Technology is becoming increasingly more integrated into every aspect of human life, and nothing has made that clearer than the coronavirus outbreak. As lockdowns keep millions confined to their homes, our whole world has now become virtual, as we depend on our smartphones, television sets, laptops, and e-readers to help us get through prolonged periods of self-isolation. The trouble, however, is that our insatiable demand for electronics is creating the world’s fastest-growing waste stream.

Our increased dependence on electronic equipment and the simultaneous strides in technological innovation is coupled with the reduced life spans of our devices. Not just that, but options for repair are extremely limited as well. Companies like Apple, or Sonos, for instance, regularly update the design or software for their product, and discontinue support for older models, so it often becomes easier (and significantly cheaper) to buy a new device, rather than to repair an old one. This inevitably means that millions of electronics end up in the trash every year.

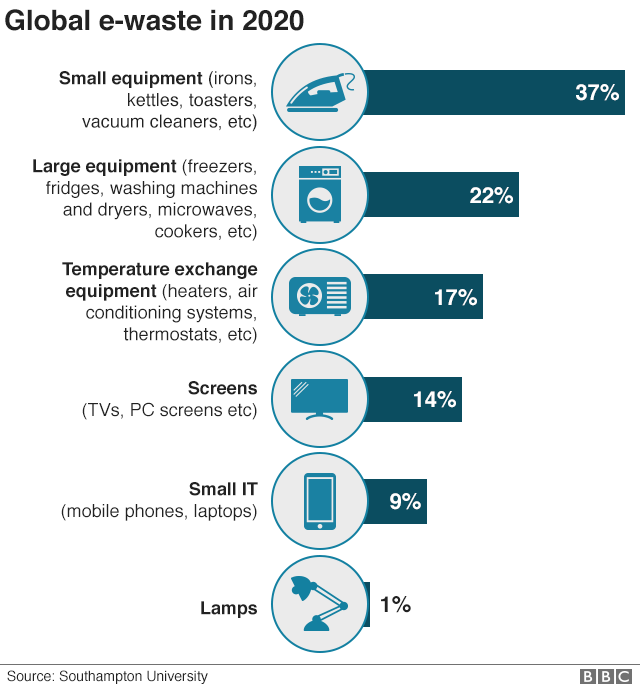

The latest data, according to the UN’s Global E-Waste Monitor 2020 Report, suggests that a staggering 53.6 million tons (Mt) of e-waste were generated in 2019, 21% more than just 5 years ago. To put that number in perspective, 53.6 Mt is more in weight than that of all the commercial aircraft ever built throughout history, or 4,500 Eiffel Towers, and enough to cover an area the size of Manhattan. The report also projected that the number would reach 74 Mt by the end of the decade, which means that in just 16 years, the rate of e-waste will have doubled.

Strengthened global recycling systems have been touted as the way forward to effectively address what the UN refers to as an exponentially growing “tsunami” of electronic and electrical waste. Discarded devices are made up of a mix of materials that includes gold, silver, copper, platinum, palladium, lithium, cobalt, and other valuable elements. The estimated value of these raw materials in the e-waste generated last year was $57 billion, and experts have envisioned a “circular economy” for electronics that treats e-waste as a vital resource, generates less waste, and spurs new forms of employment, economic activity, education, and trade, thereby creating a sustainable future.

The task at hand, however, isn’t easy. Although multiple countries—78 so far—have introduced national e-waste policies or regulations, enforcement still remains poor, and the lack of investment and political will does not yet stimulate the proper collection and management of e-waste. The current rate of responsible e-waste recycling stands at an abysmal 17.4% worldwide. Additionally, many nations actually ship e-waste abroad, where, instead of being recycled, usable parts are repurposed, and minerals are extracted. The biggest e-waste producers, like the US, for instance, have no federal laws that mandate the recycling of electronic waste or forbid it from being exported. The US is also one of the only (9) nations that have not yet ratified the Basel Convention, which regulates the transboundary movements of hazardous wastes.

