Last month, I had the opportunity to attend an International Symposium for Action at Mumbai’s Kishinchand Chellaram College on the subject ‘Is Mahatma Gandhi Possible?’ The two-day conference featured eminent figures from India’s political sphere and civil society, who discussed various aspects of Gandhian thought and action and its possible positioning in the current political realities of India. As we celebrate Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary, it is imperative that we engage in asking fundamental questions about the relevance of his teachings, which have inspired similar movements across the globe, but at the same time have been subject to various critiques.

Remarks by Keynote Speaker Dr. Ashis Nandy

In a 2010 book titled Speaking of Gandhi’s Death, Ashis Nandy is quoted as saying, “Today, there is an all-round attempt to make Gandhi respectable. I see a lot of young faces in front of me. I hope you will avoid the temptation of seeing Gandhi as someone respectable, as somebody that your parents would like you to be like. I would rather want you to see Gandhi as disreputable, unpredictable, at the margins of sanity, and at the margins of everyday life; someone who dares to ask you to look even at your everyday life and your public life, and ask, is it possible for us to envision, to re-visualise or imagine a different kind of public or private life? Is it possible to live everyday life and yet look beyond its everydayness, and is it possible to contaminate your everyday life or the life of the people around you with that vision?”

Nine years later, Nandy still holds on to this vision of Gandhi. At the Symposium, he enlightened the audience with a three-pronged historical approach to Gandhi, drawing from various written works. Firstly, he referred to the 1938 novel Kanthapura by Raja Rao, which is set in a small, unidentifiable Indian village where the Gandhian movement and approach to the freedom struggle enters the village, almost by accident. The story that unfolds thereafter is of individuals in the village, who slowly but unwittingly become more and more Gandhian. Nandy opined that through the novel, Rao is making the point that in our civilization, every individual has the potential of becoming Gandhi; maybe not a ‘full’ Gandhi because every Gandhi is different, but that the option of becoming Gandhi is implicit and bestowed upon us.

Secondly, Nandy said that even before Rabindranath Tagore had heard of Gandhi, he reflected Gandhian characteristics and mentions the possibility of the appearance of someone like Gandhi in several works which have been documented in the Bengali book Rabindra Sahitya Gandhi Choritro Purvabhas (translation: Inklings of Gandhi’s Character in Tagore’s Writing). Nandy claims that there is an anticipation in Tagore’s writings that a Gandhi-like character will emerge, and this emergence is cast into the character of a rajarshi — a ruler king who is also a revolutionary simultaneously. This representation of Gandhi as a trait entered the poetry and plays of one of Indian literature’s most sensitive minds long before the man himself, and Nandy says that this is proof that Gandhi is always possible. “If there are 1.2 billion possibilities, then of course it is a certainty that somebody of that kind may emerge not as a person, perhaps, but the traits, our heritage, our civilizational heritage will assert themselves despite all efforts”, he said.

Nandy went on to opine that in a battle between a civilization and a nation-state, the civilization ultimately manages to destroy the nation-state if it deviates from the essence of the civilization’s principles and ethical frameworks. He referred to another novel, Gora, in which Tagore indirectly cast a character based off his close friend Brahmobandhav Upadhyay, a Bengali revolutionary who could be considered the unrecognized father of Hindutva. Apparently, the character of Gora is that of a Hindu fundamentalist who later realizes that his biological parents were actually foreigners; Nandy says that he does not know that he is “genetically a Western product”, just like the ideas of nation-state, nationalism, and nationality, which play different roles in human personality than patriotism and loyalty. The shift of Gora from a radical element to a more peaceful and accepting individual is, according to Nandy, the coming of Gandhi in his character.

