In 2006, a survey conducted by the political scientist, Yogendra Yadav and Centre for the study of Developing Societies (CSDS), found that, “of the 315 key decision-makers surveyed from 37 Delhi-based (Hindi and English) publications and television channels, almost 90% of decision makers in the English language print media and 79% in television were from the ‘upper castes’.” The upper castes constitute about 24% of India’s population while their share among key media personnel amounts to a staggering 88%. On the other hand, the Dalit community with a population of 16.6 % (201 million) has a 0% representation at the policy-making level in media organizations.

The National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) data suggests crime rate against Dalits rose by 25% in a decade from 2006 to 2016 and the cases pending police investigation for crimes against Dalits has risen by 99%. While crimes against Dalits, ranging from social discrimination to extreme forms of violence have been ever increasing, there has been no significant corresponding increase in media’s space to these stories. On the other hand, the fact that 16.6% of India’s population has representation equivalent to none in India’s mainstream media indicates a deeper marginalization of the Dalit community and the inaccessibility of the top elite media organizations to the masses of the country.

This article attempts to analyze the interplaying elements of caste and class privilege at the core of Indian Journalism, creation of upper caste dominance at editorial positions and why it is necessary to break this hegemony for a clearer reflection of the social setting of India.

Factors influencing the number of Dalit Journalists

A mere discussion among the journalists in an upper caste dominated newsroom was first prompted by an article written by BN Uniyal, ‘In search of a Dalit Journalist’, for The Pioneer. Over the years, this sudden realization was followed by a number of editorial pieces and research articles on the absence of Dalit journalists in Indian media, the most recent one being Ajaz Ashraf’s research article in The Hoot based on the interviews with more than 21 Dalit journalists. “After searching the country for more than 10 years, I have been able to find eight Dalit journalists in the English media. Only two of them have risked "coming out", writes Sudipto Mondal. An assessment of these primary accounts broadly suggests a number of causes that compel many of the Dalit journalists, already less in number, to quit journalism. These causes emanate from the deeply entrenched humiliation, discrimination by those who enjoy the social capital of Indian society, that is, caste along with class privilege.

1. Journalism, over the years, has become a full-time profession which demands rigorous practical and academic training. This along with technological development and economic liberalization has contributed to the formation of a ‘media industry’. This huge mainstream media industry that prioritizes business over everything rest has become too sophisticated for the masses with the domination of upper castes that have enjoyed the caste and class privilege for generations and have owned the entire media. The mainstream media has practised ‘untouchability’ in its truest sense that in the vision of the majority rural or urban lower caste and class people, here Dalit community, do not even see journalism as a viable career for them.

Even in the 21st century modern India, the effect of every development in media has ironically taken us back to the period when the profession of reading and writing (journalism) still remains an upper caste thing to do. No outright ‘untouchability’, but yes, practically ‘untouchability’.

2. Among those Dalit students, who aspire to become a journalist, some lack the awareness regarding journalism courses, colleges or access to the social circle that could provide them with the necessary information. And a majority of them who have the necessary information do not end up taking admission due to the high fee structure, the economic burden of shifting to other city and the following expenditure. A number of educational institutes in India provide journalism courses and provide scholarship to students belonging to the Schedule Castes, including some private institutions. These scholarships resulted in driving a number of Dalit students to journalism classrooms and have passed out from these colleges. Passing out is just one step that leads them to the road of the struggle of access for recruitment, the ensuing stigmatization and the need to conceal their identity from time to time.

3. A number of reports based on primary interviews suggest, since the non-Dalits dominate the media houses in most of the cases, their callous attitude, entrenched preconceived notions and stigma towards Dalits staunchly reflect in their recruitment process of journalism jobs and even in their conversations regarding caste issues. It is a prevalent stigma among the editors that Dalits do not know English and are not good enough in writing and hence cannot get into English journalism. To this, Sudipto Mondal argues, “It is not like Dalits and Adivasis are unable to break into English journalism because they can't speak English or because they make bad journalists. An audit of the raw copies filed by reporters of English newspapers should bear out the fact that most reporters can't string together a decent sentence in English.”

There are journalists who have shared their experiences right from outright caste discrimination in the newsrooms and also during placements at colleges and have emphasized how important it was to have a specific social circle or networks to gain access to the big media houses. The social privilege of the rich and the upper castes already made it easier for them to use connections, get contacts and get into media organizations. Ajaz Ashraf sums it up well since the social groups and networks define the dominant and urban culture, Dalits with a different background get sifted out. Media outlet representatives who visit the campus have a subconscious bias for those who speak their lingo, share their dressing style and, crucially their worldview. Students, therefore, become victims of that incorrigible human tendency of people preferring to bond with those sharing the same culture.

4. As Ravish Kumar says, “If everyone makes it the newsroom based only on merit and chance, then surely some Dalits should also have made it.” A very few of them take up journalism jobs after completing required journalism courses and those who continue working as a journalist often quit after some years and pursue their career in some other sector. Out of the 21 Dalit journalists that Ajaz Ashraf interviewed, 12 of them have left journalism and have taken up government jobs. One of the significant reasons for this is that their weak economic base makes them fear job insecurity which is a defining characteristic of the private sector.

