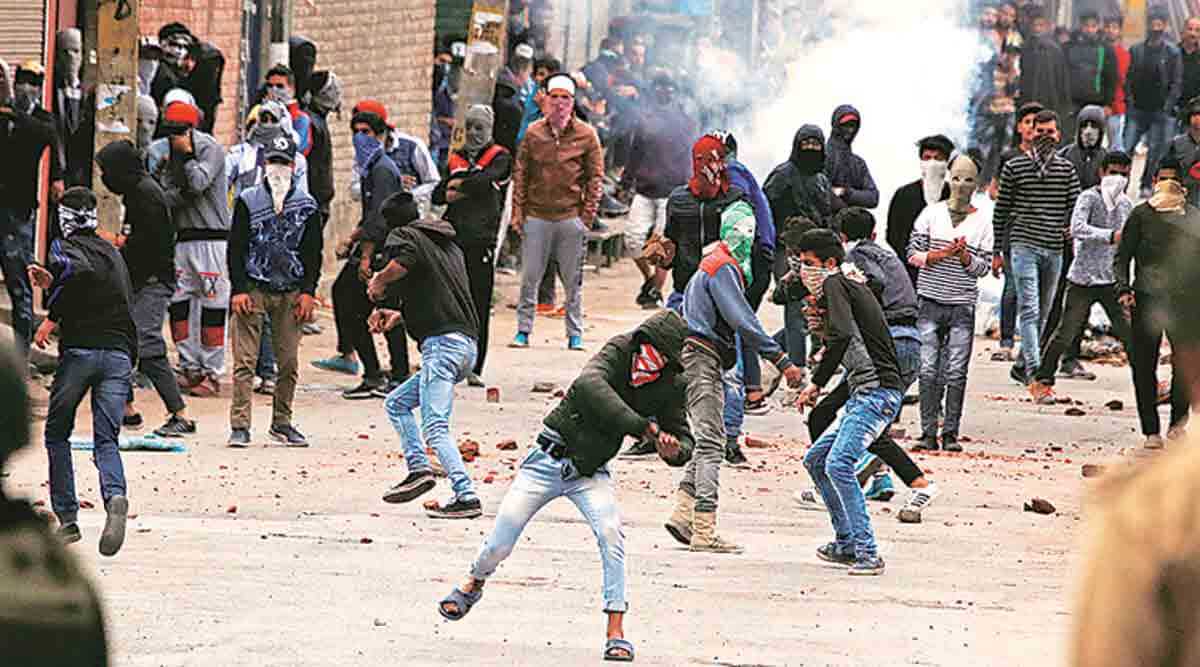

The solution to India and Pakistan’s Kashmir issue has emerged as a head-scratcher for the international community for decades now, and, amidst this confusion and chaos, there are certainly no winners in Kashmir. Both India and Pakistan continue to expend significant chunks of their budgets to counter the security threat in the region. Whereas, for the locals and residents in Kashmir, the decades-long conflict and militancy and insurgency in the region has resulted in severe suffering, and loss of people and property. Despite several attempts to resolve the dispute, such as the United Nations’ Security Council’s (UNSC) resolutions and the convening of bilateral negotiations between various regional stakeholders, violence continues to persist, and policymakers continue to look for the right solution to this complex problem.

Recently, Pakistan’s Human Rights’ Minister, Shireen Mazari, during a webinar organised by a prominent Pakistani thinktank—Islamabad Policy Institute—advocated for a “Good Friday Agreement” (GFA) type solution for Kashmir. The GFA is often applauded for its role in the resolution of the 700-year-long conflict in Northern Ireland in 1998. This is in stark contrast to Pakistan’s previous position on the issue, which has centred around the right to self-determination of residents in Kashmir. Mazari, however, is not the first person to suggest this model of conflict resolution for Kashmir. In 2003, Bill Clinton, who played a crucial role in reconciling differences between the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom (UK), and the political parties in Northern Ireland, also recommended a GFA-like arrangement between the stakeholders in Kashmir. Some Indian academics and political leaders, including Farooq Abdullah and Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, have supported this solution as well.

The proposal undeniably portrays a rosy picture for policymakers looking to bring an end to the continuing violence along the India-Pakistan border. Like Kashmir, the Northern Ireland region was a hotbed for conflict between separatists, who wanted Northern Ireland to be a part of the Republic of Ireland, and the loyalists or unionists, who wanted to retain their allegiance to the UK. The Northern Ireland model, which set up a unique power-sharing model, successfully ended violence in the region since 1998 by reaching a compromise between the opposing factions to allow participation in governance, along with promoting peaceful co-existence. The GFA doesn’t call for any exchange of sovereignties and territories; instead, it focusses on an integrated model. According to the terms of the agreement, the UK, the Republic of Ireland, and the separatists’ and unionists’ groups within Northern Ireland have to be acknowledged as crucial stakeholders in decision-making. Therefore, in a region like Kashmir, which doesn’t have a defined border and has overlapping social and cultural integration beyond their nationalities, such a solution, which focusses on securing co-existence in the region instead of looking to demarcate territorial boundaries, does look justifiable at first glance.