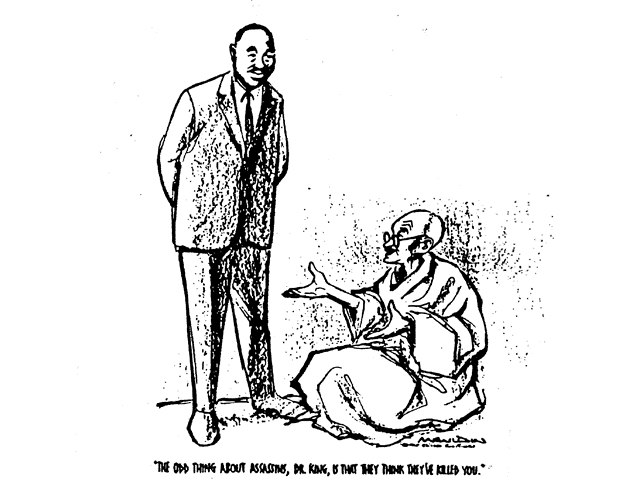

Nandy believes that Gandhi is an inevitability in today’s global political climate due to the rise of fascist groups and ideologies such as Hindutva, and he derives his certainty of this fact from various pieces of literature. Yet, he failed to address the biggest threat that Gandhian thought and action faces today, which is appropriation by the very forces that it stands against; the school of thought that took his life. Nandy says that Gandhi’s death is a statement of his life, one where he challenged the status quo and angered those who did not believe in his philosophies. There were six attempts to assassinate Gandhi, the first one led by the RSS owing to the Gandhi’s stance on untouchability in the prime of his leadership. The last and final attempt by Nathuram Godse was also planned by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and the RSS, and this came at a time where Gandhi was suffering and was awaiting death. Hence, Nandy says, his assassination came as a kind of seduction to his end, which is why he accepted his fate. Lastly, Nandy refers to the comic below to drive home the fact that assassins may have killed Gandhi and other Gandhis, but Gandhian thoughts, ideas, and actions will live on forever.

“The odd thing about assassins, Dr. King, is that they think they’ve killed you.” Source: Asia Society

Is Gandhian action really possible today?

Nandy mentions that Savarkar accused Gandhi of three crimes — of being anti-scientific, superstitious, and for not reading the works of modern Western political theory. A Gandhian defence to this would be (as put forth by Dr. Hemlata Bagla and Dr. Pradeep Sharma at the Symposium) that Gandhi was not against science; rather, he was a supporter of the scientific method and applied it in his own experiments with society and truth. He was not against technology, but was against its capitalist tendencies as well as an increase in dependency on technology to the extent that one begins to neglect the wonders of the human body. It is true, however, that Gandhi was not a fan of medical sciences. Yet, Dr. Milind Watwe says that like all other ideologies and theories, we must evolve Gandhian thought to fit the context of current realities as well. Furthermore, as Nandy points out, Gandhi was constantly reading Western scholars, albeit those with dissenting views like Tolstoy, Ruskin, and Thoreau, unlike Savarkar who was consuming the works in the mainstream, which were at the time dominated by ideas and thoughts that would later lead to Nazism and fascism.

Gandhi’s critique of Western science was placed in a larger context of the decolonization project, where he believed that the popularization of scientific knowledge must be a collaborative effort rather than a linear conveyance of knowledge from experts to the common man. His resistance to science came mostly out of his association of the subject with capitalism and colonialism. Contrarily, today’s Indian education system emphasizes a strong focus on research and development in STEM, with more and more Indian graduates entering and dominating the domestic and international workforce in this sphere. The past decade has seen a rapid increase in scientific development in the country, especially by part of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). Yet, it seems that in the quest for technological perfection, funding and support for research and development in STEM has come at a large cost from the social science sector. In 2017, the Centre drastically cut funding for PhD and MPhil seats by almost 80% in premier social science research institutes like Jawaharlal Nehru University. Currently, the Ministry of Human Resource Development is in the process of creating a National Research Foundation which aims to encourage multidisciplinary research in the country. For this, too, the initial focus areas have been reported to be nanotechnology, information and communication technology, and oceanography.

