'Education is not a privilege; it is a right', shout the sloganeering Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) students protesting an exorbitant fee-hike proposed by the Vice Chancellor of the University.

The move threatens to undermine efforts to address income and social inequality in the country, as accessible, affordable, high-quality higher education provides the framework for a skilled labour force to escape cyclical poverty. One needs to look no further than Ramjal Meena, a 34-year-old security guard at the university, who cracked the JNU's exam for B.A. (Honours) in the Russian language.

Therefore, it is crucial to understand the JNU protest on fee hikes within the broader framework of the politics of knowledge in India and the changing state-university dynamic.

Under the new hostel charges, JNU will become the most expensive Central University; rent has been increased from Rs. 20 per month to Rs. 600 for single occupancy, and from Rs. 10 to Rs. 200 for double occupancy. A service charge of Rs. 1,700 per month has also been introduced, and the refundable mess security was hiked to Rs. 12,000.

Following the protests, mess charges have been slashed to Rs. 5,500 and a 50% concession has been offered to students below the poverty line (BPL) on room, utility and service charges.

However, students are demanding a complete rollback of the new fee structure. As per a newspaper report, even with the revised charges, non-BPL students will have to spend Rs. 62,500 and Rs. 60,700 per annum for single and double occupancy, respectively.

Even for BPL students, who make up 40% of JNU's student body, annual rates would be approximately Rs. 46,000. For BPL students to shell out Rs. 4,000 per month when their parental monthly income is less than Rs. 12,000 is particularly challenging.

Critics of the protests, who term the students ‘freeloaders’, ‘urban naxals’ and the ‘tukde-tukde gang', not only de-legitimize their concerns but also trivialize their demands. Moreover, the common perception that JNU‘s hostel fee structure is the lowest is highly contested. As per a report by Indian Express which has studied the fee structure of top 10 Central Universities, JNU’s old fee structure was not the lowest. Therefore, the narrative that students are protesting minimal increases to already low fees is unfounded.

This nationwide trend of fee hikes has galvanized students not only in JNU, but also in the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), and the University of Delhi. This transformation of the education sector is driven in large part by declining state support for–and interest in–higher education, as illustrated by government proposals to increase fees for the All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS).

Fee hikes reduce social mobility and threaten to derail India's educational progress whereby the Gross Enrolment Rate (GER) at higher education level has increased from 8.1% in 1991 to 26.3% in 2018-19.

In spite of such figures, 79.30% of people between 20 and 24 do not attend any educational institution, with the leading cause being financial constraints. Similarly, while social composition for higher education has improved, it still remains skewed. In the year 2018-19, male enrolment (51.36%) was higher than female enrolment (48.64%). Furthermore, Scheduled Caste students constituted 14.89%, Scheduled Tribe students 5.53%, Other Backward Classes 36.34%, and Muslims 5.23% of total student enrolment.

An already bleak social composition in universities is at risk of being worsened by actions like those of JNU's Vice Chancellor who, in 2017, reduced the university's deprivation points, which facilitates the entry of marginalized students–who have regional, economic and gender disadvantages–by awarding them grace marks. This has drastically impacted the student composition in the university; admissions from rural areas have declined from 42.70% in 2014-15 to 28.24% in 2017-18. Similarly, the percentage of students with parental income less than Rs. 12,000 has reduced from 44.2% in 2014-15, to 19.84% in 2017-18. There has also been a sharp reduction in students from the 'reserved' categories.

Therefore, by increasing fees, universities threaten to halt progress in female higher education which is already seen as a minimal priority in a patriarchal Indian society, and further stratify income inequality among minorities and marginalized groups. Furthermore, such elitist moves politicize knowledge by limiting access to information and education for the marginalized sections of the population.

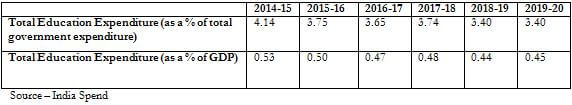

Considering its aims to exploit its ‘demographic dividend’ by exponentially increasing in its working-age population, it is vital for the government to invest in higher education. Instead, we are witnessing a continuous decline in public expenditure and growing privatization in education.

With a declining education budget, taxation has funded 70% of expenditure on education since 2015. However, the CAG report highlighted that the tax returns collected for secondary and higher education have not been fully utilized, with the unused amount since 2007 amounting to Rs. 94,036 crores.

In response, the Indian government has announced the creation of a Higher Education Financing Agency (HEFA) as a new funding authority, in collaboration with Canara Bank. This is intended to shift the grant-based funding model to a loan-based one for publicly funded institutions by requiring universities and colleges to mortgage their assets to access additional funding.

However, the withdrawal of public funding and the establishment of a market-based education financing structure will result in a massive fee-hike and increase the economic burden on the students. Therefore, without sufficient institutional support, growing privatization is bound to hinder access to education for the underprivileged, marginalized, and vulnerable sections of Indian society.

Hence, the JNU protests are not just about an increase in hostel fees. Rather, they are part of a greater struggle to encourage social mobility, reduce privatization of education, challenge the autonomy and structures of educational institutions, and encourage governmental prioritization of higher education.

Plurality and diversity of the student community are vital to democratize academia and to fight inter-generational reproduction of social and economic inequalities. Higher education contributes to accelerating economic growth and is also crucial in enabling upward social mobility and transformation. Thus, direct state intervention is essential to provide accessible education to every citizen.

A large, vibrant, and diverse student body has the power to encourage democratic participation and facilitate deliberation of social and political matters. Student protests both in JNU and nation-wide thus attempt to deter the unravelling of the egalitarian and inclusive nature of universities, and by extension, of Indian society.