During his week-long tour of the Middle East last month, Chinese Foreign Minister (FM) Wang Yi visited Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Oman. By the end of the tour, he had secured major deals in the fields of trade, investment, energy, and technology with all the countries. However, the highlight of the Chinese FM’s tour was his trip to Iran. In a move reflective of China’s growing presence in the region, Beijing and Tehran signed a landmark 25-year cooperation deal. While the fine print of the agreement is yet to be made available, China has promised that it will invest $400 billion in Iran’s economy over the agreed period. Furthermore, a New York Times report regarding the specifics of the deal shows that China aims to invest in Iran’s faltering economy in exchange for a “regular and heavily discounted” supply of oil. The deal, as expected, will play an influential role in strengthening China-Iran relations. In spite of the agreement, however, China’s influence in the Middle East remains at an embryonic stage.

Currently, the two main drivers of China’s relations with Iran are energy and connectivity. China relies on the Middle East for almost half of its energy supplies and Iran has been a major contributor to China’s growing demand for oil. However, crippling economic sanctions imposed by the United States (US) on Iran have led to China greatly reducing its oil intake from Iran, especially in 2018 and 2019. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Iranian oil fell to 3% of China’s imports in 2019 from 8% in 2016. The US has also threatened to sanction anyone dealing with Iran and in light of this China has decided to pursue its own energy policy even if it is in violation of the sanctions. As a result of this, it has been reported that China has recently increased its oil imports from Iran, as US sanctions have led the country to offer oil at extremely cheap rates. Admittedly, Beijing does not officially report any direct transactions with Tehran and most of its purchases are labelled as Middle Eastern oil or Malaysian blend. There have also been no official reports on how these increased efforts from Iran to sell its oil have affected its economy in the wake of sanctions. However, it is generally thought that China’s purchase of Iranian oil has rebounded and played a large part in keeping the Islamic Republic’s struggling energy industry afloat.

With regards to connectivity, the deal aims to increase transport and construction projects in Iran while also increasing Chinese presence in sectors like banking, telecommunications, ports, and railways. Iran is situated between Central Asia and the Middle East and is viewed by China as its gateway into the wider region. China has proposed a high-speed rail network between the two countries and in 2016, the first train arrived in Tehran from Yiwu in China. Furthermore, the Chabahar region in Iran could also provide an alternative for Chinese crude oil shipments which have to pass through chokepoints like Suez, Hormuz, and Malacca.

The China-Iran bonhomie is not just a result of Iran’s importance to China as a strategic geopolitical hub but is also based on China’s reliability as a strong partner to Iran. Beijing’s efforts to cement its partnership with Tehran are currently focused on three factors: the 2015 nuclear deal, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and its vaccine diplomacy.

China played a crucial role in finalising the 2015 nuclear deal, officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which was signed between Iran and world powers. The signing of the deal provided Tehran with crucial sanctions relief in return for it scaling back its nuclear programme. However, the JCPOA came crashing down in 2018, when the US administration led by then-President Donald Trump decided to unilaterally exit the deal and re-impose sanctions. This negatively affected China’s efforts to seek new avenues of cooperation with Iran, as the US threatened to impose sanctions on anyone doing business with Iran. With the new US President Joe Biden signalling an interest in re-joining the nuclear deal, China is once again playing an active role in reviving the deal through its involvement in the Vienna talks between world powers on reviving the JCPOA.

Parallel to these efforts, China is also seeking to expand its BRI, which it hopes will give it the status of a global powerbroker by spreading its influence to Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Since Iran lies at the strategic juncture between Central Asia and the Middle East, any infrastructure project trying to connect the two regions must include Iran in its plans. Realising this, Tehran has cosied up to Beijing in the hopes that this will lead to more investment in the country’s struggling economy.

Another important aspect of China’s ties with Iran has been its COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy. Iran has already received 250,000 doses of China’s Sinopharm vaccines, which has been greatly appreciated by a country that has recorded over two million cases and more than 67,000 deaths from the virus. The ongoing pandemic has crippled Iran’s already stagnating and heavily sanctioned economy, in light of which Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy has accelerated the country’s economic recovery and boosted its weak public health response.

