In the midst of all the political turmoil in India, peoples’ plates are still missing a key ingredient–onions. The bulb crop, as of December 10, was being sold at a market rate of INR 101.35 per kg, compared to INR 55.95 per kg last month, and INR 19.69 kg last year.

The main reason for the sudden spikes and drops of onion prices is its supply and storage cycle. The Rabi onion, produced primarily in Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan, is grown from October to March and is stored from April to October for consumption in the market. Around 65% of the annual produce of the crop is stored for consumption and export. The next harvest of the Kharif onions from Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka is supposed to increase supply from August to September, after which a late Kharif from Maharashtra in October and Gujarat from December begin to arrive in the market.

But this year, due to the late onset of the monsoon and excessive flooding, Rabi stored by farmers and traders was severely damaged, as were the standing Kharif crops. As a result, Rabi prices skyrocketed. To counteract this, in June, New Delhi withdrew its 10% export incentives on the crop to keep domestic pricing in check.

By mid-September, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry amended the Minimum Export Price (MEP) on onions in an attempt to curb local prices of the crop. The concept of MEP, which is practised by many member states of the World Trade Organization (WTO), refers to the minimum price below which exporters cannot sell any product from India. This is ideally supposed to keep a check on price rises and availability of the commodities in local markets as well as counter disruptions in their production.

MEPs are usually imposed for short durations and are to be removed when domestic prices and supply are under check, helping farmers and exporters sell their goods at better prices. But many exporters said that the new price of INR 60,376 ($850) per metric ton was too high and encouraged major importers to look to China and other sellers for their onions.

Hence, by the end of September, the Centre decided to ban the export of the crop altogether with the hope that prices would moderate from November with the arrival of new season crops. This ban has been extended until February. This is crucial since India is the world’s largest onion exporter–in 2018-19, we exported 21,82,826 metric tons of fresh onions to the world, valued at INR 3,467 crores ($498 million).

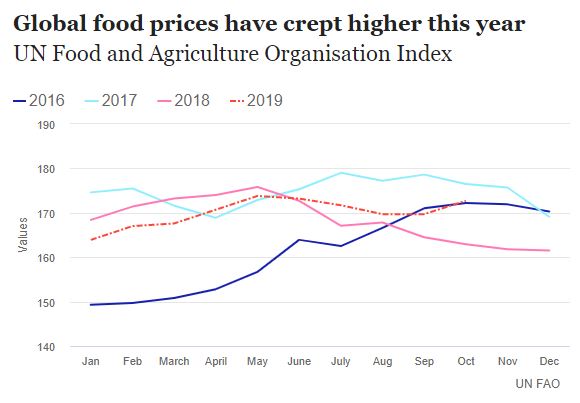

The ban on onion exports has also contributed to the global phenomenon of increasing food prices, especially in Asia.

In 2017, Bangladesh bought almost 60% of India’s onion exports, valued at roughly $60 million. Due to this year’s export ban, Bangladeshi consumers are paying the highest they have paid for onions since 2013–$1.42 (120 taka or INR 100.50) per kilogram–because other exporting countries in Asia and Europe are taking advantage of the Indian ban and raising their own asking prices.

In Sri Lanka, onion prices have nearly doubled since the Indian export ban, and the country has, for the first time, begun importing from Egypt and the Netherlands. Sim Tze Tzin, the Malaysian Deputy Minister of Agriculture also expressed his expectations for the Indian onion export ban to be temporary.

The Metals and Minerals Trading Corporation of India (MMTC) has arranged imports for around 11,000 tons of onions from other countries like Turkey and Egypt to bring down the prices of domestically produced crops. In the next few weeks, the new Kharif crops doubled with the imports will flood the markets and onion prices will go down again. But is this back and forth and artificial manipulation of international trade sustainable in the long run?

These moves by the Government have followed a familiar cycle over the years–onion prices hit the roof due to natural disasters, the government imposes export restrictions and clamps down on hoarding, and prices go back down, mainly due to the introduction of the latest domestically produced crop in the market. After this, farmers begin to increase their support demands from the government, forcing them to ease trade restrictions again, thereby perpetuating the cycle.

These cyclical fluctuations harm the farmer and benefit middlemen the most. In 2018, India produced around 23.5 million tons of onion, but only 14 million mt. were consumed. In a case like this, export is absolutely necessary to manage surplus and maintain prices to ensure profitability for the farmer.

Indian traders have also expressed concerns over the Government’s inconsistent policies and fear losing their market to Egyptian and Chinese suppliers. They have called for the reintroduction of export incentives to improve the income security of farmers.

