On 1 November 2019, the Government of New Delhi declared a public health emergency owing to a drastic decline in the city’s Air Quality Index (AQI) to near-toxic levels.

One the reasons for high levels of pollution in the city is its geographical location at the head of the Indo-Gangetic plain, as the Himalayas block air movement and creates a mist which traps particles at the ground level.

Nevertheless, in spite of the presence of mitigating environmental factors, policy implementation has largely failed to curb rising air pollution levels.

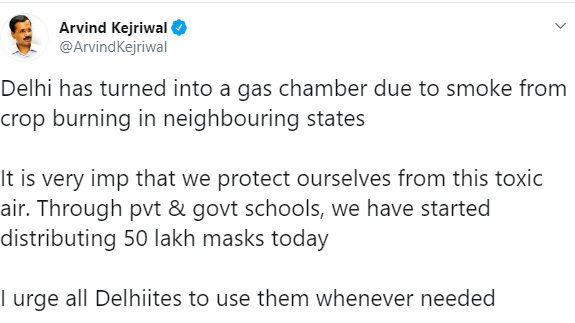

The most obvious reason for this is the political unwillingness to take responsibility for the crisis. This is illustrated in the tweet below by Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, who passed the buck for the disaster on to neighbouring states.

Furthermore, a meeting called by Parliamentary Standing Committee on Urban Development for discussion on air pollution was missed by a majority of Delhi’s political leaders.

One of the few solutions which have been implemented by the Delhi government has been the odd-even rule, under which only even number plate vehicles can travel on even dates, and vice versa. Despite popular support and its effectiveness in curbing pollution, studies argue that the impact of this policy has been negligible, as the contribution of vehicular emissions on the city’s air pollution is debatable.

Simultaneously, there are several structural issues which hinder progress in tackling air pollution.

For example, the principal functions of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), as per Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981 are to abate air and water pollution through prevention and control mechanisms. The CPCB also monitors water and air quality and implements various pollution mitigation programs. However, the body is mandated to monitor the results of its own activities, thereby leading to a conflict of interest that has often led to underreporting.

Concurrently, the Government of India announced the National Biofuel Policy in 2018 to reduce the use of fossil fuels and provide funding for biofuel plants. However, despite the fact that the production of biofuels relies on an abundance of agricultural crops and that agriculture is a state subject, the central government has failed to engender adequate cooperation with states on the implementation of this policy.

Furthermore, the Environment Pollution Control Authority (EPCA) implements a Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP), which places restrictions are put on industrial activities based on the pollution level. However, the majority of these plans are only implemented after the air quality has already deteriorated, as a corrective measure rather than a preventive measure.

Simultaneously, there is grave negligence and misunderstanding of the need for a long-term strategy. For instance, November 16, when the air quality in the NCR had marginally improved, Union Minister Prakash Javadekar announced that industries no longer had to obtain a no-objection certificate (NOC) from the Departments of Pollution, Labor and Industry in the region.

As a result of structural inefficiencies, poor policy implementation, and a lack of understanding of the dangers of air pollution, the Centre for Science and Environment reports that life expectancy in India has reduced by 2.6 years.

In order to prevent the situation from worsening, the region must implement a host of different mitigation approaches. For instance, there must be public service announcements encouraging the use of public transport systems. Concurrently, there must be third-party monitoring and reporting of the CPCB’s activities to ensure accurate reporting of pollution statistics. Simultaneously, the central government must generate greater cooperation with state governments to ensure the diversification of crops and the creation of biofuels as an alternative source of energy.

The region can also borrow successful policies from other cities and states. For instance, various studies have shown that the congestion tax is more effective than the odd-even rule in reducing exhaust emissions. An emission trading scheme has also been successfully trialled in Surat. Under this scheme, the government has set a cap on emissions, and firms that emit pollutants under this limit can sell this gap to firms whose emissions are exceeding these limits, thereby incentivizing industries to use low carbon technologies.

The worsening of air quality in the national capital region after Diwali has become an annual phenomenon with serious and worsening health consequences, and the band-aid solutions of central and state governments have done little to curb the rise in air pollution. There is a need for cooperation amongst all the stakeholders to come up with holistic, long-term solutions to the issue.

Reference List

About Us | CPCB|Central Pollution Control Board. (2019). Retrieved 3 December 2019, from https://cpcb.nic.in/Introduction/

ANI. (2019). Industries won't need NOC from Departments of Pollution, Labour, Industry in Delhi: Javadekar. Retrieved 3 December 2019, from https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/industries-won-t-need-noc-from-departments-of-pollution-labour-industry-in-delhi-javadekar-119111601248_1.html

Greenstone, M., Pande, R., Ryan, N., & Sudarshan, A. (2019). The Surat Emissions Trading Scheme. Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago.

PTI. (2019). Life expectancy in India down by 2.6 years due to air pollution: Study. Retrieved 3 December 2019, from https://www.livemint.com/politics/news/life-expectancy-in-india-down-by-2-6-yrs-due-to-air-pollution-study-1560264853791.html

Image Source: Ars Technica