While Ukrainians have been facing the brunt of Russia’s military onslaught, the effects of the conflict are not just limited to the region. Apart from pounding Ukrainian cities to rubble, Russian fighter jets and tanks have sent shockwaves across the world.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) states that the entire global economy will be impacted by the ripple effects of the war through three main channels: higher inflation levels, disruption of supply chains, and reduced business confidence. In fact, food, fuel, and energy prices have hit record highs due to reverberations in global supply chains. The disruption of Russian energy exports has led to countries like Qatar re-routing some of its energy supplies bound for Asia to Europe and war has forced Ukraine to shut down many of its ports, thereby preventing its agricultural exports from leaving its waters.

The biggest impact of the war will most likely be on food security, as both Russia and Ukraine are among the biggest players in the global agricultural sector.

Why are Russia and Ukraine crucial to global food security?

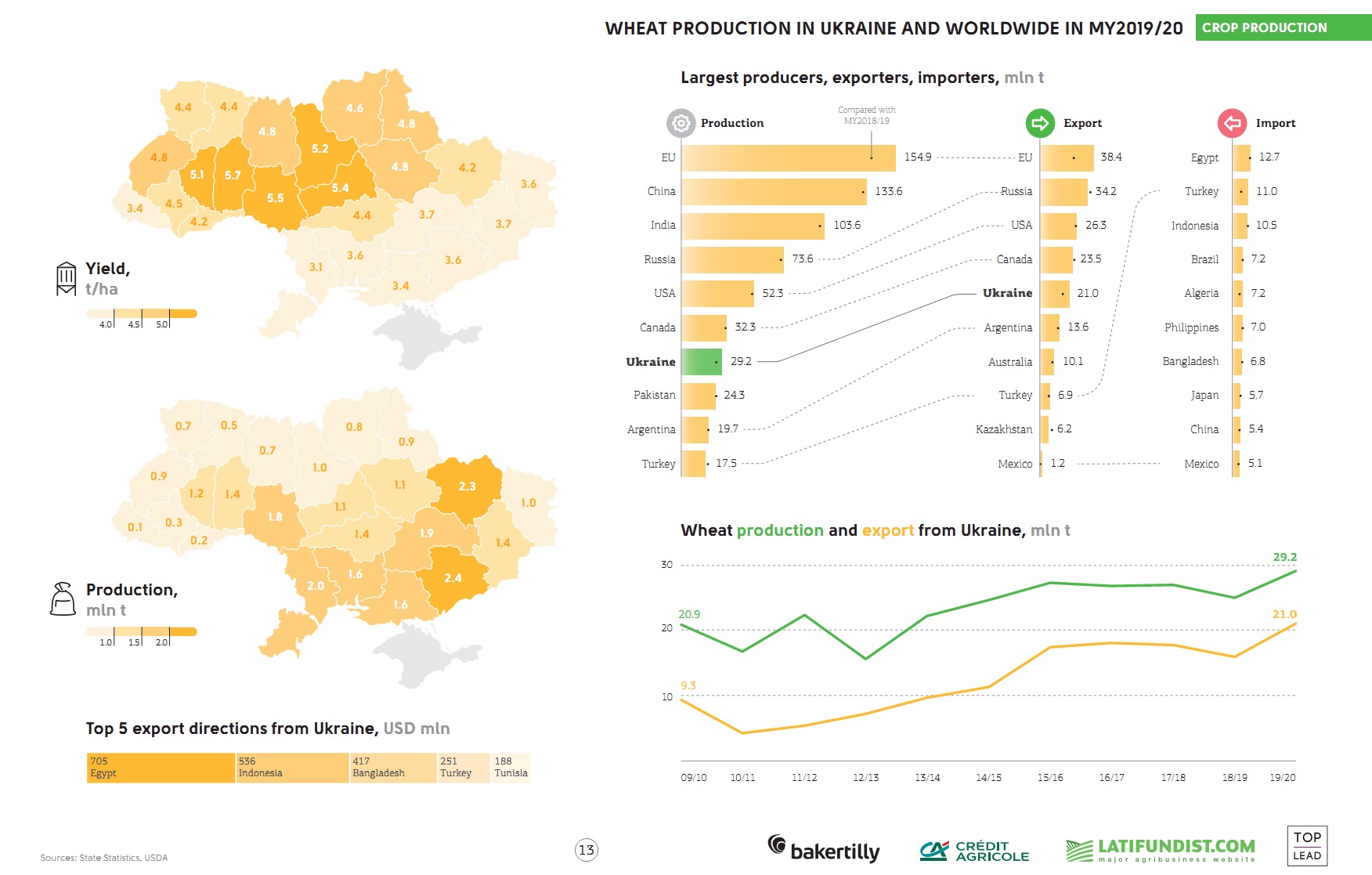

Together, Russia and Ukraine account for around 14% of the total wheat production, which is nearly the size of the European Union’s (EU) total wheat production. Russia is the largest wheat exporting country, accounting for 35 million metric tonnes of wheat exports in 2021-2022, while Ukraine’s wheat exports during the same period were around 24.2 million metric tonnes, the third-largest in the world. Combined, their exports are more than that of the entire EU.

Both countries are significant producers and exporters of maize, barley, sunflower oil, and soybeans. Furthermore, Russia is the world’s largest exporter of fertiliser materials, including minerals and chemicals like nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium, with an export value of $7 billion in 2020.