It is important to note that while India holds STEM to a very high standard, there is still a decline in the scientific temper in the country in a way that may find a sliver of congruence with Gandhian thought, in that science is generically viewed as something that should be restricted to its own sphere and practiced by trained professionals, whereas personal and public life can be lived without it. For Gandhi, this meant the evolution of the individual to be more at one with nature and to live life the way our ancestors did, and the revival of ‘alternate’ or indigenous sciences like ayurveda. In contemporary India, despite government support for STEM, there is a mass movement by political and religious groups that supports and propagates non-scientific practices and superstitious thought. This includes a rhetoric that allocates a higher scientific value to ayurveda and yoga over allopathic and Western wellness practices, such as Sadhvi Pragya Thakur’s claim to have been ‘cured’ of cancer by drinking cow urine.

Political leaders like Thakur, at various junctions, have undermined the role of science in public and private life and have reflected this in action as well. Another example would be a recent ceremony in Madhya Pradesh where a marriage between two frogs was publicly conducted to appease rain gods, and once the rain arrived and turned into destructive flooding, the frogs were divorced too. All of this was conducted under the supervision of elected officials who refuse to take accountability for their inability to curb extreme droughts and floods across the country. It seems unlikely that Gandhi would support this kind of showcase.

Experts and critics believe that this strong inclination of educationists towards technology will reduce the critical thinking aspect of humanities research, turning it into a system of set analogies and shifting its foundation entirely. More than this, it seems that the propagation of scientific education is being carried out with the intention of dissuading the youth from joining the humanities and being exposed to alternative perspectives in social and cultural issues. Today, even though STEM is an accessible field to most intersections in India, there is a still stark knowledge gap between social and technological development as STEM students are cut away from the social sciences and are discouraged to dabble in them in a nuanced manner. Furthermore, the underfunding of research in the humanities will widen this gap as it will make the social sciences less accessible to underrepresented and underprivileged voices.

Gandhi would not be pleased with this, as his major discontent with Western science was the fact that scientific discoveries did not improve people’s ‘moral sense’ and were unable to reduce injustice and inequality in modern Europe. While Gandhi’s insistence of viewing this dilemma as a binary of science and morality is highly questionable, especially for a moral sceptic like me, it is worth noting that this idea of moral policing is one that has been constant in the country’s approach to polity, even by those on the centre-left of the spectrum. Especially in today’s era of hypernationalism, this is reflected in more stringent control that is coloured with communal (and arguably savarna) undertones, where self-proclaimed vigilantes, with the tacit support of elected officials, seem to be dictating what people can and cannot do in their personal lives; this includes policing their dietary preferences, their sexual and marital choices, and their ability to move, think, and express freely. In the garb of this ‘morality’, humanity is being made to take a back seat.

This brings me to my main point: it is impossible to ignore that the Hindutva-motivated and RSS-backed Modi government constantly appropriates Gandhi to suit their own agenda. Not only have they used Gandhi’s iconic spectacles as the logo for their Swachh Bharat campaign, but have also taken his idea of swadeshi and morphed it to the capital-driven Make in India policy. At the recent inauguration of the Gandhi Solar Park at the UN Headquarters, Modi said, “Gandhiji had stressed on the real strength of democracy. He taught people to be self-sufficient and not to depend on governments.” This comes as an easy scapegoat for Modi, who ironically based an entire leg of his election campaign on being India’s chowkidar or watchman, and whose government is constantly being called out for its incompetence and lies, even though it keeps increasing its own powers.

With respect to economic inequity, experts at the Symposium had a common consensus that Gandhi’s conception of gram swaraj is the way forward for the agrarian crisis. Furthermore, Dr. Vibhuti Patel opined that the knowledge economy is in dire need of Gandhian ethics, because trafficking, child labour, and bonded labour are still evils that are prevalent today. Collective bargaining and trade unions are disappearing, and labour relations as a whole are being reinvented. In this case, Gandhian distributive justice comes as a viable solution, especially since women, the “last colony”, are still being exploited as both, public and private labour.

