India has historically had a lacklustre record at the Olympics. Since its first stint at the Summer Olympics in 1900, India has won just 33 medals. For a country with a population of almost 1.3 billion, this counts towards the worst population to medal ratio at the Olympics. Meanwhile, China, which has almost the same population, has won over 600 medals since 1924. Similarly, all other major world powers seem to win Olympic medals proportional to the influence they wield in global affairs. For example, the top five countries on the medal tally at this year’s Tokyo Olympics, after China and the United States (US), are Japan, Australia, and the United Kingdom (UK). With the Tokyo Olympics having drawn to a close and as we look ahead, it brings back the question of how India’s low medal count impacts its international stature as a rising political and economic power.

India’s failures at the grand sporting event can be attributed to a variety of reasons. Duke University’s Anirudh Krishna and Eric Haglund, for instance, argue that not everyone in the country has equal access to competitive sports, with many turned away from Olympic sports simply due to ignorance, disinterest, disability, deterrence, or lack of information about opportunities. Furthermore, relatively low exposure to sports at the primary school level inhibits the translation of sporting experiences in formative years into professional participation in sports. At the same time, the focus on education in India is immense and enough to steer potential athletes away from sporting life.

Moreover, while India may be the ninth-largest economy globally, it does not dedicate a sufficient proportion of its wealth to nurturing sporting talent. Winter sports or traditionally expensive sports such as equestrianism, golf, rowing, and sailing require expensive equipment and facilities and therefore tend to be dominated by developed countries. However, even less expensive sports in India face problems of accessibility to coaching and training facilities.

Thomas Bach, the chairman of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) wrote in The Guardian last year that the Olympics are “not about politics.” “In the Olympic Games, we are all equal. Everyone respects the same rules, irrespective of social background, gender, race, sexual orientation or political belief,” he went on to say.

However, while the games have historically been hailed as the celebration of the athletic spirit and international unity, the truth is that success at the games has also long been a way for countries to flex their soft power. It also goes without saying that hosting and being successful at such a large scale event offers countries an unparalleled means of both building and projecting status.

In this respect, the final medals tally has time and again made it apparent that only the most powerful and influential nations feature among the biggest medal winners. Olympic success, therefore, paves the way for countries to be perceived as successful and share the stage with other powerful nations. While there is no way of measuring the impact of this success, it no doubt informs the opinions of the global community. The glory that comes with exercising such soft power becomes apparent when considering the budgets top countries allocate to Olympic sports. Hence, while India’s failures at the Olympics may not necessarily in and of themselves impede its ability to project and accrue soft power, it does perhaps illustrate that it doesn’t currently possess this power, at least not to the degree of the countries it aims to rub shoulders with.

Winning multiple medals at the Olympics is not just a reflection of a country’s athletic prowess, but also a reflection of its economic prosperity and ability to spend on secondary priorities. Countries like India end up spending a majority of their annual budget on issues like sanitation, food distribution, and defence.

To put this in perspective, two years prior to the originally scheduled Tokyo Olympics 2020, former Sports Minister Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore stated in Parliament in 2018 that the central government spends a total of 3 paise per day per capita on sports. In comparison, a report in the newspaper China Daily claimed that the Chinese government spends around Rs 6.1 per capita per day, which equals almost 200 times more than India.

Nevertheless, just because India is unable to allocate a large proportion of its budget to sports training and facilities does not mean that it must lag behind. Several countries poorer than India, such as North Korea, Ethiopia, Kenya, are able to win far more medals at the Olympics by simply changing their approach. This has been possible because they have dedicated all their financial, human, and infrastructure resources to honing their natural strengths and talent for niche sports.

For instance, Ethiopia invests in running, which accounts for all 46 of its Olympic medals. Most of them come from long-distance running, including this year’s gold in the men's 10,000-meter race. Jamaica has won all but three of its 68 Olympic medals in sprinting events. Similarly, Cuba targets boxing and has won several medals in that sport. This targeted approach has helped poorer or smaller nations stand out despite their shortcomings.

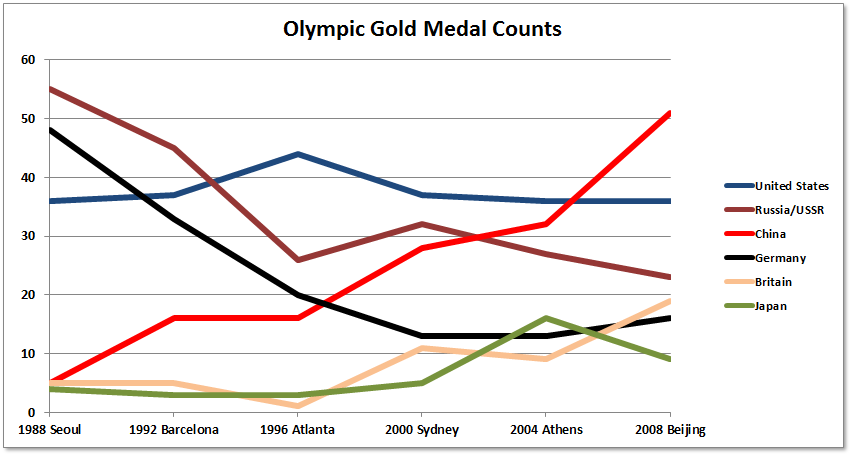

In the same way, China scouts tens of thousands of children for full-time training at more than 2,000 of its government-run sports schools and has also focused on sports that are underfunded in the West, such as table tennis, shooting, diving, and badminton, or sports that offer multiple Olympic gold medals, such as weight lifting, in order to maximise its gold medal count. The graph below is proof that China’s medal tally has consistently risen every Olympics from following this approach and in doing so given it another avenue to match or compete with the US.

Based on these success stories, India must acknowledge its financial constraints and limitations by narrowing its focus to sports that do not require as much capital or infrastructure to gain a competitive edge. “We should play all kinds of sports but should concentrate more in identified 10-12 sports so that we can win medals in those sports,” former Finance Minister Arun Jaitley said before the 2016 Olympics. And although India does hold a high stature in cricket, the sport is not played at the summer Olympics, except once in Paris’ 1990 Olympics. Therefore, it’s time for India to follow through with Jaitley’s advice and diversify funding outside of cricket to a few sports that it can gain a natural competitive advantage in, such as badminton, shooting, wrestling, and weightlifting. While India faces tough competition internationally and steep challenges internally, a revamped strategy could act as a critical stepping stone in expanding its political stature at the grand sporting event.