The conflict has already forced Ukrainian farmers to halt production and leave farmlands. Moreover, Western sanctions on Russia, especially the removal of Russian banks from the SWIFT financial network, have made it extremely difficult for Moscow to conduct trading activities. Against this backdrop, there are bound to be supply disruptions across the global food supply chain, which will inevitably lead to rampant food shortages, rising demand for basic food items, and increasing food prices.

For instance, Lebanon imports almost 87% of its wheat from Ukraine and a sudden halt in supplies has resulted in a shortage of bread, which in turn has led to a rise in the demand and price of bread. Yemen is another country that will be severely affected by the war. In fact, the World Food Programme (WFP) has warned that war in Ukraine could double food prices, further exacerbating the already spiralling humanitarian crisis. Similarly, the agricultural industries of many countries in Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East face an uncertain future.

Will fighting in Eastern Europe impact India’s agricultural sector?

India depends on Russia and Ukraine for the supply of several key agricultural commodities, and a combination of war and sanctions on Russia could prove to be more than a headache for the Indian agricultural sector. In fact, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has said that the government is worried that the disruptions caused by the war will have far-reaching consequences on India’s farming sector.

Around 11% of India’s total fertiliser imports come from Russia and Ukraine. Russia alone supplies more than 17% of India’s potash imports and 60% of its imports of NPK (Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium)—key components in fertilisers. Therefore, a shortage of fertiliser components could disrupt the production of crops and farmers’ streams of income. Additionally, a lack of availability of potash and NPK would lead to a significant increase in input costs and ultimately result in higher food prices for customers. Since the fertiliser industry is heavily subsidised, supply disruptions would force the government to increase subsidies and take more protectionist measures, a move that could lead the government to increase taxes to raise funds.

In order to avoid such a situation, India has been scrambling to secure additional fertiliser supplies from Morocco, Israel, and Canada. Earlier this week, India’s top potash manufacturer, India Potash Ltd, signed a deal with an Israeli fertiliser company for over 600,000 tonnes of potash for the next five years.

#India's agriculture sector is expected to face the heat from hostilities between #Russia and #Ukraine which are expected to push up prices and availability of -- Potash -- a key component used in the manufacturing of fertilisers.#RussianUkrainianWar pic.twitter.com/ADmrl2hycQ

— IANS (@ians_india) March 4, 2022

Another casualty of the Ukraine conflict is the edible oil industry. Demand for edible oils in India is very high and domestic production has not been able to maintain the pace with rising consumer needs. As a result, India has been importing more than half of its edible oils, which are mostly used in food and health products. For instance, India receives 90% of its sunflower oil supplies from Russia and Ukraine. Therefore, delays caused by the war will almost certainly lead to drastic shortages of a widely-used product. Since Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, the price of cooking oils, including sunflower oil, has continued to surge in India, and industry experts warn that a protracted war would wreak havoc in the industry.

India signed a deal with Russia for discounted crude oil supplies in order to hedge against rising oil prices. Can a similar arrangement be made in the agricultural field?

Recently, India announced that it would purchase crude oil from Russia at a discounted rate in order to bring down surging prices. However, the possibility of a similar deal in which India continues to purchase agricultural products from Russia is unlikely.

In the case of the oil deal, India will have no option but to trade with Russia in local currencies, as the United States has barred Moscow from trading in dollars. India and Russia, therefore, have set up a Rupee-Ruble trade arrangement in order to finalise the sale and purchase of crude oil. Additionally, since several European countries including Germany have not stopped Russian energy imports, Russian banks dealing in payments for energy have not yet been excluded from the SWIFT network. As a result, Moscow will be able to trade in energy without a lot of hassles.

Since other Russian banks have been excluded from SWIFT, trading in agricultural products will prove difficult for both Moscow and New Delhi. Furthermore, the volatility of the Ruble would make it difficult to implement another Rupee-Ruble payment mechanism. If the Ruble continues to plummet, its value will erode and render Indian payments for Russian imports essentially worthless.

Does the war present the Indian agricultural sector with any opportunities?

As mentioned earlier, the war has severely affected the ability of Russia and Ukraine to export wheat and this void has opened an opportunity for India. Major wheat importing countries like Egypt, Israel, Oman, Nigeria, and South Africa, which have traditionally relied on Russian or Ukrainian wheat imports, have now approached India for wheat supplies. While India accounts for 14% of the global wheat production, on par with Russia and Ukraine combined, its share in the world market is only 3%, since most of India’s wheat is used for domestic purposes. Given that Indian wheat stocks are three times the mandatory limit of 7.6 million tonnes, New Delhi can easily afford to fill the gap left by Kyiv and Moscow.

India is looking at exporting nearly 10 mt wheat in FY23 to bridge the supply gaps arising from the Russia-Ukraine conflict.Russia and Ukraine export nearly one-third of global wheat every year.

— ADFC Futures/Forex (@ADFCFUTUREFOREX) March 20, 2022

cont...#wheat #grains #agriculture #food #india #russia #ukraine #RussiaUkraine pic.twitter.com/xRCJ0FrvuI

Finally, a long-drawn conflict between Russia and Ukraine would not only disrupt global agricultural supply chains and trade but also worsen the current economic woes caused as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the global surge in inflation levels. Against this backdrop, it is crucial that India take adequate steps to reduce the impact of the conflict in Ukraine on its agricultural sector, including by seeking additional import options and tapping into export markets.