Moreover, if the ongoing talks in Vienna, aimed at reviving the nuclear deal, are successful and result in sanctions on Iran being lifted, China will not only be able to position itself as a key power and stakeholder in Iran but across the region at large. At the Vienna talks, Chinese representative Wang Qun called for the removal of the US’ “illicit sanctions” against Iran and said the US should stop its “long-arm jurisdiction” targeting anyone who does business with Iran. His statements clearly illustrated the adverse impacts of the US-Iran conflict on Chinese interests and its motive for seeking to play a role in brokering a new deal between the US and Iran. To this end, in last month’s explosive US-China meet in Alaska, the Chinese delegation called on the US to take practical steps with respect to reviving the JCPOA, while reiterating their commitment to "play a constructive role" in renegotiating the deal. Chinese officials have also been meeting directly with the Iranian delegation on the sidelines of the Vienna talks and have firmly stood by Iran.

Similarly, its BRI projects could draw interest from other Middle Eastern countries, as they have done in Latin America and Africa. To this end, China’s vaccine diplomacy may allay fears of the debt-trap diplomacy of its BRI by projecting an image of a benevolent superpower. In fact, it has already delivered vaccines to Algeria, Egypt, Turkey, Bahrain, UAE, and Jordan; UAE has even signed a deal that allows it to locally produce the Sinopharm vaccine.

Regardless of China’s expanding footprint in the Middle East, though, it still remains some way off from challenging American primacy in the region. However, some experts have suggested that this paradigm could be shifting. The previous Trump administration took several steps that reduced US influence in the Middle East, including the removal of troops stationed in Syria alongside Kurdish military units, stopping aid to Palestine, and unilaterally exiting the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran. Although Biden has since restored aid to Palestine, he has also announced the full withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan.

In light of these developments, China has already made efforts to fill any vacuum left by the US and even attempt to match its efforts in some instances, as evidenced by the fact that China has expressed interest in mediating the Israel-Palestine conflict by agreeing to host leaders from both sides.

Srikanth Kondapalli, a professor in Chinese studies at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, told Statecraft that due to the “gradual withdrawal” of US troops from the region, China’s outreach in the Middle East has increased. This has a lot to do with America’s ‘Shale Revolution’, which has allowed the US to diversify its energy needs and reduce its dependency on the Middle East for oil. That being said, Kondapalli also added a caveat that the US withdrawal does not mean a decline of its strategic foothold in the region and does not give China any major advantage over the US.

The US’ policy in the Middle East is a result of decades of diplomatic and military efforts. Diplomatically, US successes in the region include the 1978 Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel, the 1993 Oslo Accords between Israel and Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), and the 2020 Abraham Accords, which saw UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco sign peace deals with Israel. Militarily, the US has been involved in almost every war in the region, either as a direct participant or as a negotiator. The US is also a major supplier of arms to most countries in the Middle East, including Israel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar.

Kondapalli noted that China has also set up an “arms bazaar” in the Middle East, with countries like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and UAE now buying arms from China in order to diversify their purchases. However, regardless of these developing efforts, China still has a long road ahead if it hopes to catch up with the US firepower in the region. SIPRI, in its report on Global arms transfers from 2016 to 2020, recorded that 47% of the total US arms exports went to the Middle East. Considering that the US continues to account for 37% of global arms exports, compared to China’s 5.2%, it is unlikely that there will be any market shift on this front anytime in the near future.

Moreover, China’s efforts in the Middle East could also be undercut its apparent persecution of Uyghurs, a largely Muslim minority in its Xinjiang province. For instance, Turkey, which has the largest Uyghur diaspora in the world, recently summoned the Chinese ambassador in response to the Chinese official’s harsh criticism of Turkish opposition party members for expressing support for the Uyghur cause. Turkey has also seen numerous protests against Chinese actions in Xinjiang. There also remain underlying trust issues surrounding its BRI, especially with regards to its potential debt-trap diplomacy.

Regardless of these teething issues, however, China is firmly on the path to cementing a presence in the Middle East, with Iran acting as its main lynchpin into the region. In a recently conducted survey in Iran, a majority of 53% Iranians said that China today is “more respected than ten years ago.” While this figure might not in and of itself indicate that China could eventually match US influence in the region, it definitely signals progress and indicates China’s evolving efforts to emerge as a major player in the Middle East, irrespective of a decline in American primacy.