Further, the Ireland deal stipulates that, while Northern Ireland continues to be a part of the United Kingdom, it maintains a great deal of independence and autonomy. For instance, Northern Ireland retains the right to secede from the UK if this intention is expressed through a referendum. Hence, for locals and residents in Kashmir, who often feel alienated, this could serve as a safety net for future negotiations.

Therefore, for Kashmir, where, like Northern Ireland, the unresolved dispute has led to significant losses for all stakeholders in question, the example of the GFA could resemble a light at the end of the tunnel. However, in reality, the key differences between the two situations make a GFA-type suggestion for Kashmir highly idealistic and practically impossible to successfully execute.

To begin with, the GFA was driven by several factors that are absent in the situation in Kashmir. For instance, the agreement came amidst a monumental change in Europe, wherein leaders across the continent were rushing to work towards the formation of the European Union (EU). Consequently, there was a push to expedite the resolution of ongoing border disputes, such as those between Italy and Austria and between France and Spain. Of these border disputes, Northern Ireland’s was the most controversial of them all. However, as both the UK and the Republic of Ireland were among the first few countries to accede to the bloc, their interest in bringing an end to the violence was driven by their interest in securing EU membership and reaping the benefits of regional collaboration.

Conversely, both Indian and Pakistani governments are disincentivised from reaching a compromise as the Kashmir issue is closely linked to the idea of nationalism and, indeed, national identity. Hence, relinquishing any control over Kashmir by the Indian or Pakistani government will be vehemently opposed. Further, with several regional leaders and groups in Kashmir being termed as a threat to “national security” for their involvement in terrorist activities, the countries are also likely to disagree on the participants of the multi-party negotiations, unlike in the GFA, as several regional players are considered to be “freedom fighters” for one side, and “militants”, “terrorists”, or “insurgents” for the other. Moreover, both governments will have to justify their decision to involve such “miscreants” in the talks. With public sentiments on the issue running so high, it is improbable for any political party to endanger their chances of re-election over the negotiations. Hence, in the absence of any motivation for Indian and Pakistani authorities to come together to resolve the dispute, neither governments will be willing to negotiate or compromise.

Moreover, while the GFA solution may have played a crucial role to bring an end to violence in the region, the model has failed to develop an effective governance model. This political instability in Northern Ireland continues to hamper the smooth functioning of the government. For instance, following the 2017 election, the two parties that emerged as the winners were required to reach an agreement and form a government. However, they disagreed on several issues, such as awarding an official status to the Irish language and for holding perpetrators of violence preceding the GFA liable for committing criminal offences. Following this, with the leaders of the two parties refusing to negotiate, there was no government until January 2021. This led to absolute chaos in several aspects of governance, including healthcare, education, and management of public funds. Hence, even if an agreement between the stakeholders is reached, the decades of mistrust will continue to exist and obstruct a peaceful power-sharing model.

In fact, this solution is particularly alarming for India. If the Northern Ireland model is implemented in Kashmir, this would require the border between India and Pakistan in the region to allow for the free movement of people and goods. Further, individuals of the region would also be allowed to hold dual citizenship. This is particularly alarming for India due to its concern about Pakistan’s involvement in terror-funding and money laundering. In the past, India has held Pakistan responsible for several terrorist attacks, such as Uri, Pulwama, the 26/11 attack in Mumbai and the attack on the Indian Parliament. In fact, Pakistan has been put on the “grey list” by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The UN Analytical Support Sanctions Monitoring team, in its 26th report, highlighted the role of Pakistani nationals in spearheading and leading groups, such as the Islamic State and the Al Qaeda, in their activities in the South Asian region. Further, even if the Pakistani government negotiates and ensures their commitment to regional security, Pakistan’s unstable political situation, with a weak government and an alarmingly powerful military, raises doubts about its ability to effectively negotiate on behalf of its people. Hence, opening up borders and forming such close relations with Pakistan could risk insurgency and increased terrorist activities in India, making this solution far from feasible or even acceptable to Indian negotiators.

For Pakistan and those supporting separatism, this solution may work, as it allows room for participation in decision-making, which is something that both parties long for. However, for India, who is secure about its military capabilities and its ability to protect its land against Pakistani threats, there needs to be more incentive to agree to compromise and relinquish any control over a territory over which, for years, they have claimed legal, historical, and political control over. Moreover, the regional disturbances and the growing pressures from China is making India increasingly defensive about its border claims. Hence, even in the unlikely scenario that such a solution is negotiated, there would have to be years of groundwork to revive India’s trust in Pakistan’s negotiation power and good faith, along with providing Indian negotiators with the right motivation and incentives such as regional pressures or trade and economic benefits, without which such a compromise remains unachievable.

No, Kashmir Should Not Become the New Northern Ireland.

Pakistan’s Human Rights’ Minister proposed implementing a GFA-type deal in Kashmir.

August 27, 2020

SOURCE: THE INDIAN EXPRESS