Working at a low salary without any scope of promotion for years adds to their disenchantment with journalism jobs. In a way, their aspirations of bringing about a change for their community are shattered by the real world of ‘corporatized journalism’. Those who have the class privilege, if not caste, can manage to survive in the media industry. The ones who do not enjoy either of them finally end up quitting journalism.

They are majorly the first generation youngsters from a majority of Dalit families, rural and urban, who aspired for and have gone through various social and economic struggles to enter into that newsroom and ensure that they belong. However, eventually, they become a victim of this systemic development which periodically ensures that social capital in terms of identity (caste) coupled with economic stability (class) overpowers everything else in and about an individual.

The Need for Mainstream Inclusivity

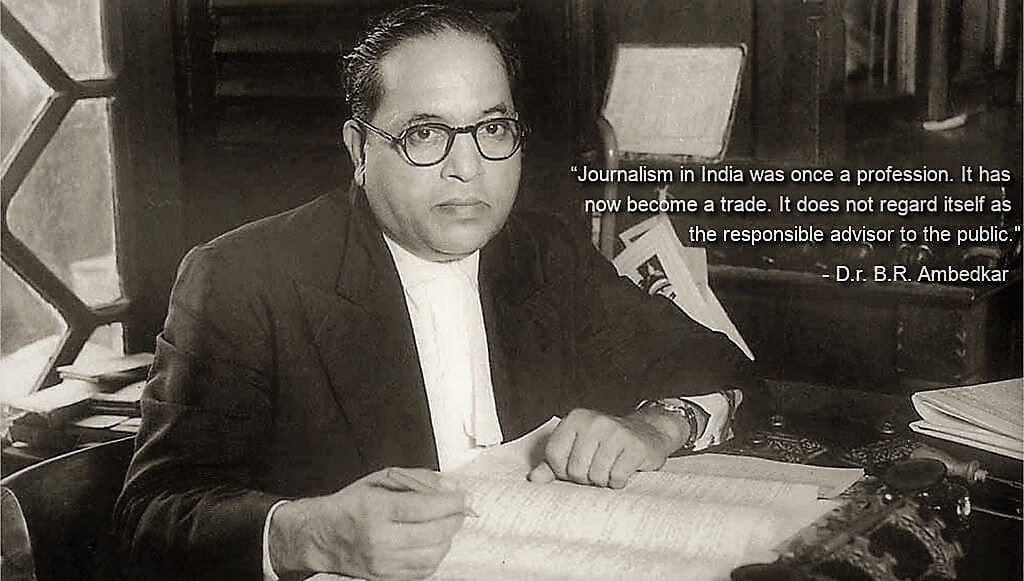

The marginalization of Dalits in media is not a new concept in Indian journalism. It has existed right from the pre-independence period when Kesari newspaper refused to publish the advertisement about Dr Ambedkar’s newspaper, Mook Nayak. The Indian media that praise Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi for starting a newspaper, Harijan, for the untouchables, never address Dr B.R Ambedkar's labours that are responsible for running four newspapers for his people. Let us take a very recent example, on 7th June 2019, IndiaSpend published an extensive report on the battles of the Dalit community over reclaiming their lands, a movement that was initiated in 1941 by Ambedkar and has reached its peak in 2019 when across 13 Indian states, there are 31 conflicts involving 92,000 Dalits who are fighting to claim their land. But, there have been no timely reports, follow-ups on these struggles. There is no dearth of stories on atrocities and discrimination against Dalits ranging from manual scavenging to cooks refusing to cook for Dalit children in schools. However, there has been no bold coverage or a periodic primetime show by the majority of the mainstream media to question the deep-rooted caste consciousness in society.

A simple experiment of surfing through the internet for Dalit news stories presents us with news stories that include majorly two issues, violence and reservation. This event-based and selective coverage of media has, in the process, made the word ‘Dalit’ synonymous to violence and reservation, further stigmatizing the public perception towards the Dalit community and leading them to isolation. Today in India, the youth can be extremely sympathetic towards an international issue of injustice, to the issues of gender inequality, LGBTQ rights and every other form of discrimination, except caste discrimination in their own society. This is the plight of an incomprehensive approach and biased lens of the media ‘industry’ towards news stories that involve the Dalits. Perhaps they are too intimidated by the upper caste backlash that will follow if they explore the intrinsic caste factor in cases of atrocities.

In my interview with Randhir Kamble, a senior journalist at News18 Lokmat, he suggests that there is no such a thing called ‘Dalit journalist’ and a journalist is just a journalist. He further adds, a journalist from a Dalit community may be as insensitive as any upper caste journalist if he/she has had the class privilege and is strange to the struggles and stories of a majority of Dalits in India. However, it can be argued that the proportion of Dalit journalists in media is marginal to an extent that there can be no legitimate comparison of their approach towards certain issues, which is exactly why there is a need for inducting more Dalit journalists into mainstream media. On the other hand, when almost 90% of media belongs to the caste and class privileged ones, how can we look forward to casteless journalism in India?

