Over the past seven years, China has made colossal investments as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in various infrastructure projects in developing economies to boost trade and growth. However, the inability of partnering countries to pay back these monumental debts has drawn into question whether China will be able to recoup its significant investments. These suspicions have only been amplified by the coronavirus pandemic, which has further impoverished already heavily indebted countries. Given these developments, recent reports reveal that China will begin to ‘slow down’ its international engagements in the coming years. Against this backdrop, it becomes crucial to ask whether the BRI has truly achieved its purpose of expanding China’s sphere of influence and challenging US hegemony.

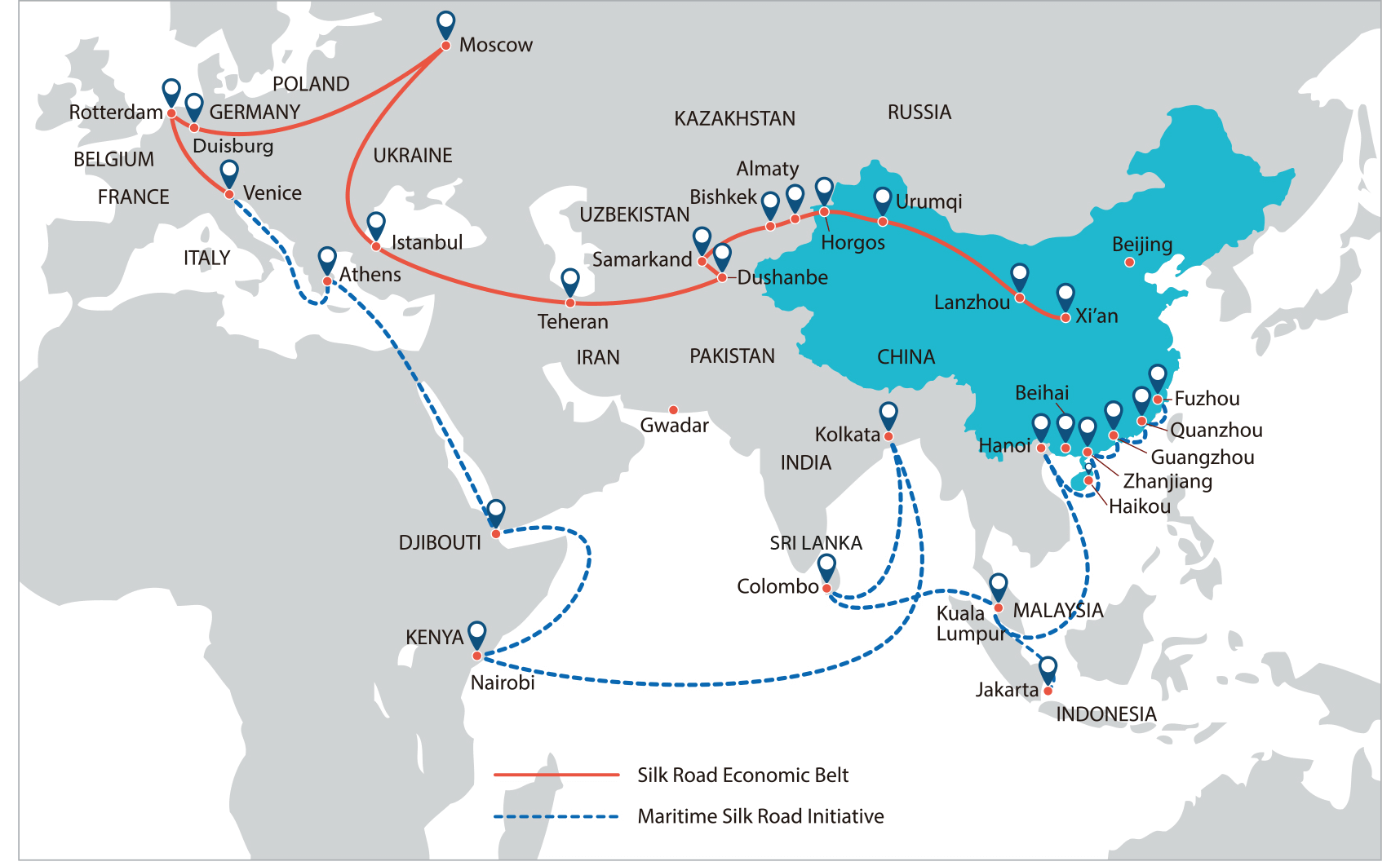

The original vision of the BRI was to build six corridors of land and maritime networks to improve regional integration, foster new investment opportunities, increase trade, and stimulate economic growth. Additionally, a relatively unspoken but understood aim of the project was to project a more assertive China and to serve a blow to the US’ “Pivot to Asia”.

The initiative now connects more than 167 countries and organizations through 198 cooperation documents, with a focus on Asia, Europe, and Africa; there are also emerging projects in Latin America. This has allowed China to establish secure energy transport routes, guarding against American-installed hurdles and piracy. Previously, up to 80% of Chinese energy imports came in through the Malacca Strait, which left its vessels susceptible to pirate attacks. Now, via pipelines that run through Myanmar and Central Asia, China has secured 40% of its gas needs, thus cementing its energy security.