As an alternative to the MEP, the Ministry of Finance can step in to impose an export duty on onion trade. This kind of a fiscal levy is a non-discretionary way of ensuring that the exchequer revenue increases.

Furthermore, the Government must tackle issues at the core of this cycle rather than resorting to measures like export bans. The core issue of the onion crisis, as mentioned by Danish Shah, a Maharashtra-based onion exporter, is the management of excess production, since there is no dearth in production levels. This means finding effective methods of managing, storing, and distributing surplus crop urgently.

Since 35-40% of India's produced onions are lost in storage wastage, it is imperative that the government invests in new technologies to ensure and create sustainable facilities for the storage of excess crops. It should also look to keep a buffer stock of at least a million tons to counteract indiscriminate hoarding.

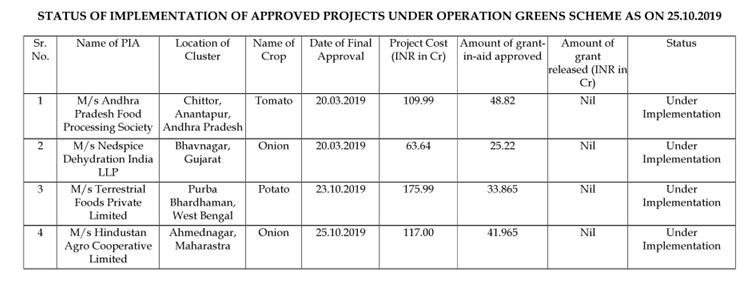

In 2018, Operation Greens, a 500-crore scheme was announced by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries to address the fluctuating prices of tomatoes, onions, and potatoes. This included a special emphasis on the development of agro-logistics, creating appropriate storage capacity linking consumption centre, and improving farm gate infrastructure; however, the scheme is yet to take off on the ground.

Source: Ministry of Food Processing Industries

Furthermore, while the New Agriculture Export Policy includes transport subsidies for the export of agricultural commodities, onions were left out from the list due to their high pricing at the time the policy was drafted. The bulb must be included under the ambit of this policy as the Minimum Support Price (MSP) given to onion farmers is currently not enough to meet their transportation needs even domestically.

In addition to this, most parts of the country, the onion trade falls is controlled by a few big traders; manipulation and cartelization are prevalent despite administrative efforts to curb it. The Government must focus on systematically dismantling this internal hegemony of the onion trade rather than controlling international markets.

The current model is ineffective in creating a long-term change in the distribution and trade of onions as it puts the needs of the consumer before the farmer. More than that, to deprive its trading partners of an essential crop may not be in New Delhi’s best strategic interest in the long run as constantly fluctuating trade policies can hamper Asian dependency on India for the crop as they look elsewhere for stability in distribution and pricing.

A more inward approach must be taken to tackle the issue of onion distribution and storage rather than relying on international markets to stabilize prices. Existing policies aimed at easing the price burden for farmers should be implemented with immediacy before the sowing of the next season. Else, this cycle will continue next year, especially in the backdrop of a nation-wide economic slowdown, affecting the already debt-inflicted farmer the most.

Reference List

Bhosale, J. (2019). A problem of plenty: India's onion mess. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/a-problem-of-plenty-indias-onion-mess/articleshow/71546979.cms?from=mdr

Chandrashekhar, G. (2018). Why the minimum export price is irrelevant?. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/markets/commodities/why-the-minimum-export-price-is-irrelevant/article10048506.ece

Hussain, S. (2019). Onion Crisis Reveals How Little the Government Can Do When the Chips Are Down. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://thewire.in/agriculture/onion-crisis-price-rise-storage

Lynch, R. (2019). Why India's ban on onion exports could bring the world to tears. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2019/11/26/will-rising-food-prices-leave-bad-taste-world-economy/

Reuters. (2019). After India bans onion exports, Asia has eye-watering prices. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/india-bans-onion-exports-asia-eye-watering-prices-1605648-2019-10-02

Sharma, A. (2019). Hurting the Farmer, Minimum Export Price Imposed on Onion to Curb Local Rate Ahead of Key Elections. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://www.news18.com/news/business/hurting-the-farmer-minimum-export-price-imposed-on-onion-to-curb-local-rate-ahead-of-key-elections-2308691.html

Wadke, R. (2019). Onion prices: Traders make a killing even as onion imports from Egypt arrive. Retrieved 18 December 2019, from https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/onion-prices-traders-make-a-killing-even-as-oinion-imports-from-eqypt-arrive/article30104309.ece

Image Source: Dhaka Tribune