limited and procedural”, and it can only appoint a neutral expert or set up arbitration at the behest of the parties to the IWT.

What Next?

The IWT must be kept separate from India and Pakistan’s geopolitical tensions, which have skyrocketed since the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status in 2019. However, the IWT dispute is, unfortunately, moving away from resolution.

Concerningly, both India and Pakistan have witnessed a drop in the water flowing through Indus’ tributaries, as well as other problems, including water logging and salinity.

The mighty Indus River at Jamshoro in Sindh - in very high flood pic.twitter.com/FN9ZsqwRRA

— omar r quraishi (@omar_quraishi) September 6, 2020

However, the issue has been more pressing for Pakistan, particularly considering its dropping per capita water availability and poor water management mechanisms, which have caused repeated droughts and floods.

Given that the glaciers in the Tibetan region are melting at higher rates, India and Pakistan must work towards an amicable resolution to ensure that climate disasters do not impact the population residing in the area in the future. Water sharing will also be a critical issue for the residents and farmers of the affected regions, with droughts and floods becoming increasingly frequent.