Today, the Internet has become an alternative media for educated Dalits who have severe criticisms regarding mainstream media. There are a number of Dalit news websites like Round Table India, Dalit&Adivasi Students’ Portal, Khabar Lahariya social media pages and YouTube channels like Dalit Camera that provide news and information about Dalit issues and stories. But, their readership and viewership significantly confine to the Dalit population. These stories, these voices remain confined to blogging and awareness within the community itself and in extreme cases are picked up by some mainstream media.

There is a need for this impact of Dalit assertion to break the vault and enter into the mainstream media in a larger number. There is a compelling need for these stories to come to the fore and this can be ensured only when we have people from these communities working in the national media. An increase in the number of well-trained journalists from the Dalit community can eventually enable them to carve their space into senior positions at news media houses that enjoy a major share of readership/viewership and thus can have an influence over the coverage of caste-sensitive news stories. It would be an exaggeration to claim that this would end the marginalization of Dalits in media, but, would undoubtedly ensure a space for gradual inclusivity of marginalized sections.

The mainstream media journalists who claim to be the torchbearers of a progressive society need an immediate introspection of the social diversity of their own news and editorial rooms and must make efforts along with journalism institutions towards bridging this ever increasing gap of isolation. Inclusion of Dalits in media is not just about seeking reservation in the media industry but to strike at the very core of those premeditated or non-premeditated and non-outright factors of caste and class privilege that result in the social exclusion of educated and capable Dalit journalists to reach the top policy-making positions in the mainstream media. Until this is achieved, there is a need to keep reflecting back on the question that BN Uniyal had posed in his article, “What would journalism be like if there were as many journalists amidst us from among the Dalits as were among the Brahmins?”

References

Alam, M. (2019, March 24). Interview 'But You Don’t Look like a Dalit': Yashica Dutt on 'Coming Out as Dalit'. Retrieved from The Wire: https://thewire.in/caste/coming-out-as-dalit-yashica-dutt

Aminmattu, D. (2016, August 3). Where are the professional dalits in the media? Retrieved from Round Table India: https://roundtableindia.co.in/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=8708:where-are-the-professional-dalits-in-the-the-media&catid=119&Itemid=132

Ashraf, A. (2013, August 12). Caste on the campus. Retrieved from The Hoot: http://asu.thehoot.org/media-watch/media-practice/caste-on-the-campus-6959

Ashraf, A. (2013, August 12). Farewell to media dreams. Retrieved from The Hoot : http://asu.thehoot.org/media-watch/media-practice/farewell-to-media-dreams-6962

Ashraf, A. (2013, August 12). The untold story of Dalit journalists. Retrieved from The Hoot: http://asu.thehoot.org/media-watch/media-practice/the-untold-story-of-dalit-journalists-6956

Chandran, R. (2017, January 24). Report like a Dalit girl: one Indian publication shows how. Retrieved from Thomson Reuters: http://news.trust.org/item/20170124114722-ebqaa

Jeffery, R. (2007, May 8). [NOT] being there: Dalits and India's newspapers. Retrieved from South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies: https://sci-hub.tw/https://doi.org/10.1080/00856400108723459

Kumar, R. (n.d.). Absent Dalit: the Indian newsroom. Retrieved from India Seminar: https://india-seminar.com/2015/672/672_ravish_kumar.htm

Mallapur, A. S. (2018, April 4). Over Decade, Crime Rate Against Dalits Up 25%, Cases Pending Investigation Up 99%. Retrieved from IndiaSpend: https://www.indiaspend.com/over-a-decade-crime-rate-against-dalits-rose-by-746-746/

Mondal, S. (2017, June 2). Indian media wants Dalit news but not Dalit reporters. Retrieved from Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2017/05/indian-media-dalit-news-dalit-reporters-170523194045529.html

Rani, J. (2016, November 15). The Dalit Voice is Simply Not Heard in the Mainstream Indian Media. Retrieved from The Wire: https://thewire.in/media/caste-bias-mainstream-media

Raza, D. (2018, May 25). Meet the Dalits who are using online platforms to tell stories of their community. Retrieved from Hindustan Times: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/meet-the-dalits-who-are-using-online-platforms-to-tell-stories-of-their-community/story-nkg4lHQ1DL44DbCBiJ7CrN.html

Reporters Without Borders. (2019, May 29). Media Ownership Monitor: Who owns the media in India? Retrieved from Reporters Without Borders: https://rsf.org/en/news/media-ownership-monitor-who-owns-media-india

Shodhganga. (n.d.). Retrieved from Shodhganga: https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/135582/12/12_chapter%202.pdf

Subramani, S. K. (2014, February ). Internet as an Alternative Media for Dalits in India: Prospects and Challenges. Retrieved from IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science: http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol19-issue2/Version-5/R01925125129.pdf