These shipments of electronics to the developing world—which is where a majority of them land—are justified as a means to give second and third lives to devices and help bridge the world’s digital divide. However, the cloak of ‘reuse and repair’ is often used to hide illegal exports, or dumping of e-waste, which accounts for about 7-20% of the total e-waste produced. Setting up formal recycling is an expensive endeavor that involves disassembling the electronics, separating and categorizing the contents by material, and cleaning them. Items are also shredded mechanically for further sorting with advanced separation technologies, and companies are required to adhere to health and safety rules, and use technologies that reduce the negative impacts of e-waste on health and the environment. To avoid bearing such costs and undergoing cumbersome regulatory processes, countries and big industries illegally export their e-waste to low and middle-income countries, where recycling is much cheaper.

This practice, however, comes at an enormous cost to local populations, as these gadgets also comprise toxic heavy metals like lead, mercury, cadmium, and beryllium, polluting PVC plastic, and hazardous chemicals, which can pose serious risks to human health as well as the environment if improperly treated. Unfortunately, methods used for this informal recycling and ‘mining’ are almost always unsuitable — in some places, for example, gold is recovered by bathing circuit boards in nitric and hydrochloric acid, poisoning waterways, and after, whatever is not used is dumped in the ground. Men, women, and children engaged in such work often have no idea that they are handling hazardous materials, and do not wear any protective equipment. However, informal recycling offers livelihoods to many who engage in dismantling, refurbishing, repairing, and reselling used electronic devices, and is widely prevalent in various countries like India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ghana, and the Philippines, to name a few.

Of course, a focus on proper and responsible recycling is an important step to battle the growing e-waste crisis and reduce its impact on human health and the environment. Electronic giants—like Apple, Google, and Samsung, among others— have set ambitious targets for recycling and for the use of recycled and renewable materials, and have even developed and introduced new technologies to make the process faster and more efficient. Four years ago, as a symbol of its commitment to the environment, Apple launched ‘Liam’ (upgraded to ‘Daisy’ in 2018), a robot that could dismantle an iPhone in just 11 seconds, and recycle about 1.2 million units a year, which looks like an impressive number until you realize that Apple had sold 231 million new iPhones the year before. Hopping on the bandwagon to “go green” becomes symbolic at best then because the efforts to sustainably reclaim used devices simply cannot keep pace with the massive consumption and production rates for new devices. The UN report noted that the total weight of global electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) consumption increases annually by 2.5 million metric tons (Mt), further reinforcing the fact that relying solely on recycling is not a solution and will barely make a dent in getting waste under control.

While recycling is useful, it is important to recognize the underlying causes of the surging e-waste problem to develop more effective approaches to tackle this crisis. Intentional obsolescence of devices, which drives the profits of the technology sector, is at the heart of the issue. Extension of the life of these gadgets and appliances, through maintenance, refurbishment, and reuse will be a crucial step forward in reducing the negative environmental impact of such technologies. Investment opportunities are now increasingly contingent on a commitment to a cleaner global economy, which can incentivize firms to do more, and better. Governments are taking action on this front as well. In October last year, the EU adopted new ‘right to repair’ standards, requiring companies to make appliances longer-lasting, and supply spare parts for the machines for up to 10 years. The UK government has pledged to do even more post-Brexit. In February this year, France’s Directorate-General for Competition, Consumption and the Suppression of Fraud (DGCCRF) fined Apple 25 million Euros ($27 million) for intentionally slowing down certain models of the iPhone, and not informing customers about it. In 2017, after facing similar complaints about swiftly aging batteries, the company publicly apologized and reduced the cost of having an iPhone battery replaced, making it $29 for the whole of 2018. That was down from the previous $79 and current battery replacement price of $69.

At the local level, there are consumer-led initiatives aimed to ease the repair of devices to prolong their lifecycles. Organizations like The Repair Association in Washington DC and The Restart Project in London are important players in the fight against e-waste. Such enterprises can also help normalize buying refurbished electronics in lieu of new ones, which can help contribute to lesser pollution levels. Given the glacial pace of any kind of policy reform, supporting efforts to extend the lives of electronics to keep them from flooding landfills while simultaneously strengthening national and international regulatory and compliance frameworks for e-waste management may be the most practical and comprehensive approach to address this challenge effectively.