Are China’s Ties With Iran an Indication of its Growing Clout in the Middle East?

China's increased push for greater influence in the Middle East has been met with both challenges and opportunities.

April 22, 2021

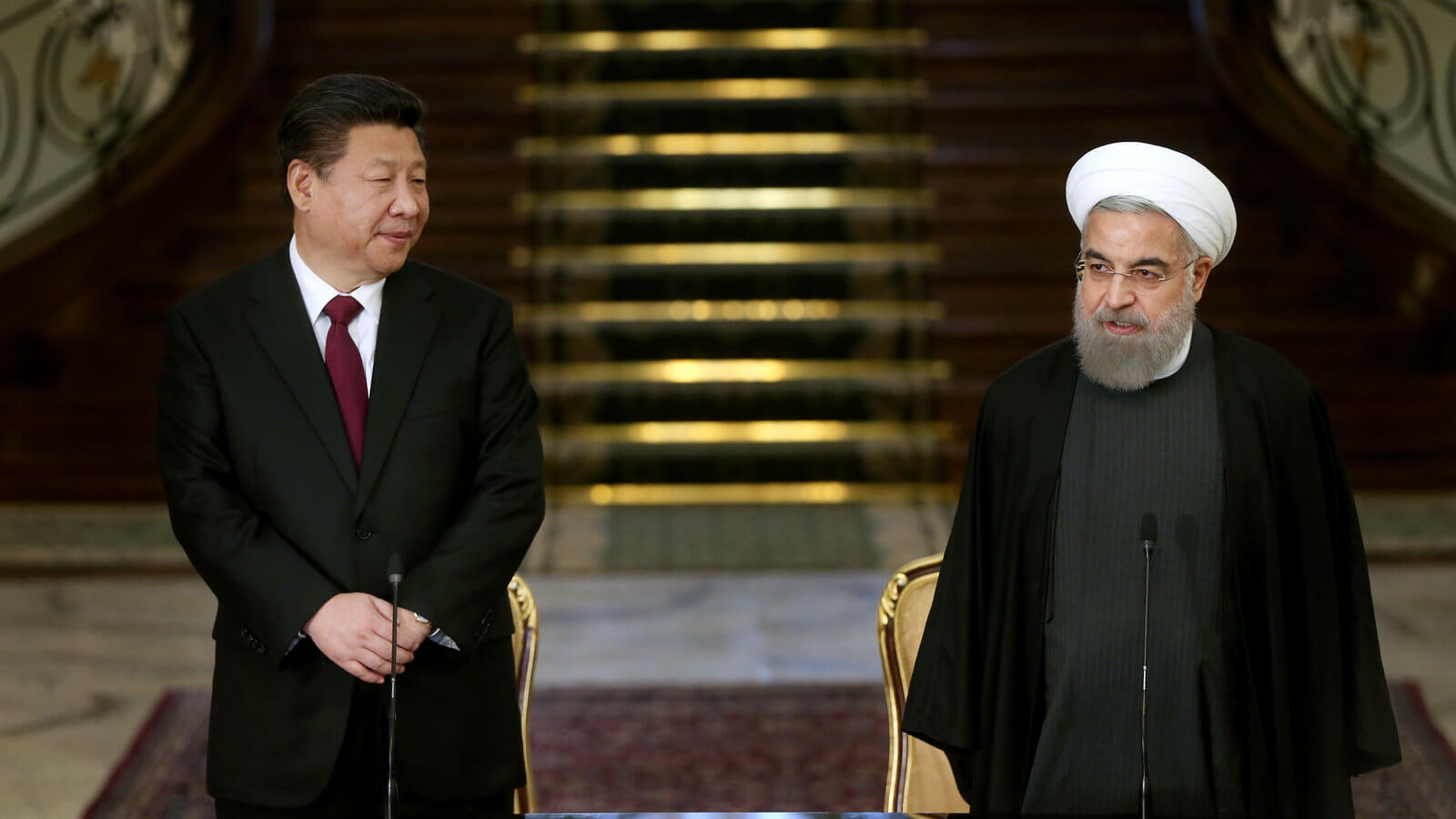

Chinese President Xi Jinping with his Iranian counterpart Hassan Rouhani SOURCE: EBRAHIM NOROOZI/ASSOCIATED PRESS