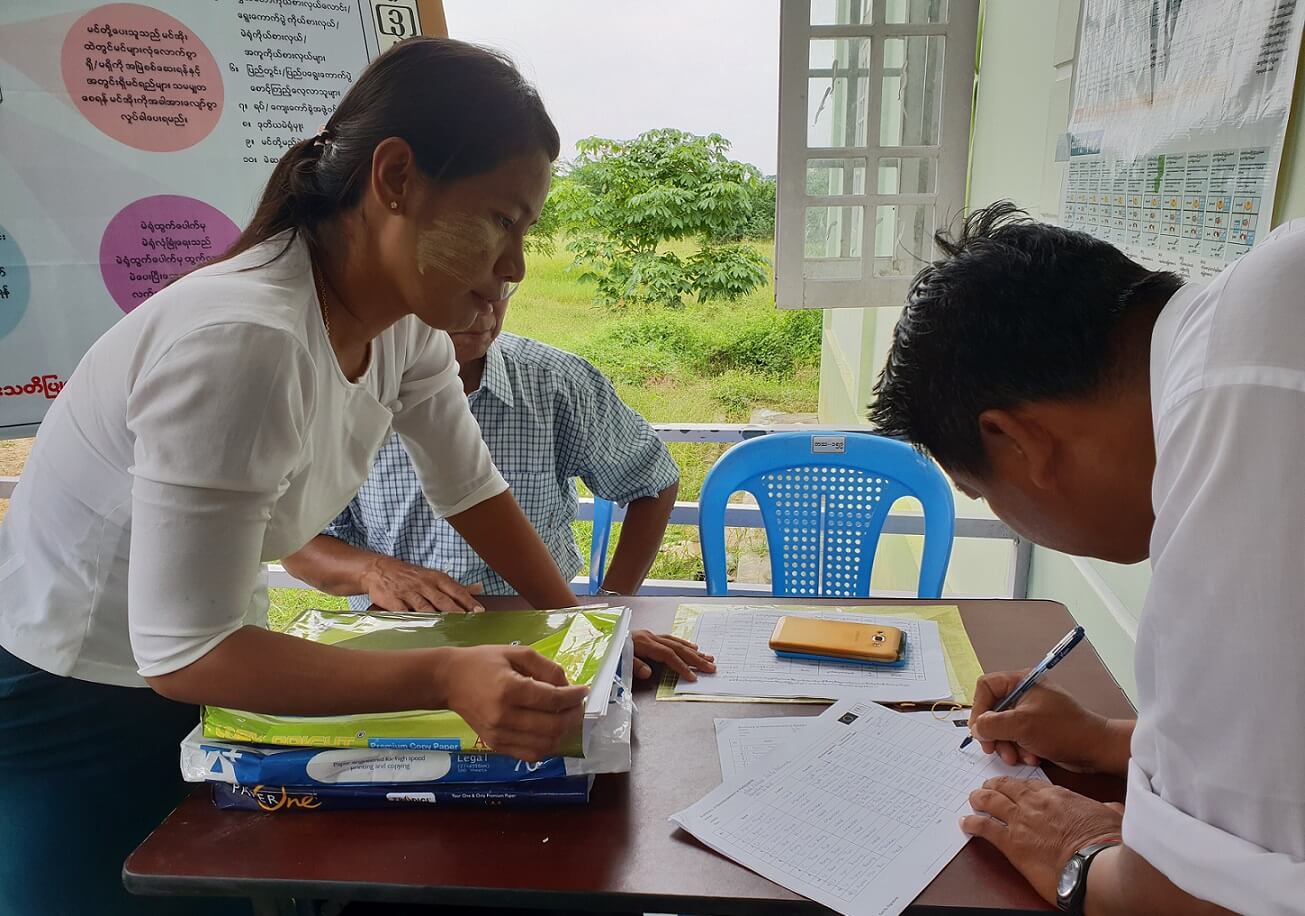

Myanmar is scheduled to hold its second free election on November 8 this year. Advance voting in some locations such as quarantine centers, residences, and for migrant workers in Thailand, had already begun from October 29. However, voters are dismayed over the manner in which the election is being carried out. On the very first day of the voting itself, there were concerns in several townships over trouble keeping votes confidential and complains from voters about open envelopes.

U Kyaw Moe Kyi, a member of the Yangon Region Election Commission, attributed the open envelopes to the paper quality. However, while he conceded that some of the envelopes were open from the sides because of the poor quality of paper used, he said that it was more important that the voter slips inside remained intact. If the voter slips had no signatures, or were torn or smeared with ink, they stood a chance of being rejected.

Early voting also began in Thailand, where over 1 million migrant workers reside. Voters have shown dissatisfaction with the lack of aid offered by the Thai government in setting up more polling booths, due to which several thousand of them were unable to carry out their civic duty. Only about 30,000 people applied for advance voting and only 20,000 turned up to cast ballots. One of the reasons for this mismanagement was the lack of voting locations outside of Bangkok or Chiang Mai. Had the government of Myanmar made more polling stations available in other cities where migrant workers work, more people may have been able to reduce travel costs and cast their vote.

Another major reason for anger among voters is the fragility of the right to vote. Several Muslims voters, who form a significant portion of the population, have had their citizenship stripped and are barred from voting or running for parliament. Rohingya Muslims, who hold temporary registration certificates, known as "white cards," were allowed to vote in the 2010 general elections. But in 2015, in a move that further exacerbated Rohingya identity in Myanmar, the military-backed government announced that white cards, which were previously provided to many minorities as provisional citizenship documents, would expire. These previously accepted white cards were considered no longer eligible and Rohingya Muslims were informed that they were not allowed to vote that year.

On October 20, the election commission announced its decision to cancel voting in parts of the country, was based on recommendations by the government, the Defense and Home Affairs Ministries, the military, and the police. The commission, however, did not provide information on the criteria it used, which should have been clearly determined and explained after due consultation with candidates and parties. There are concerns about elections going forward in some areas that have a high level of conflict or that have experienced security issues. In 2020, cancellations in Rakhine State account for up to 1.2 million disenfranchised voters, not including the 600,000 ethnic Rohingya who have been barred from voting.

The divide between Myanmar’s majority and ethnic populations remains deep, and growing disenfranchisement of ethnic minorities appears to hinder Myanmar’s fledgling democracy.

Myanmar’s Election Practices Met with Voter Disapproval Over Concerns About Malpractice

As Myanmar begins early voting for its second free election, voters are concerned about malpractice.

November 2, 2020

SOURCE: International IDEA Myanmar