The diversion of political, social, and financial resources towards COVID-19 containment efforts has negatively impacted the sexual and reproductive rights of women across the world. In turn, the pandemic has further obstructed the production, distribution, and accessibility of already disempowered family planning services. In fact, it is predicted that 46 countries will face stock shortages of at least one form of contraception over the next six months.

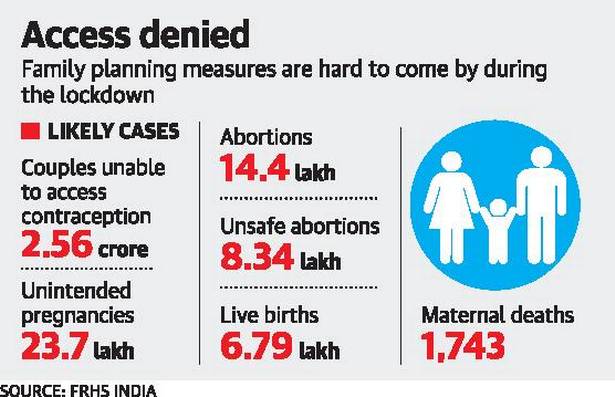

In India, clinical family planning services are only likely to once again operate at full capacity in September 2020, while the commercial sale of over-the-counter contraception is likely to resume in a phased manner by the third week of May. A policy brief by the Foundation for Reproductive Health Services estimates that, in this scenario, the pandemic would result in contraceptives becoming inaccessible to 24-27 million couples across the country, resulting in almost 2 million unintended pregnancies. Concurrently, this is expected to cause an increase in the number of unsafe abortions and maternal deaths as an increasing number of women will be restricted from availing medical services and neccessary medications due to the coronavirus-induced lockdown and the ensuing restrictions on movement.

Over the years, India has made significant improvements along several parameters of family planning, such as the total fertility rate, the infant mortality rate, and the maternal mortality rate. In addition, more and more Indian women are using modern forms of contraception, which is crucial in securing women’s autonomy and well-being. Reliance on modern contraception prevents frequent and unplanned births, thereby reducing infant mortality and maternal mortality rates. However, the inaccessibility of family planning services during the lockdown threatens to undo much of the hard-earned progress made from the decades-long efforts of Indian policymakers. Sharmala Dupte, the director of medical at the Family Planning Association of India, argues that the pandemic has pushed India 50 years behind in its efforts on family planning.

The catastrophic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on reproductive and sexual rights in India is a result of the excessive and unnecessary focus of family planning programs on female sterilisation or tubectomies. Over the years, Indian policymakers have attracted criticisms from domestic and international experts for being overreliant on female sterilisation to solve India’s population problem. The method is primarily criticised for being overly invasive and dangerous, and placing a disproportionate burden on women to propel family planning strategies. At the same time, the practitioners and camps that conduct these procedures are often criticised for failing to provide counselling prior to the operation to attain the informed consent of the women. A lack of oversight in sterilisation camps, which are promoted by the government, is an all too common occurrence. The dangers of female sterilization and the facilities used were highlighted in the 2014 Bilaspur incident, when 13 women died in a sterilisation camp due to unsanitary conditions and poor hygiene during the surgery.

Moreover, experts worry that India has invested excessively in a single form of contraception. While global statistics show a decline in women relying on female sterilisation from 20.5% to 19% from 2005 to 2015, India witnessed an increase from 34% to 36% during the same period. In fact, from 2006 to 2016, India reported a declining use of modern contraception from 48.5% to 47.8%. Despite these declines, the total fertility rate, which calculates the number of children birthed per woman, also declined from 2.7 to 2.2. While this may, at first glance, suggest that India is achieving its family planning goals, this decline is driven by the State’s aggressive and dangerous promotion of female sterilisation to curb population growth. This is proven by the fact that out of the 47.8% of women in India that use modern forms of contraception, 75% rely on female sterilisation.

The first hindrance to the sustainability of India’s sterilisation-centric family planning approach is the lack of accessibility to clinical services during the COVID-19 outbreak. According to the advisory issued by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, provision of sterilisations and IUCDs remain suspended in public facilities. For example, in Bihar, UP, and Rajasthan, three states which have comparatively higher total fertility rates and also perform poorly in other family planning indicators, authorities directed health care facilities to discontinue family planning services as medical facilities were advised to only conduct essential services. This resulted in an unprecedented and sharp decline in tubectomies. In 2019, India conducted around 3.5 million tubectomies. However, due to the discontinuation of services during the outbreak, the numbers in 2020 are predicted to decrease by 0.69 — 0.8 million. While the demand for tubectomies remains unchanged, the restrictions on the service providers caused a decline in the number of sterilisations conducted in 2020, adding to the number of unintended pregnancies caused by the pandemic.

In the absence of a comprehensive approach that focusses on education, the destigmatisation of family planning, and the use of contraception, India has become over-reliant on female sterilisation to drive its family planning policy. This policy has caused hindrances in access to other forms of contraception as well. While chemists continue to provide condoms, oral contraceptives, and emergency contraceptives even during the lockdown, the behavioural pattern of consumers is such that most buyers prefer to buy contraceptives from shops that are further away from their residences so as to maintain anonymity. Since the lockdown has restricted movement across the country, this has emerged as a significant obstacle for many couples in India, who may then engage in unprotected sex, which greatly increases the chance of pregnancy.

Further, as contraceptives are looked at with disdain by the Indian society at large, producers also face resistance from police personnel who refuse to accept them as essential goods, causing impediments in the movement of stocks to retailers and wholesalers. The supply-chain is also affected as pharmaceutical factories face disruptions to production and distribution during the lockdown. The CEO of Raymond Consumer Care, which manufactures and markets the KamaSutra brand of condoms, said that domestic market sales were down by 50% in March and 60% in April. Hence, the stigmatisation surrounding over-the-counter contraceptive adds to the woes of couples in search of contraception.

These challenges are compounded by the fact that dependence on female sterilisation for contraception requires constant intervention by and support of the government. While the reliance on sterilisation does not require continuous motivation by the government, unlike condoms or oral contraceptive pills, this creates an over-reliance on public facilities for contraception. This is because most women bank on public health sector facilities for sterilisation procedures. About 82% of the female sterilisations procedures are conducted in government or municipal hospitals, community health centres, or rural hospitals. Since the lockdown, hardly any sterilisation procedures have been conducted in these facilities as they have discontinued these services to focus on the battle against the coronavirus.

Ultimately, an over-reliance on sterilisation and over-dependence on public facilities to provide these services is severely damaging India’s family planning efforts during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. Rather than putting all their eggs in one basket, Indian policymakers would benefit from a more holistic approach that endorses a wider array of contraceptive options. Additionally, there is a need to extend the burden of contraception and family planning to both men and women. This can be achieved by providing targeted education to men and social influencers like religious leaders to promote the concept of family planning. Despite being the first country to introduce a large scale family planning program, the poorly-planned and heavily unbalanced strategy of the existing system has shone a light upon the inadequacies of that program. As the current pandemic exposes the faults of India’s obsession with female sterilisation, will the policy survive this health emergency, or can we expect a monumental change in India’s family planning policy?

Image Source: DNA India