On the topic of nationalism, according to Lord Bhikhu Parekh, Gandhi was against the modern nation-state but not against nationalism. His definition of nationalism was characterized by a sense of community, mutual responsibility, and a resistance to foreign things. Parekh further says that the Ram Rajya that Gandhi envisioned was not one with Ram, the God, at its helm as a religious overlord; rather it was one that invoked the characteristics of goodness and righteousness that Ram stood for. Today, someone who has not been exposed to Gandhian literature would assume that Ram Rajya is a Hindutva concept, due to the imposition of North Indian religious tradition in public discourse as well as the constant and roaring demand for the building of the much-disputed Ram temple in Ayodhya. The ideas of nationalism being propagated by Hindutva forces in the country do draw a few similarities with those outlined in Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj — asserting nationhood, a unified Indian territory and language, a singular economy — but the politics of the ruling party are completely devoid of any recognition of secularism, resistance, and do not entertain non-cooperation, which were essential components of Gandhi’s conception of national identity and the road to achieving nationhood. Rather, dissenting journalists are being arrested, and the term secularism has become synonymous with anti-nationalism.

Source: Twitter

Perhaps the most controversial element today is the fact that US President Donald Trump recently dubbed Modi the “Father of India”, a title held by Gandhi in all public discourse in post-colonial India. While this statement fueled a lot of trolling by Indians on social media, who have created jokes and memes like the picture above, it has also incited Union Minister Jitendra Singh to quip that those who are not proud of Trump’s acknowledgment of Modi as India’s father cannot consider themselves to be Indian at all. A non-resident Indian named Ramesh Modi who attended the Howdy Modi event in Houston dressed as Gandhi, said that Modi and Gandhi are the same person, and described both to be “saints” and “fakirs”. According to Dr. Apoorvanand, Gandhi was the most “cultured” figure because he grappled with difficult questions, looked for answers, and spoke about these matters simply. On the other hand, Modi has not once answered any critical questions directly, and his words and responses are more reflective of denial and pushing his own accomplishments and grandeur rather than dealing with concerns with honesty and sincerity. Case in point, telling an NRI audience that “everything is fine” in India despite the fragile state of the country’s economy, reports of gross human rights violations in Kashmir, increased unemployment rates, and a rise in brutality against women and minorities.

The relevance of Gandhi’s legacy today is not as much about his person as it is about his thought and action, but the current scenario is one where this thought and action are being stifled under the garb of idolizing his person. Gandhi was always wary of extremism as he believed that if self-rule (swaraj) were to be coerced through extremist methods, “English rule will vanish but Englishness will prevail”.

Other experts at the Symposium had Gandhian (and, dare I say Utopian) solutions to this problem. Ashok Vajpayee believes that in the midst of so much noise and talk about victory and greatness by the ruling party, one must remember Gandhi’s maun vrat (vow of silence) and remain quiet. Mallika Sarabhai, who believes that “Gandhiji has been taken away from Gandhiji”, called for people to remember the Gandhian spirit of inquiry, to ask questions, and to search for the truth. Dr. Ganesh Devy drove home the point that Gandhi is definitely possible today if at every step of the way we ask ourselves, “but why?” Yet, when I asked the panel for a practical way to create a mass movement of counter-culture amidst the current domination of propaganda and divisive narratives, they had no answer. Neither were they able to provide any solution to the very real issue of multilayered brainwashing that has even seeped into the minds of caste and religious minorities. Akanksha Mansukhani, a humanities graduate and an attendee at the Symposium, rightly remarked that for most of the speakers, the dais seemed to work as a place where they foremostly expressed their concerns and discontents with the current administration, while Gandhi came in as an afterthought.

Therefore, I believe that even when the inevitable Gandhi emerges today, it will be extremely difficult for such a figure to exist as a counter-image to the current leadership, which has built its stronghold on the unofficial tenets of appropriating Gandhian principles, sidelining those who truly practice them in action, and controlling the media to such an extent that these moves are reported and advertised to the public as positive. Yet, Modi will never be perceived as an anti-Gandhian force, even with his explicit link with the RSS, whom Gandhi vehemently opposed.