Simultaneously, the Trump administration has shown a marked disinterest in multilateralism, undoing many of the gains made under the Bush and Obama administrations, wherein the US gained a stronger footing in Central Asia. However, Trump’s isolationism, exemplified by his disdain for international organisations and multilateral trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), has left a sizeable vacuum for China to exploit. Even though the Trump administration has attempted to compensate for this through the BUILD Act, which boasts a $60 billion international investment portfolio, it pales in comparison to China’s investments, which could reach $1.3 trillion in another six years. Furthermore, given the volatile situations in many of the countries China is partnering with, Beijing has also taken a keen interest in expanding diplomatic and strategic ties.

In Central Asia, this has paved the way for China to become the region’s top investor. Moreover, the construction of new railway lines and roadways provides enhanced connectivity to European markets, illustrated by the fact that trains from China to Germany are now able to deliver goods in 12 days, compared to 40 days by sea. Along these same lines, China is using the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to link Kashgar in the Xinjiang province with the coastal city of Gwadar in Baluchistan; once the project is completed, China will have continental access to the Indian Ocean.

China has also used this opportunity to build entirely new markets and invest in relatively untapped and resource-rich economies in Africa. The continent has a huge infrastructure deficit, lacking reliable power, water, and roads, providing a seemingly unending number of projects for China to invest in and build from the ground up. Between 2000 and 2015, Chinese companies registered over 1,000 African manufacturing proposals for glass, recycled steel, ceramics, textiles, dyeing, tanneries and shoe factories, among many other ventures. This has also generated many new jobs for locals.

This has also allowed China to challenge US hegemony and project an image of a benevolent superpower. By buying up the debt of middle-income countries like Ethiopia and Kenya and offering large commercial loans to countries with “high default or sovereign risks” like Argentina, Ecuador, and Angola, China has been able to carve out competing spheres of influence. Between 2000 and 2014, Chinese investment in Africa went from 2% of US levels to 55%. At this pace, Chinese investments in most key areas are expected to surpass US investments within the next decade.

All of this has given China an immovable presence in BRI partner countries through a practice that is called “debt-trap diplomacy”. Having loaned upwards of $160 billion to African countries, it is estimated that around 20% of African government debt is now owed to China, forcibly extending their dependency on Beijing. Moreover, this phenomenon is not unique to Africa. According to the New York-based consultancy Rhodium Group, at least 18 recipient countries are renegotiating their debts with China, with 12 others still in talks to restructure an estimated $28 billion of Chinese loans. Aside from the rapidly increasing debt, this has also forced several countries to surrender their control over crucial resources and strategic locations, eroding their sovereignty over their own territory.

For example, in a debt swap to China in 2017, Sri Lanka ceded control over its strategic Hambantota port on a 99-year lease. In Laos, in return for helping build dams across the Mekong mainstream, Beijing took over the country’s electric supply. Likewise, Zambia’s copper industry is now under the control of Chinese companies, a sector that accounts for 70% of the country’s export revenues. Similarly, through investments in Djibouti, China has been able to station an active military base at the biggest and deepest strategic outpost of Doraleh in the Horn of Africa, giving it strategic access to the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf.

In terms of boosting its own earnings, in 2019, China has earned $1.34 trillion, outpacing the country’s aggregate trade growth by 7.4%. Further, having close to maxed out its manufacturing capabilities due to mounting environmental issues and saturated export growth, the BRI has been successful in providing new export markets and manufacturing hubs.

However, despite all these successes, not everything has come up roses for China. The sacrifices of doing business with China is now dawning in several countries, who are now realising what they believe to be the true motives of these sizable loans. Local production in many of these countries has suffered a huge blow, as lucrative contracts are being reserved for Chinese companies.

At the same time, the ongoing pandemic has left many of these countries unable to repay their debt, with several calling for a debt freeze or complete cancellation. China, for its part, has offered some debt relief to these countries. Beijing has previously cancelled $160 million in debt owed by Sudan in 2017 and $78 million owed by Cameroon in 2018. It also announced the suspension of debt repayments for 77 low-income and developing countries, signalling China’s commitment to the G-20 debt relief program. Due to these developments, China is growing increasingly convinced that it will not be able to recoup its investments and will thus try to cut its losses by slowing down its international engagements. A report by European financial services company Allianz predicts that Beijing’s “role as a global growth driver” will “recede in the coming years”.

Nevertheless, the BRI has already yielded several tangible and invaluable rewards to China in the form of trade, strategic, and diplomatic ties, and allowed it to challenge US dominance on a global scale. China has undeniably suffered a significant financial blow as a result of the ongoing pandemic. Allianz forecasts that Beijing’s GDP growth is likely to hover between 3.8% and 4.9% over the next decade, after averaging 7.6% during the 2010s. Partnered with a rising domestic debt burden, there is a fear that China may have bitten off more than it can chew with the BRI. However, despite this, and mounting suspicion regarding its underlying motives, the BRI has already successfully laid a long-lasting foundation for greater connectivity both on land and across the high seas and enabled access to crucial resources and strategic locations. However, for the initiative to remain prosperous, Beijing must be more judicious in choosing partners who are more likely to be able to pay off their debt in order to simultaneously pursue its goals of expanding its sphere of influence while still addressing its domestic debt concerns. Else, it leaves the door open for the US to reassume its position as the world’s only superpower.

Has China Succeeded in Achieving the Objectives of the BRI?

BRI investments have dried up due to the COVID-19 pandemic and will continue to decline. Has China achieved what it set out to do?

December 16, 2020

SOURCE: HERBERT SMITH FREEHILLS