While Nandy’s argument of a prophetic Gandhi rising and creating a space in the public sphere holds due relevance, I am uncertain of how successful such an individual can be, given how difficult it is for opposing voices to be given a serious platform in the country nowadays, by leaders and the public alike. These days, anything anti-establishment is considered to be anti-national, while ideas that are far from Gandhian are being given copious amounts of mileage and legitimacy, masquerading as “traditional” or “cultural” practices, with false connections being made between these and Gandhi so as not to lose out on mass appeal.

No novel by Tagore or anyone else could foresee a reality where elected officials would be appropriating Gandhi’s characteristics to further their disruptive propaganda, and while the world needs more Gandhis to save itself from the rising threats of ethno-nationalism, it also seems like it does not have the space to accommodate such a personality. Right now, more aggressive action such as that of environmental activist Greta Thunberg is what is speaking more effectively to the masses. Thunberg’s movement is still one that is deeply embedded in a belief in resistance and protest; yet, the tone by which the message is being driven is angry and frustrated, more reflective of sentiment than a disciplined ability to control it. It is this tone that is resonating with the people today, as more passive approaches to dissent have proven to fall on deaf ears among most leaders, especially in those in the right-wing.

Nandy and the other esteemed figures at the Symposium are not wrong in idolizing Gandhian principles and hoping that a similar personality will certainly come to the forefront very soon. Mahatma Gandhi is undoubtedly possible, but is it practical? The analysis given by the scholars on the panels, for me, left a reasonable gap in being able to provide steps for the practical implementation of Gandhian thought and action in today’s political climate.

Hence, while Gandhi’s belief in nonviolence and his search for truth and distributive justice will never, ever be irrelevant, perhaps the only realistic way to preserve certain elements of Gandhian thought and to keep the ‘Mahatma’ alive is to recognize that today’s neocolonial powers have been raised with the same Gandhian values in the background (and in India, the foreground) throughout their lives, and have still made a conscious choice to break away from this tradition in their quest for economic and political power. They have, with clear bias, picked the aspects of Gandhi’s ideas that fit in most conveniently with theirs, and continue to present this as their way of preserving “Indian culture”. It is, therefore, necessary to seriously alter Gandhian action to make it more relevant, and a tad bit more radical, to effectively disrupt these overarching powers and reassert the importance of truth and self-rule among the people.

References

BJP Minister Gets 2 Frogs Married to Make it Rain in MP, Draws Oppn Flak. (2019). Retrieved 27 September 2019, from http://news18.com/news/india/madhya-pradesh-minister-organises-frog-wedding-to-please-rain-gods-draws-oppn-flak-1788533.html

Desk, W. (2019). Modi and Gandhi are same, says NRI dressed up as Mahatma Gandhi. Retrieved 27 September 2019, from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/modi-and-gandhi-are-same-says-nri-dressed-up-as-mahatma-gandhi-1602035-2019-09-22

Guha, R. (2006). GANDHI AND SCIENCE, The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 October 2019, from http://ramachandraguha.in/archives/gandhi-and-science-the-telegraph.html

Prasad, S. (2019). Towards an understanding of Gandhi's views on Science | Articles - On and By Gandhi. Retrieved 1 October 2019, from https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/views_on_sci.htm

Rai, S. (2019). Nation and Nationalism: Revisiting Gandhi and Tagore | Articles - On and By Gandhi. Retrieved 27 September 2019, from https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/nation-and-nationalism-revisiting-Gandhi-Tagore.html

Suhrud, T., & De Souza, P. (2010). Speaking of Gandhi’s Death. Delhi: Orient Black Swan.

Details of the Symposium and its panelists can be found here.

Original image by Hana Masood. Artwork by Tyler Street Art